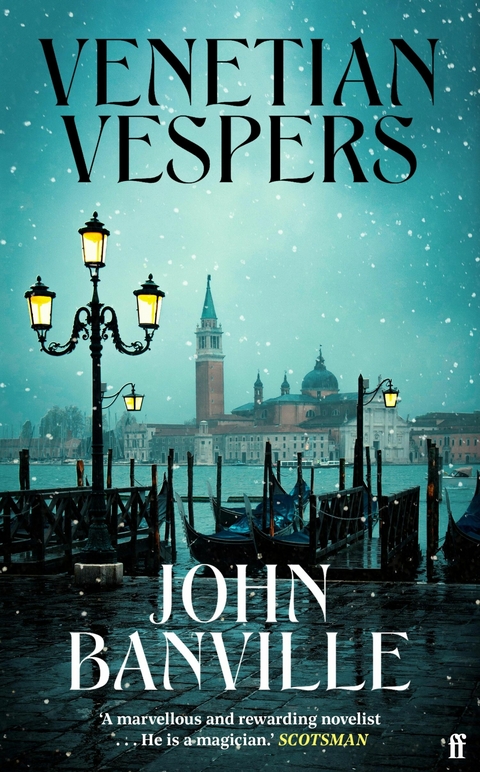

Venetian Vespers (eBook)

368 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-38665-9 (ISBN)

JOHN BANVILLE was born in Wexford, Ireland, in 1945. He is the author of many novels, including The Book of Evidence, the 2005 Booker Prize-winning The Sea, and, more recently, the bestselling Strafford and Quirke crime series, which has twice been shortlisted for the CWA Historical Dagger.

A SUNDAY TIMES AND TLS BOOK OF THE YEAR, SHORTLISTED FOR THE AN POST IRISH BOOK AWARDS 2025FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF SNOW AND THE SEAEverything was a puzzle, everything a trap set to mystify and hinder me. . . Winter 1899, and strange things are afoot. As the new century approaches, English hack writer Evelyn Dolman marries Laura Rensselaer, the daughter of a wealthy American plutocrat. But in the midst of a rift between Laura and her father, Evelyn's plans for a substantial inheritance look to be dashed. Arriving in Venice for their belated honeymoon at Palazzo Dioscuri - the ancestral home of the charming but treacherous Count Barbarigo - the couple are met by a series of seeminglyotherworldly occurrences, which exacerbate Evelyn's already frayed nerves. Is it just the sea mist blanketing the floating city, or is he really losing his mind?'A marvellous and rewarding novelist . . . He is a magician, really.' THE SCOTSMAN'Banville has a grim gift of seeing people's souls.' DON DeLILLO'The most eminent innovator in Irish fiction of the last 50 years.' IRISH TIMES'One of my favourite writers alive.' REBECCA F. KUANG'Banville writes prose of such luscious elegance.' NEW YORK TIMES

Dusk, a deserted room, a scrap of black silk on a marble table, darkening waters beyond. This was the scene, unpeopled, dim and silent, that I had been dreaming of for months, often on two or three consecutive nights, always the same dream, the same tableau, more or less, more than less. What did it mean, what did it signify? I did not know, could not guess, and the enigma of it troubled me almost as much as did the dream itself. I thought it must be to do in some way with Venice, since it was in Venice that my wife and I were to pass the first months of the new year—and of the new century, as it happened—and naturally I was much preoccupied with that mysterious, not to say phantasmal, city set, impossibly, in the midst of a swamp.

The most remarkable aspect of the dream, aside from its repetitiveness, was that the few objects that appeared in it—the table, the handful of crumpled fabric, the window giving onto what I knew must be the lagoon—all appeared somehow familiar to me, so much so that when I started awake in bafflement and distress, with a dry mouth and in a tangle of damp bed sheets, I was convinced that the room in the dream was a room in Venice that I had visited, and had more than visited, had lodged in. Yet how could that be, since I did not know the city, had never been there?

But then, I told myself, trying to make sense of it, is that not the case with all of the places, things, and people we dream of, that they seem mundanely familiar and at the same time inexpressibly strange?

Dolman is the name, Evelyn Dolman. I am by trade a man of letters. You might have heard of me in my day, for I had a middling reputation in the period coming to be known, in our increasingly Frenchified age, as the fin de siècle, that is, the 1890s. I choose the word “trade” deliberately. I wrote books, stories, plays, and much journalism besides, with the simple and express purpose of establishing a reputation in the world and making a living from it. If I was successful, however moderately, it wasn’t through inspiration—whatever that may be—but by dint of rigid application and dedicated labour. My models were the likes of Henry Mayhew, Bernard Shaw, and, of course, H. G. Wells, whom I met once, or at least bumped into, at the offices of some publisher or other.

I took pride in my work. It was solidly and cleanly done, and polished to the best of my ability. My aim was to entertain the reader and, when the opportunity presented itself, to enliven his mind and improve his character. Also—

Oh, stop. I sound like Uriah Heep. More, I sound like Uriah Heep’s creator. That’s not me. My moderate aims, my craftsman’s pride—pah!

The fact is, I set out to be a lord of language who in time would be placed among the immortals. Mayhew? A midget. Shaw? Pshaw! And as for that whoremaster Wells, don’t get me started. No, my targets were the mighty beasts of the literary jungle, the Henry Jameses, the George Eliots, the Conrads and the Hardys and the Ford Madox Fords. Not to mention the Flauberts and the Tolstoys. Not to mention the Shakespeares! There was no giant whose mighty shoulders my ambition would not o’ervault, no polished pard whose eye my pen, that steely poignard, would not pierce. What was it poor half-mad Kleist said to the great Goethe? I shall tear the laurel wreath from thy brow! Well, there would be a forest of wreathless brows before Dolman was done. I would outwrite them all!

Aye, and look what I became: a Grub Street hack.

Let me list my triumphs. The money-spinner was my Layman’s Guides to the cathedral cities of the south of England, which somewhat to my surprise were warmly received when they appeared annually in a series throughout the 1890s. These handy little volumes continue to sell, in a small way. I notice that my publisher, spineless weasel that he is, has silently removed my name from the title page of the latest reprints. So now I’m one with old Farringdon, my tame antiquarian, whose vast knowledge of rood screens and rose windows and the rest I drew on extensively in the Guides, without, I regret to say, thanks or attribution. Book reviews, short stories, essays on topical issues were taken by all the popular magazines, such as Punch and the Strand. National newspapers regularly commissioned pieces from me, not always of a lightweight nature. There was talk briefly of my being sent to the Cape Colony to report on the warlike intentions of the Boer, but I thought it prudent not to expose my person to the Anglophobia of those trigger-happy settlers, especially as the commissioning paper was the Sheffield Evening Herald, and the fee would have been commensurate with its provinciality and its modest circulation figures.

Then there was my novel, Poor Souls, written—no, seared onto the page—in a five-week transport of righteous fury at the wretchedness of the lives of London’s indigent classes. The manuscript did a fruitless round of the publishing houses for the best part of a year. In the end I brought it out at my own expense, and was cheated in the process by a rascally printer with premises in Fetter Lane, which subsequently, to my deep satisfaction, burnt to the ground in a conflagration so intense that it melted most of the printing press. The book attracted a single notice, in the Aberystwyth Observer, whose semi-literate reviewer described me as a faux-Fourierist—I looked up this Fourier, and failed to see what my polemic had to do with higher mathematics—and laughed at my “half-baked social theories” and “emetic flights of sentimental gush.”

My work, then, was—

But why do I persist in speaking in the past tense? Am I not still here, am I not scribbling still? Look at this nib, moving across the page, with a tiny secret sound all of its own, setting line upon line upon line. Yet I feel that, like the poet Keats, I am leading a posthumous existence, and that already I have made my final and inevitable awkward bow. What happened? Upon what rock did all my plans and grand ambitions founder? The trouble is, it seems, I never got started properly. Ever the vacillator. I think upon that eager tyro I once was and grieve for him and all he might have done; I grieve as I would for a marvellously talented brother, say, another Keats who died disgracefully young.

Given all these disappointed hopes and aims, all this dismal having to make do, you can easily imagine what a shock, nay, what an outrage, it was to find myself at the centre of the dark and tragic events which took place in the first weeks of that winter and which afterwards were the subject of so much prurient and hysterical attention in the public prints—I almost wrote “that fateful winter,” but, recalling the jeers of a certain Mr. Jones of Aberystwyth, I am henceforth determined to eschew the all too easy clichés which I confess I was prone to employ in the past. It’s true, a woman died, but through no fault of mine, on that I shall continue to insist while I still have breath in my body. Of course, I was portrayed as an out and out blackguard, the lowest of the low, but now I mean to have my say and put on record the truth of what occurred in those strange days at the start of the century. And I trust that my version of this desperate affair will be accepted at face value, and not mistaken for the greenery-yallery ravings of some aesthetical absinthe-imbibing décadent of the kind whose vapourings used to be found splattered across the pages of such degenerate and now happily defunct journals as The Yellow Book and The Savoy. Oh, yes—see me rubbing my hands, see my vengeful grin. When one has been through hell, the burnt flesh burns on.

Before embarking properly on my sombre tale, before land is out of sight, so to speak, I should give some small account of myself as I was, or perhaps I should say as I conceived myself to be, in those days. An Englishman, certainly, of the dark-haired, stocky type, broad-shouldered, with a brow neither high nor low; upright in carriage, brisk in action, and, above everything, straight: straight of glance, straight of speech, straight of demeanour. No Beardsley I, no, nor Wilde, either—the deuce no! I dressed not ostentatiously but with taste and refinement, and was as heedful of my boots as of my linen. Some who knew me might say I was aloof, even a touch arrogant, and it’s true that although my origins were far from aristocratic, I considered myself as fit as any member of the Athenaeum or the Jockey Club to parade the pavements of St. James’s Street or disport myself on the grands boulevards of Paris. And, I would have demanded, why not? Is there not an aristocracy of spirit that transcends the humble status of one’s antecedents?

So there you have me, as I was then, a stiff-necked, self-regarding booby, prinked and pomaded, in bowler hat, bow tie, mustard checks, and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.9.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-38665-2 / 0571386652 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-38665-9 / 9780571386659 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich