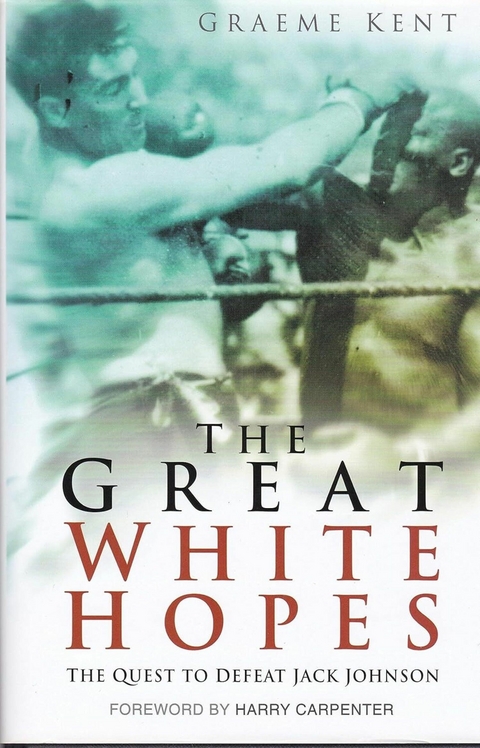

The Great White Hopes (eBook)

256 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-9615-3 (ISBN)

1

‘THERE WAS NO FIGHT!’

It was several minutes past midday on the afternoon of 26 December 1908. The first World Heavyweight Championship under the Marquess of Queensberry rules between a white and a black boxer was about to end. In the fourteenth round, Tommy Burns, the totally outclassed Canadian heavyweight champion of the world, had been smashed to the canvas for a count of eight. As the fighter staggered to his feet, bleeding from the nose and mouth, Superintendent Mitchell, in charge of the 250-strong police contingent at the ringside in the open-air stadium at Rushcutters Bay, just outside Sydney in Australia, climbed into the ring.

Unable to make himself heard above the noise of the crowd, the inspector indicated to the referee, Hugh D. McIntosh, who was also the promoter of the contest, that he should stop the fight. McIntosh nodded and moved forward to do so. Ignoring him, Jack Johnson, the black American challenger, advanced to finish off the reeling Burns.

Sam Fitzpatrick, Johnson’s manager, and his seconds, terrified that their man would be disqualified, screamed at Johnson to step back. Their cries rose to the cloudless skies; unable to borrow enough wood to complete the stadium, McIntosh had built it without a roof. The black heavyweight saw his handlers’ wild gesticulations and hesitated. McIntosh shouted, ‘Stop, Johnson!’, and placed his hand on the black man’s shoulder as an indication that he was the winner and new champion.

Realising what was happening, Tommy Burns turned on Superintendent Mitchell, who had instigated the stoppage, and swore luridly at him, demanding that he be allowed to fight on. Pat O’Keefe, a British middleweight boxer and Burns’s chief second, hurried across the ring and led the still shouting and struggling former champion back to his corner. Burns was $30,000 richer, the highest sum ever paid to a boxer up to that time, compared to Johnson’s $5,000, but his championship had passed out of his hands.

Towards the end of his life the Canadian would always deny vehemently that he had been outclassed by Johnson. He claimed that the police had intervened mainly because Rudy Unholtz, a Germanborn South African boxer on Johnson’s payroll, had crept under the elevated ring as early as the tenth round. From here, Burns declared indignantly, Unholtz had kept screaming, ‘Stop the fight!’, thus influencing the police at ringside. Few spectators backed Burns’s claim.

In the immediate aftermath of the Rushcutters Bay championship bout, Burns stayed on in Australia and lost much of his purse money at the races. He took his losses philosophically. A shrewd businessman but a pragmatist, he had been paid one dollar and twenty-five cents for his first fight, against Fred Thornton in Detroit in 1900, and he had once journeyed all the way to the Yukon to inspect a gold mine he had won in a poker game. Finding it to be worthless, he had earned his passage back by fighting the local champion, Klondike Mike Mahoney.

For some time Johnson had been pursuing Burns halfway across the world in search of a title shot. Over a nine-year period, he had defeated all the major black contenders and those white heavyweights who would fight him, and now he was 30. He had scraped a living across the USA, working as a sponge fisherman, stable boy, porter, dock labourer and sparring partner. He had ridden the rails as an itinerant wanderer and lived and fought in hobo jungles. Before he had been lucky enough to embark upon an organised boxing career, he had taken part in the horrific ‘Battles Royal’, where half a dozen or more black youths were pitched into a ring at the same time and forced to fight for the delectation of a largely white audience until only one was left standing. It was the right sort of background to produce a tough, bitter and fearless man.

After years in the doldrums, boxing was undergoing a worldwide resurgence, although there was little legislation anywhere to control the sport. There were no national controlling bodies and there was little organisation, just fights everywhere before huge crowds. Even President Theodore Roosevelt in the White House had his own resident fisticuffs trainer in ‘Professor’ Mike Donovan, a grizzled former bare-knuckle fighter and veteran of General Sherman’s Civil War march through Georgia.

Taking advantage of the general enthusiasm for boxing, Johnson decided temporarily to remain in Australia, though definitely not in Sydney. A goodwill visit by a fleet of sixteen US battleships, which had occurred before the title fight, had aroused alarm and anti-black resentment in the city. Many citizens feared that the warships would be crewed almost exclusively by black seamen, who might not take kindly to the prevailing ‘White Australia’ policy. This had caused The Age, a Melbourne newspaper, to state reassuringly, ‘It is not at all probable, however, that a very large proportion of the crews will be found to be coloured. There will be some on the battleships, but they will not be nearly as numerous as rumour is suggesting just now.’

Hugh D. McIntosh had relied on sailors from the fleet to support the Burns–Johnson contest. In fact the Americans showed very little interest in the bout, causing the promoter to remark, possibly with some exaggeration, ‘Australians supported it. I had counted on American sailors for a possible sellout. Exactly two appeared in uniform. They started fighting and had to be evicted.’

Before the fleet had left to sail home, the Australian Defence Minister, Mr Ewing, had urged the departing Americans to tell their fellow-countrymen that they had seen for themselves that Australia was emphatically a white-man’s country and would remain so.

The ‘White Australia’ policy had been sparked off in the 1850s to combat the influx of over 50,000 Chinese immigrants who came to join in the gold rushes. Not only were the new labourers distinctive in their appearance, maintaining their own social customs, they toiled hard and cheaply. Soon they became very unpopular with Australian workers in the goldfields. By 1888, legislation had banned any more Chinese from entering the country. It was not long before the policy was applied tacitly to all non-whites. This was emphasised in 1903, when a trading vessel was wrecked off the coast at Point Nepean. The survivors were taken to Melbourne by a rescuing tugboat, but only the white officers and crew-members were allowed ashore. The non-whites were put on a Japanese mail ship and conducted to Hong Kong. Within another five years, by the time that Burns fought Johnson, most of the South Sea Islanders who had been recruited in the nineteenth century to work in the cane fields of the north had been sent back home.

So how did a black boxer become heavyweight champion of the world on Australian soil? White Australians loved their sport and were becoming increasingly good at it. The English cricket team which had toured the continent in 1907/08 had lost four of the five games it had played against the Australians, while at the 1908 Olympics the Wallabies had defeated England, the only other entrant for rugby football, 32–3.

In addition, boxing was immensely popular in Australia, and in Squires and Lang the country had just produced a pair of formidable heavyweight boxers of its own. So highly were these two regarded by their fellow-countrymen that the world’s leading big men, Jack Johnson and Tommy Burns, had been imported in the hope that the favoured home-grown boxers would defeat them. Unfortunately, both Australians had been crushed by Burns, while Johnson had compounded the national disappointment by thrashing Lang. These impressive results had led to a public outcry for Burns to defend his title against the black challenger, and Johnson had been allowed to return to meet him.

The black fighter’s subsequent victory was a watershed in the history of sport. For the first time, boxing left the sports pages and was featured all over the world in major news stories on the front pages of the contemporary tabloids and broadsheets alike. Typical was the New York Evening Journal, which published a picture of Johnson occupying most of the front page, unprecedented coverage for a sporting personality. Caucasian supremacy had been publicly challenged and humiliated. The fact that the breakthrough had occurred in the haphazard and often crooked world of professional boxing made matters even worse. What, people wondered, appalled, would happen to the established order with the scarcely known and unpredictable ogre Jack Johnson now bestriding the sport like a colossus, a figurehead for his oppressed race?

In the immediate aftermath of his victory the new champion felt that, under the circumstances, he would be more popular on a tour of the remoter areas of Australia than he would in the large cities. He cashed in on his new title by touring Western Australia, fighting exhibition contests and making public appearances. In the outback, with his outgoing personality, gold teeth, shaven head and colourful ring attire, he was a great success. By the end of his short small-hall tour of the Antipodes, he had almost doubled the money he had been paid for fighting Burns. If he had been self-confident before, Johnson was now positively ebullient.

An example of his strong self-worth and refusal to buckle under white pressure occurred in the gold-mining town of Kalgoorlie, when he stopped for a drink in the Palace Hotel. While he was there, one of his many new-found instant friends admired Johnson’s superb defensive qualities but remarked that it would...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.3.2005 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Harry Carpenter |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Kampfsport / Selbstverteidigung | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Boxer • Boxers • Boxing • civic unrest • Fighter • Fighters • Fights • heavyweight champion of the world • heavyweight world championship • race riots • The Quest to Defeat Jack Johnson • The Quest to Defeat Jack Johnson, heavyweight world championship, heavyweight champion of the world, civic unrest, race riots, boxing, boxers, boxer, fighter, fights, fighters |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-9615-8 / 0752496158 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-9615-3 / 9780752496153 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich