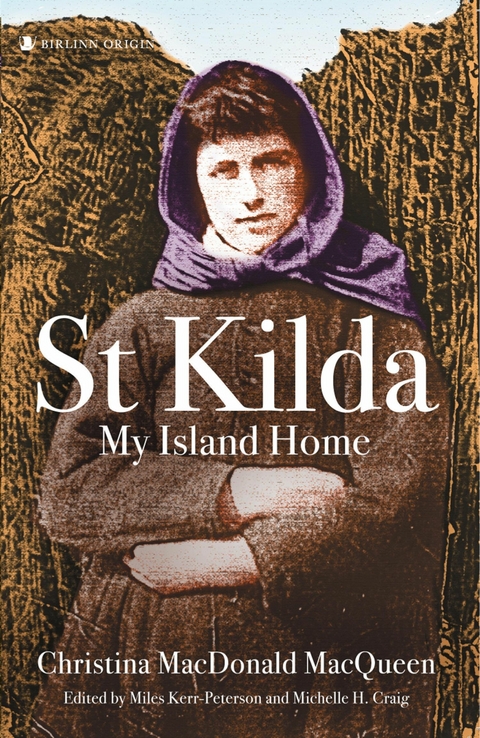

St Kilda: My Island Home (eBook)

176 Seiten

Birlinn Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78885-773-4 (ISBN)

Dr Michelle Craig is a Scottish historian at the University of Glasgow, specialising in book and archive history and information studies. Dr Miles Kerr-Peterson is an independent scholar, primarily interested in early modern Scottish politics, culture and society, but also regional studies related to Scottish Lordship throughout its history.

Christina MacDonald MacQueen (1884-1959) was born on St Kilda and grew up there at the close of the 19th century. Yearning for the bright modern world beyond the island, she was the first woman to leave of her own accord in 1909, settling in Glasgow. During the crisis that led to the islands' evacuations in 1929-30, she wrote a series of passionate articles about her childhood and the history of the islands. These writings about St Kilda offer a personal and uniquely female perspective on the island's story and its imminent abandonment. This book includes all seventeen of her articles, which tell the full history of the island as she understood it, and sets their publication against the dates of the evacuation. These are complemented by a historical introduction and commentary. Despite extensive literature on the story of St Kilda, Christina's contributions have been largely overlooked by historians, though they offer valuable insights into the island's history and the evacuation's impact. To compliment the articles written by Christina, this volume includes a collection of photographs taken by her husband, Robert Chalmers, in 1930.

Dr Michelle Craig is a Scottish historian at the University of Glasgow, specialising in book and archive history and information studies. Dr Miles Kerr-Peterson is an independent scholar, primarily interested in early modern Scottish politics, culture and society, but also regional studies related to Scottish Lordship throughout its history.

1884–1903:

Growing up on St Kilda

On 10 February 1884 Christina MacDonald MacQueen was born at 10 Main Street, Village Bay, on Hirta.1 Hirta is the main island of the St Kilda archipelago, and was the only one permanently inhabited. She was born into a small community: three years prior the population of the island was a mere 77 individuals, spread among 19 households.2 Christina’s articles paint the picture of her island home in brighter colours than we can, so we will restrain ourselves in this introduction to outlining her life and childhood up to 1930. We will then continue her story around her writings.

Christina’s parents were Marion MacDonald and Donald MacQueen. She was their sixth child, although only the third to survive infancy. From the 1911 census we learn the horrible fact that Marion had given birth to a total of twelve living children over her lifetime, with only four surviving to that time (eight died in infancy, two as adults). Infant death plagued St Kilda. There was around a 50 per cent child mortality rate through most of the nineteenth century due to tetanus, compared to industrial Britain’s average rate of around 15 per cent.3 Christina was a very lucky baby. George Murray, the schoolmaster on St Kilda from 1886 to 1887, describes in his diary the agonising illness of baby MacKinnon, a contemporary of Christina: born on 14 December 1886 ‘Child large and very promising. Mother doing well’, but taken ill on the 22nd and died on the 27th. ‘In the grave which was opened I saw the coffins of its two little brothers that died the same way.’4 Christina mentions infant mortality at the end of her article of 28 December 1929, and attributes the cure of the blight to the minister Angus Fiddes, who served on the island from 1889 to 1901, and who took it upon himself to seek midwifery training on the mainland.

Christina was most likely named after Marion’s mother, Christina MacKinnon, 1819–87, although Marion also had a sister of the same name who had died in 1880. The name itself was one of the rarer forenames of the island; the more common female names at the time were Catherine, Rachel, Anne and Mary.5 Marion’s father was John MacDonald (1811–89). Christina’s paternal grandfather Donald (see below) had died in 1880, while all her other grandparents would be dead by the time she was six years old. However, she would be blessed by having two aunts on her mother’s side, Margaret MacDonald (1839–1926) and Catherine MacDonald (1842–1912).

In the 1891 census, we find her in her childhood home as part of a household of six: Donald and Marion with 14-year-old Ann, 11-year-old Norman, 7-year-old Christina and 5-year-old Donald. Their little home had only three rooms with windows: two bedrooms and a kitchen. In her article of 14 December 1929, Christina mentions stories by the fireside, and the presence of spinning wheels and a loom hanging from a roof beam. The spinning wheels were used by the women to make thread which Donald wove on the loom. Number 10 Main Street had been built around 1861–68, so was relatively new when Christina was born. It stood immediately adjoining the west side to the little path that led to the circular burial ground, and was almost in the centre of the settlement in Village Bay (see map). In total there were sixteen of these modern houses on Hirta and numerous older dwellings-come-storehouses or byres called ‘blackhouses’. At the time of that census three of these blackhouses were still being used as dwellings, such as that of old Rachel MacCrimmon, who Christina describes in her article for the Scots Magazine. The whole island spoke Gaelic and her articles show that English was also limited among many of the older generation, such as Rachel.

Christina’s father, Donald, was the third in succession to bear that name (while her brother was the fourth and last to be born on Hirta). The first had been born on St Kilda in the mid-eighteenth century. In 1720 and 1727 two epidemics devastated the population of St Kilda, and Christina describes these in detail in her article of 14 December 1929 (although she mistook the year for 1729). Before this great mortality, Hirta’s population had been between 180 and 200. After, it was around 42: nine men, ten women, fifteen boys and eight girls. Eleven of the males – three men and eight boys – had been stranded on Stac an Armin over the winter of 1727–28 and escaped the ravages of smallpox. Around twenty-one households had been reduced to four.6 The feudal superiors of the islands, the MacLeods of Dunvegan, thereafter sent a handful of settlers each year to repopulate the islands. It has been alleged these settlers were felons, sent by the MacLeods as punishment, although this has not been confirmed by contemporary evidence. Christina certainly bristles against the assertion in her letter to the Oban Times of July 1930. Among the new settlers was one Finlay MacQueen, although there had been MacQueens on Hirta prior to 1727, and there was even a legend that the first settler on the island was an Irishman called ‘Macquin’.7 Finlay was born sometime around 1695 on Uist. He married a woman with a MacDonald surname, presumably one of the survivors from the pre-epidemic St Kilda families.

Among Finlay’s children was a John MacQueen (1750–1830), who married an Ann MacDonald in 1769. One of John’s children was Donald MacQueen (1781–1839), who married a Mary MacCrimmon in 1802. Among Donald and Mary’s children was the second Donald MacQueen (1804–80), who married a Kirstie Gillies in 1833. An 1860 plan of Village Bay shows a long strip of land in the occupation of Donald MacQueen II, which was to the front of where number 10 would later be built. A ‘blackhouse’ at its top on Main Street (which survives next to number 10) was his dwelling, built in 1834.8

Among Donald II’s children was the third Donald MacQueen, born in 1840, Christina’s father. In 1862 this Donald had a son with Ann MacDonald. He was the well-known and photographed Finlay MacQueen (1862–1941), master bird catcher and climber. Donald III married Mary Gillies in 1868. She died in 1871. On 2 September 1873, he married Marion MacDonald, Christina’s mother.9 In 1883, the year prior to Christina’s birth, Donald was selected, alongside Reverend John MacKay and Angus Gillies, to represent the islanders when the Napier Commission arrived on Hirta to discuss crofting reform. A major grievance was the lack of shipping communication between St Kilda and the rest of Scotland over the winter, something Christina consistently complains about in her articles. Donald was interviewed and spoke confidently on rents, fowling, export prices and the need for a pier to help with fishing.10

Christina seems to have had a typical childhood on the island. This is outlined in detail in her articles, although she only briefly mentions her schooling as an aside in her final article. From 1879 a schoolteacher was employed on the island, although few teachers stayed much longer than a year, and their quality varied: one in the late 1890s knew no Gaelic and was hence of little use. From 1890 to 1900 the minister, Angus Fiddes, seems to have borne the responsibility. Schooling took place between the ages of 6 and 14. The schoolhouse was built in 1898, when Christina would have been about 14. Prior to this schooling was probably carried out in the church. The children were taught arithmetic, reading in both Gaelic and English, the history of Scotland, and geography. They were also taught to memorise scripture at Sunday School. From the 1880s the teaching on Hirta had included more English language. Christina would have been one of those described by the visitor Heathcote in 1900 as ‘the rising generation who speak it [English] quite well’. This enhanced English education allowed many of the island youth to leave the island for places like Glasgow.11

In the 1901 census, taken when Christina was 17 years old, there were eight people living in number 10: Donald III and Marion, and their children, Christina and Donald IV, as well as 9-year-old John and 6-year-old Mary. The couple’s eldest son, Norman, who had also been present in 1891, was a 21-year-old, and was also still living at home alongside his 24-year-old wife, also named Christina.

__________

1 National Records of Scotland Statutory Register of Births III/4 7. That month the minister of St Kilda, John MacKay, refused to baptise baby Christina, as her father refused to submit to church discipline over some unrecorded infraction. Andrew Fleming, The Gravity of Feathers: Fame Fortune and the Story of St Kilda (Birlinn, 2024), 140.

2 Seventeen of the households were islanders, then there was the Manse with the minister’s household, and the Factor’s House, which was occupied by Ann MacKinlay, the nurse and teacher.

3 Roger Hutchinson, St Kilda: A People’s History (Birlinn, 2014), 134.

4 ‘McKinnon’ is used here as Murray’s spelling, although MacKinnon was the more usual spelling. Murray also records another baby dying of the illness, then in heart-wrenching detail of a girl aged ten. Maureen Kerr, George Muray: A Schoolteacher for St Kilda, 1886–87 (Islands Books Trust, 2013), 78–82, 90–1, 100.

5 George Seton, St Kilda (Birlinn, 2019),...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.5.2025 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | female history • female perspective • firsthand accounts • history of St Kilda • Island at the Edge of the World • Island History • Local History • Local Scottish History • Scottish History • Scottish Island History • St Kilda History • true accounts • women's studies |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-773-9 / 1788857739 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-773-4 / 9781788857734 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich