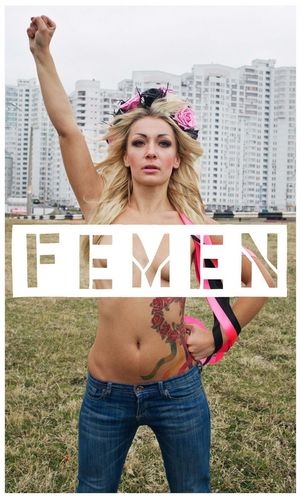

Bare-breasted and crowned with flowers, perched on their high heels, Femen transform their bodies into instruments of political expression through slogans and drawings flaunted on their skin. Humour, drama, courage and shock tactics are their weapons.

Since 2008, this 'gang of four' – Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna – has been developing a spectacular, radical, new feminism. First in Ukraine and then around the world, they are struggling to obtain better conditions for women, but they also fight poverty, discrimination, dictatorships and the dictates of religion. These women scale church steeples and climb into embassies, burst into television studios and invade polling stations. Some of them have served time in jail, been prosecuted for ‘hooliganism’ in their home country and are banned from living in other states. But thanks to extraordinary media coverage, the movement is gaining imitators and supporters in France, Germany, Brazil and elsewhere.

Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna have an extraordinary story and here they tell it in their own words, and at the same time express their hopes and ambitions for women throughout the world.

Femen is a feminist protest group which was founded in Ukraine in 2008 by Anna Hutso, Oksana Shachko, Alexandra Shevchenko and Inna Shevchenko, who are among its key members. They have attracted worldwide attention for a series of high-profile protests at key international events and currently live in exile in France.

'Ukraine is not a brothel!' This was the first cry of rage uttered by Femen during Euro 2012. Bare-breasted and crowned with flowers, perched on their high heels, Femen transform their bodies into instruments of political expression through slogans and drawings flaunted on their skin. Humour, drama, courage and shock tactics are their weapons. Since 2008, this 'gang of four' Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna has been developing a spectacular, radical, new feminism. First in Ukraine and then around the world, they are struggling to obtain better conditions for women, but they also fight poverty, discrimination, dictatorships and the dictates of religion. These women scale church steeples and climb into embassies, burst into television studios and invade polling stations. Some of them have served time in jail, been prosecuted for hooliganism in their home country and are banned from living in other states. But thanks to extraordinary media coverage, the movement is gaining imitators and supporters in France, Germany, Brazil and elsewhere. Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna have an extraordinary story and here they tell it in their own words, and at the same time express their hopes and ambitions for women throughout the world.

Femen is a feminist protest group which was founded in Ukraine in 2008 by Anna Hutso, Oksana Shachko, Alexandra Shevchenko and Inna Shevchenko, who are among its key members. They have attracted worldwide attention for a series of high-profile protests at key international events and currently live in exile in France.

Manifesto vii

A Movement of Free Women: Preface by Galia

Ackerman xiii

Part I: The Gang of Four

1. Inna, a Quiet Hooligan 3

2. Anna, the Instigator 13

3. Sasha, the Shy One 24

4. Oksana, the Iconoclast 34

Part II: Action

5. 'Ukraine Is Not a Brothel' 43

6. No More Nice Quiet Protests 68

7. Femen Goes All Out 89

8. In Belarus: A Dramatic Experience 105

9. Femen Gets Radical 117

10. 'I'm Stealing Putin's Vote!' 122

11. Naked Rather Than in a Niqab! 128

12. Femen France 150

13. Our Dreams, Our Ideals, Our Men 161

One Year Later: Afterword by Galia Ackerman 168

Notes 182

"Femen and Everyday Sexism are two breakthrough movements to emerge

in recent times, and they bring their own distinct 'manifestos' in

book form. Both confirm that feminism is no longer a dirty word

among twentysomethings but also that the ideology manifests itself

differently from their campaigning Second Wave predecessors."

The Independent

"With Femen, we are dealing with something new ... Its activists

are charting a new route for public discourse about women and

religion, and making it an unabashedly universal discourse,

venturing into realms where they may be hated, and they may yet pay

a high price for this. But that they have gotten people talking,

even shouting and crying, is undeniable, and it is good; only

through debate and discussion, sometimes painful, often unsettling,

will we progress."

The Atlantic

"Femen's aims are straightforward, broad and radical. A war

on patriarchy on three fronts, calling for an end to all religions,

dictatorship and the sex industry."

The Guardian

"Part manifesto part biography this is Ukranian protest

group FEMEN in their own words. Currently exiles in France, the

four key members outline their objectives and sextremist tactics. A

timely look at their 'non-violent but highly aggressive' topless

brand of feminist activism."

Diva Magazine

"This account will inspire activists and inform scholars

for generations."

Publishers Weekly

1

INNA, A QUIET HOOLIGAN

I was born in a ‘godforsaken hole’ in southern Ukraine, in other words in a small provincial town, Kherson. They speak Russian there, like in Odessa, which isn’t very far away. It’s still a very Soviet town, where the USSR still seems to be in existence and nothing ever changes. It was in this quiet town, that’s infuriated me ever since my childhood, that I very soon started to tell myself I’d make a life for myself elsewhere.

When I was a little girl my only friends were boys, and I loved climbing trees. I dressed in shorts and sneakers; I hated dresses. This made Mom furious: she really didn’t like the fact I wasn’t like a model little girl. I didn’t even refuse to wear dresses, but Mom just knew I’d immediately get them dirty and tear them, either by climbing an oak tree or playing with stones on a construction site. Near our apartment block, there was one such site and in the evening, when the workers left, our little gang invaded it and built castles out of the bricks. I needed freedom, and instead of playing with dolls or messing about in a sandbox, I preferred to join the boys on more out-of-the-way expeditions. I didn’t want to be a boy, but I liked having them round me. I was a kind of quiet hooligan, who never took part in fights. The only person I quarrelled with from time to time was my older sister.

Apart from that, I was a well-behaved child. My parents never gave me a spanking. In fact, I’m lucky to have a very nice family. I’d define my mother as an ‘ideal woman’ for Ukraine. She was a chef in a restaurant before becoming chef in a university cafeteria. She’s a typical Ukrainian woman who works full time but also keeps her house spotless, cooks, and takes care of her husband and children without losing her temper or, more precisely, without ever showing her emotions – a nice, quiet, positive and very pleasant woman. But she’s not a fulfilled woman, even if she doesn’t complain about anything. She bears her fate, like a donkey carries its load, without realizing she could have had a different life. I suffered for her. In those days, I didn’t know the word ‘feminism’, but I thought this life was unfair. And the fact it was the norm was no consolation to me. I realized early on that I never would live like her. On the other hand, my sister, who’s five years older than me, completely internalized this model. In fact, she married at nineteen, had a child at twenty-one, and lives and works in Kherson. However, we’ve remained very close, and she’s always supported me.

Dad is a very emotional man, sometimes short-tempered, but he has a good heart too. In the family, we never had any real arguments. With his sense of humour, my father’s always turned any conflict into a mere joke. Our parents argued with my sister and me, without it ever turning nasty.

Dad’s a retired soldier, a former major in the troops of the Ministry of the Interior. I’ll never be able to imagine him without his uniform. During our childhood, when our parents went out, my sister and I would take turns to dress up in Dad’s uniform, but we never had any desire to try on Mom’s dresses or high heels. And when he got promoted, we’d make a hole in his epaulette to screw in a new star. For us, it was a sacred ritual!

If I got good grades in school and worked hard, this was also thanks to my father. He always talked to me as if I was a grown-up and kept telling me I was studying for myself, for my future. When I started at primary school, he told me that my adult life was about to begin. I quickly realized that there was a hierarchy at school: some children are better liked by the teachers, who straightaway help them and stimulate them. It’s a virtuous circle: if you work hard, you’re appreciated by the teachers, and they push you to develop your abilities and become even better. From the first year, I wanted to be the class representative. And I conducted the first electoral campaign of my life. I was elected by a show of hands. In fact, the role gave me a serious responsibility because it meant keeping a register of late arrivals and absences, organizing and lining up the pupils for outings and so on. I held this position throughout my time at school, up until my final exams.

Around the age of twelve, I went through a bit of a crisis. I suddenly realized that the boys preferred girls with dresses and pretty little shoes. As I wanted to be first in everything, I started to dress in a more feminine way and I grew my hair down to my waist. The effect was instantaneous: a lot of boys fell in love with me, including some of my friends. There were plenty of girls who wanted to be my friend because I was the leader of the class, but I thought they were airheaded chatterboxes and I kept my distance. I’d just one girlfriend who was also an excellent pupil. We shared the same table and with her I felt comfortable. In my class, out of twenty-two pupils, there were only seven boys. With my one girlfriend and these boys, we formed a separate group, away from the other girls.

When I was about fourteen, I developed a new ambition: I got it into my head that I’d become president of the school. For us, this was an important function, much more than being just class representative. The school president attends school board meetings and voices the wishes and grievances of the pupils. He or she also organizes competitions and festivals – an important personage, in short. And then the title itself is rather flashy: president! In theory, you can take on this post when you’re in the fifth year of secondary school but, in general, pupils vote for people who are in their final year. So my chances of being elected in the fifth year were almost zero. Still, I decided to stand against the nine other candidates. We campaigned for three weeks. We handed out leaflets and each made two public presentations of our platforms. These presentations took place in the main hall where candidates had to go on stage and try to convince the audience. Almost all the pupils took part in the elections, we all wanted to play at democracy, that game for adults. In each class there were ballot papers and boxes. The count was conducted by teachers and pupils drawn by lot.

The day after the election, our class was on duty to maintain order in the school. As class representative, I had specific obligations: I had to place pupils at monitoring stations in the canteen, the schoolyard and so on. Just then, the headmistress ran up and whispered in my ear that I’d won. It turned out that I’d won the majority of votes in thirteen classes out of fifteen – it was an outright victory! That was how my career as president started, and I was re-elected twice, in the last two years at school. This was my first ‘political’ experience, an unforgettable one, the start of which coincided with the 2004 presidential campaign.

The two main presidential candidates in Ukraine were Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych, who was backed by the outgoing President, Leonid Kuchma. Back in Kherson, everyone supported Yanukovych, both my family at home and the teachers at school. And then pressure was put on us too. For example, Mom told us that, at her workplace, officials in the local government had threatened to fire anyone who voted for Yushchenko. I tried to explain to my mother that this was bollocks, but she was scared. In eastern Ukraine, most people were aware that Yanukovych wasn’t a good candidate, but, out of fear of retaliation or indifference, many were ready to vote for him in spite of everything.

I remember propagandists from the Donbas, the stronghold of Yanukovych, claiming, ‘He’s a local lad, he went to prison, like so many other people, for snatching hats.’1 This kind of activity is usually carried out by small-time thugs who snatch the hats off people’s heads and only give them back if they’re given a few coins in exchange. That said, metaphorically speaking, this is how the majority of Ukrainians live – committing petty crimes to survive when they’re living in poverty. So it was a clever propaganda technique to present Yanukovych as a man of the people challenging the intellectual Yushchenko, the candidate of the Ukrainian-speaking elite and married to an American. The Yushchenko couple also spoke Ukrainian at home, and their children wore traditional costumes, shirts with embroidered collars, which was both incredible and intolerable for people in eastern and southern Ukraine. Indeed, the Soviet propaganda that supported Yanukovych presented Ukrainian nationalism as a kind of backwardness. To have a career, you absolutely had to be Russian-speaking.

At the same time, people wanted change, and all Yanukovych could offer was a continuation of the crooked Kuchma regime. A new man, a new background, a new face, but the same words, whereas the ‘extra-terrestrial’ Yushchenko had something really original and interesting to say. He called on Ukraine to foster links with Europe and the West and to escape from the Russian yoke, and his appeals carried home. Then there was the story about Yushchenko being poisoned with dioxin during the campaign – we still don’t know who was behind it: it led to a wave of sympathy for him. The election campaign was very eventful. Even though I was too young to vote, I understood that Yanukovych could represent neither the interests of the country nor mine. For me, this former petty criminal who...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.6.2014 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Andrew Brown |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Allgemeine Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Activism, feminism, protests • FEMEN • Feminismus • Feministische Theorien • feminist theory • Gesellschaftliche Bewegungen, Bürgerbewegungen • Gesellschaftliche Bewegungen, Bürgerbewegungen • Political Science • Politics & the Media • Politik u. Medien • Politikwissenschaft • Social Movements / Activism • Sociology • Soziologie |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7456-8325-8 / 0745683258 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7456-8325-6 / 9780745683256 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich