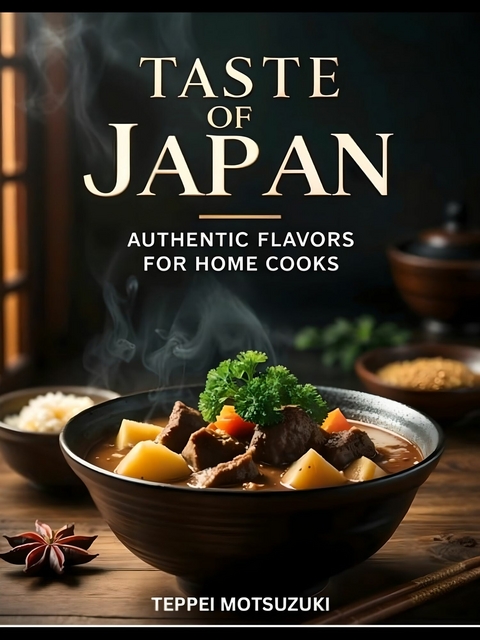

Taste of Japan (eBook)

131 Seiten

Seahorse Pub (Verlag)

978-0-00-095624-8 (ISBN)

Discover the soul of Japanese cuisine right in your kitchen with Taste of Japan: Authentic Flavors for Home Cooks. Imagine each meal as more than just food; it's a connection to tradition, nature, and the joy of cooking with intention. This book guides you through the essentials-from delicate, umami-rich miso soups to the satisfying sizzle of a homemade tempura, and from soul-soothing ramen to the art of sushi-making.

Each recipe has been chosen and crafted to feel approachable yet true to its roots, allowing you to recreate these beloved flavors and rituals, even if you're new to Japanese cooking. Inside, you'll find the stories and techniques that turn simple ingredients into unforgettable meals, whether for a quiet dinner or a lively gathering.

With Taste of Japan, every dish you prepare will bring you closer to the spirit of Japanese food culture-thoughtful, balanced, and deeply satisfying. Let this book be your invitation to slow down, savor each bite, and bring a world of authentic flavors into your home.

Chapter 1

Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art

My grandmother’s kitchen was inside an old, small wooden house perched on top of a mountain in a rural Japanese village. Her footsteps tapped on the wooden floorboards, and the water heater hissed away on the stove every morning. There was something humble about the kitchen itself, with its modest tools and ingredients, but in her hands, it became a lovely space where simple components were transformed into richer creations that lingered long after the meal was over.

I called my grandmother obaachan. My obaachan worked with quiet precision. She prepared meals deliberately and slowly, honoring each ingredient as if it had a story all its own. Starting with the basics passed down through our family—she would begin. Cooking wasn’t a luxury for her; it was about balance, consideration for the people around the table, respect for the season, and reverence for the food itself.

Her kitchen had an old wooden rice chest as its centerpiece. Each morning, she would scoop short-grain rice from it with practiced ease. Rice was not just a side dish in our household—it was the heart of every meal. My grandmother would say, “Wherever there is rice, that is where everything begins.” She taught me how to rinse it carefully, swirling the milky water until it ran clear—a ceremony of cleansing and preparation. As the rice cooked, its earthy, gentle aroma would fill the room, signaling that the meal had begun.

In the evenings, she often made dashi, the basic stock from which we built all our dinners. Her dashi was lightly prepared, a buttery addition to any dish, with kombu and katsuobushi blended. She would simmer the kombu in water, letting it cook slowly to draw out the sweetness of the kelp. Then, she would gently add the katsuobushi—thin shavings of dried bonito—that swirled in the pot like leaves caught in a breeze. The smell was intoxicating, smoky yet humble, hinting at something extraordinary.

There was a time when she taught me to make miso soup, a dish that looks deceptively simple but is intricately layered. She poured dashi into a small pot and added chunks of tofu and handfuls of sliced green onions. Finally came the miso—a thick paste made from fermented soybeans. “That spoon,” she insisted with a smile, as she spooned it into a miso-koshi (a fine mesh strainer), carefully dissolving it into the soup with gentle circles. The broth became a comforting elixir that warmed you from the inside out, though a bit of miso clouded the liquid. “It’s like meeting a good friend,” she said, “who’s always there to comfort you, whatever the season.”

Rice, dashi, miso soup—these basic recipes were more than food; they were rituals that anchored us to something bigger than ourselves. I loved the basics, but my grandmother’s kitchen held other treasures, small family secrets passed down through generations. One such treasure was tamagoyaki, a rolled Japanese omelet. It looked easy enough to make, but it required a steady hand and a patient heart.

She would liquefy eggs with a little sugar, soy sauce, and a dash of dashi. Brushing the pan lightly with oil, she heated a square tamagoyaki pan. With practiced hands, she poured a thin layer of egg mixture into the pan until it spread evenly across the surface. As it set, she would roll it with her chopsticks, pulling it toward one side and adding another layer of egg. Layer by layer, she created a neat, golden roll. She would then carefully slice it into soft, layered sections—slightly sweet, slightly savory, with a subtle dashi flavor.

“They say tamagoyaki is a test of patience,” she told me. “If you rush it, it will fall apart.” Watching her, I learned that cooking is not merely technique—it is about mindfulness and respect for the process. She taught me that even something so simple could be made extraordinary if approached with care.

Pickling was another tradition in her kitchen—an art of preserving the essence of vegetables long after their season had passed. Anything in season—cucumbers, radishes, daikon, even fruits—would become pickles, or tsukemono. Each type of tsukemono had its own method: some were lightly salted and pressed, while others were packed in rice bran for added flavor. Small touches of red chili or shiso leaves would transform these pickles into bursts of flavor alongside rice and miso soup. She stored them with care, knowing they would brighten meals during the winter months, a reminder of the season’s bounty.

Once, I asked her how she never measured anything. She giggled and said, “When you cook long enough, you begin to listen to the food. It tells you what it needs.” Her senses were her tools; she didn’t need scales or measuring spoons. She would pinch a bit of salt between her fingers, adjust the seasoning by the scent of the pot, and somehow, it always turned out perfectly.

One of the simplest and most satisfying rituals in her kitchen was making furikake, a type of rice seasoning. The kitchen would smell warm and nutty as she toasted sesame seeds in a dry pan. She would crumble sheets of nori, add dried fish flakes, and sprinkle a little salt. I kept a small jar of this mix, and when sprinkled over rice, it transformed a plain bowl into something flavorful and comforting. The topping wasn’t grandiose, but it allowed the depth and richness of the rice to shine. Even a simple topping could make a big difference.

As the seasons changed, so did the cuisine in her kitchen. In summer, she made refreshing cold salads with the simplest dressings; soy sauce, rice vinegar, and sesame oil, with perhaps a sprig of green onion or a little grated daikon for garnish. Of everything she taught me, maybe the most important lesson was how to make a salad dressing. Though it sounds simple, the combination of acidity, saltiness, and a hint of sweetness was spot-on. This dressing offered a cool respite from the heat, making crisp vegetables tangy and vibrant.

Her kitchen had a different rhythm in winter. I remember her cooking oden—a warming stew of daikon, boiled eggs, and other ingredients in a light dashi broth. She would cook it slowly, letting the flavors build over hours, each ingredient soaking up the richness of the broth. Once the oden bubbled gently, we sat by the hearth and waited patiently until it was ready to eat. When we ladled it into bowls, each bite was a celebration of warmth, wrapping around us like a soft blanket against the cold.

Green tea was one of the greatest joys in my grandmother’s kitchen. Using high-quality tea leaves, she kept them fresh in a tin. She heated the water to exactly the right temperature—not too hot, so as not to scald the delicate leaves—and poured it over the tea, steeping it briefly before filling small, handleless cups. The taste was subtle, grassy, and slightly bitter, lingering nicely on the tongue. Drinking tea with her was a moment of stillness, a pause for reflection. It wasn’t just part of the meal—it was practically a ritual in itself.

My grandmother spent her days in her small kitchen, cooking with simple tools and well-worn pots, teaching me the true essence of Japanese cooking. It wasn’t about slavish devotion to recipes or the pursuit of perfection—it was about humbling yourself before each ingredient, respecting the cycles of the seasons, and sharing the experience with loved ones. Every meal she prepared told a story, expressed through the calm simmer of dashi, the gentle roll of tamagoyaki, and the careful selection of rice.

She taught me that Japanese cooking isn’t about complexity—it’s about simplicity. Even the humblest ingredients, when handled with care, revealed their true essence in her hands.

Recipes

Traditional Japanese Soup Stock (Dashi)

Japanese cuisine is built on dashi, the backbone of soups, sauces, and simmered dishes. Quick to make, umami-rich, and crafted from kombu (kelp) and katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes), it marries the oceanic depth of kombu with the smoky richness of bonito.

Ingredients

- A 10 cm piece of kombu

- 2 cups (500 ml) cold water

- 15 g (about 1 cup) katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes)

Instructions

- The white powder on the kombu’s surface enhances flavor, so gently wipe it with a damp cloth—do not rinse.

- Place the kombu in a pot with cold water and let it soak for 15–30 minutes to release its flavor. (This step is optional but adds depth.)

- Slowly bring the water to just below boiling. Remove the kombu as soon as small bubbles form.

- Turn the heat to a gentle simmer, add the katsuobushi, and simmer for 2 minutes. Then turn off the heat.

- Strain the dashi, allowing the golden stock to sit for a moment. If not used immediately, store it in the fridge for up to 3 days.

Shoyu (Soy Sauce-Based) Soup

Shoyu soup is a light broth made by combining soy sauce with dashi. It’s perfect as a base for noodle soups like udon or soba or as a standalone vegetable soup.

Ingredients

- 4 cups (1 liter) dashi

- 2–3 tbsp soy sauce (preferably *usukuchi* for lighter flavor)

- 1 tbsp mirin

- A pinch of salt (to taste)

Instructions

1. Heat the dashi in a pot over medium heat.

2. Add the soy sauce and mirin, stirring until well combined. Adjust seasoning with a pinch of salt to achieve a light, balanced flavor.

3. Serve as a base for other dishes, hot or as a side with noodles or tofu.

Perfectly Steamed Rice

Steamed rice is the heart of Japanese meals, prepared with care to achieve a soft, slightly sticky texture that pairs...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.6.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-095624-4 / 0000956244 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-095624-8 / 9780000956248 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich