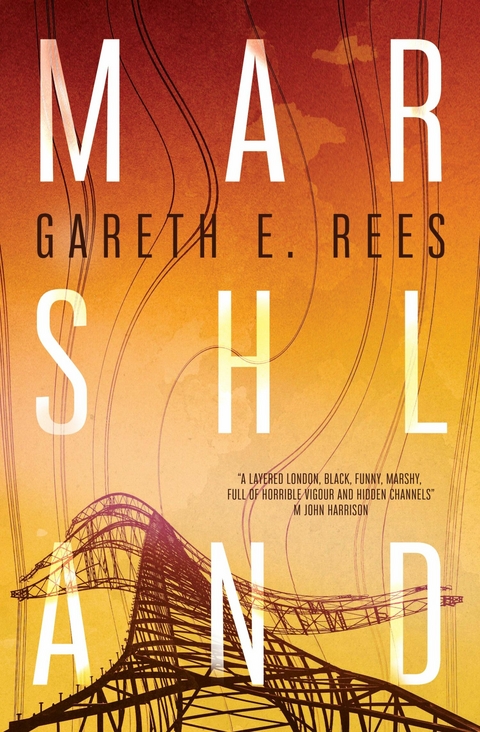

Marshland (eBook)

312 Seiten

Influx Press (Verlag)

978-1-914391-29-3 (ISBN)

Gareth E. Rees is an author of fiction and non-fiction. His books include Sunken Lands and Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson), Car Park Life and The Stone Tide (Influx Press). He has contributed to numerous weird fiction and horror anthologies and his stories have been selected for Best British Short Stories 2023 (Salt Publishing) and The Best of British Fantasy 2019 (Newcon Press). His first short story collection, Terminal Zones, was published by Influx Press in 2022. Rees is also a songwriter, guitarist and vocalist in The Dirty Contacts and Black Arches, and has collaborated on musical projects with Polypores, The Revenant Sea and Jetsam. He lives in Hastings.

My first daughter, Isis, was born in Homerton Hospital in November 2008. My parents looked after our cocker spaniel, Hendrix, while we adjusted to our new life. Our ground-floor flat became a cocoon. We warmed bottles and washed muslin cloths. We worked through boxes of congratulatory chocolates. We welcomed visitors and stacked teddy bears in the corner.

We did the parent thing.

When Hendrix returned, I realised, with queasy vertigo, that we were a proper family. The sort you see in children’s drawings standing next to a house beneath a smiling sun. So it was on a bright, freezing December afternoon that my wife, Emily, and I took Isis out for the first time. We went to Millfields Park on the borderland of the marshland. Daddy, Mummy, baby, dog.

The enormous pram seemed ridiculous as we wheeled it into Millfields. Isis was ensconced in layers of white. All you could see was a pixie nose and her eyes, freshly woken from myopia, taking in the elms passing overhead. I took some photos, feeling like a tourist who had just quantum-leaped into someone else’s life.

As we walked down through the park towards the River Lea and the marshes of East London which lay beyond, the city’s gravity began to lose its hold and my happy narrative fell to pieces. From the water’s edge a shape moved towards us at speed. Though small in the distance, I could tell it was a bullmastiff or some similar barrel-chested Hackney man-dog. I knew right away it was heading for us. It didn’t waver from its route, thundering on the frozen ground, growing closer and larger.

Emily and I stopped walking and watched it hurtle up the slope. Hendrix sniffed the grass, oblivious. I removed his lead from my pocket and called him, but it was too late. The dog was upon us. It ground to a halt before Hendrix and the two began to spin. The mastiff’s tail, stiff and vertical, quivered with aggression. Hendrix’s tail was slung low as he snarled back. A voice echoed across the park as a dreadlocked man staggered towards us with a lead.

I reached out to grab Hendrix’s collar. It was like pushing the ‘ON’ button on a blender. The two dogs whirled into a blurry frenzy round my arm, barking, teeth bared. I staggered back in pain, bitten. Emily cried out, jerking the pram away. The animals were separated but circling again.

‘Sorry man,’ wheezed the owner in a Caribbean accent, shaking his head. ‘He’s a puppy. You okay?’

He had a hold of his dog, but it was too late. The idyll was shattered. My family dream exposed for what it was: an artificial construct, fragile as glass. Isis screaming her tiny lungs out. Emily shaking her head in disappointment, me staggering around saying, ‘shitshitshit’. A scenario which would characterise many subsequent family occasions.

A few months later, I saw them again in Millfields, this time on the Lee towpath. I spotted the dog first. He ran up to Hendrix, chest puffed out, whorls of hot air snorting from his nostrils. Then I recognised the owner. The dreadlocks, the deep vertical lines on his face. He wore a dark blue tracksuit and smoked what was either a rollup cigarette or the last remnant of a joint.

The dogs circled. Mr Mastiff’s dog rose up on his hind legs and gave Hendrix a couple of right hooks. Hendrix took two steps backwards and plunged into the river. All that remained on the water’s surface was a cloud of dirt. His head bobbed up and he started paddling against the current. He moved absolutely nowhere at first, then backwards as he lost strength.

‘Sorry, sorry, sorry,’ Mr Mastiff mumbled.

I dropped to my belly and tried to reach into the water. The ledge was too high to get my hands on him.

‘My legs,’ I said to Mr Mastiff. ‘You’ll need to hold my legs.’

I piled my mobile phone, keys and loose change on the concrete, lay on my stomach and said, ‘Okay – now.’ Mr Mastiff held my ankles and slid me forwards until I was dangling over the water, clawing at Hendrix’s collar.

If I’d been someone else passing by – if, say, I’d been myself on one of my walks – I would have returned home and written excitedly about seeing a Caribbean man in a tracksuit doing ‘the wheelbarrow’ with a scruffy white bloke on the edge of the river while a tiny dog swam backwards. But I wasn’t the observer. I’d become one of those people you see doing inexplicable things when you come to the marshes. I’d been exploring the place only a matter of months and already I had been assimilated into the weirdness. For this reason, I consider that moment – being dragged back over the ledge with Hendrix, soaking wet – as a kind of baptism.

From that day forth, I named this place ‘Entropy Junction’. It was the frontier crossing on the borderland between city and marshland, where the competing gravities of two worlds created a zone of chaos and disorder.

Things happened here.

It was Hendrix, a cataract-stricken puppy, jet black and bumbling, who first brought me to this frontier, shortly after my wife Emily and I moved from Dalston in the west of Hackney, to Clapton in the north-east of the borough. When he was strong enough to walk the distance, Hendrix led me away from Hackney’s Victorian terraces through Millfields Park. I remember the day well, the perfume of freshly cut grass and Hendrix’s tiny legs tripping over twigs. We passed a Jack Russell shitting pellets into a shrub. A jogger whooped, ‘Yeah!’ and boxed the air. Toddlers shrieked on the swings. A drunk lay on a bench, beer can on his belly oozing dregs. A suited man mumbled into a mobile phone. Two kids kicked a football. A murder of crows amassed by a bin. Then, at the bottom of the park, it all came to a halt.

At the River Lea, the park ended abruptly at a tumbledown verge, twisted with weeds and dandelions, iron bollards tilted like old tombstones, chain links snapped. Where you’d expect a towpath to be was, well, nothing. A soup of stone and soil poured into the water. Across the river a concrete peninsula bristled with weeds, empty but for an office chair, traffic cone and a Portaloo circled by gulls. A moorhen stared back at me from a rusted container barge. Beyond the corrugated fencing, geese flapped across a wide sky where pylons, not tower blocks, ruled the horizon. Near a footbridge, narrowboats were moored beneath a brow of wild scrub. Ruddy-cheeked people in Barbour jackets and mud-spattered wellies strolled across the river, followed by giant dogs, as if a time-space portal had opened between London and some faraway countryside.

This was my first encounter with the marshland. It was a place unmarked on my personal map of the city. Until now I’d perceived London as a dense, functional infrastructure spreading out to the M25. Each citizen’s experience depended on the transport connectivity between their workplace, home, and favoured zones of entertainment. Londoners journeyed through their own holloways, routes worn deep into their psyche. The idea of deviating from this psychological map hadn’t occurred to me. I assumed I lived in a totalitarian city. London’s green spaces were prescribed by municipal entities, landscaped by committees, furnished with bollards and swings. There was no wilderness. There was no escape. You couldn’t simply decide to wander off-plan. Or so I thought.

Now my dog had brought me to a threshold between the city I knew and a strange semi-rural wetland known as ‘the marshes’. On one side of the river, London was in hyper flux, perpetually regenerating, plots as small as toilets snapped up by developers, gardens sold off, Victorian schools turned into apartments, bomb sites into playgrounds, docklands into micro-cities, power stations into art galleries. Everything was up for grabs. On the other side of the river – a stone’s throw away – lay a landscape of ancient grazing meadows scarred with Second World War trenches, deep with Blitz rubble, ringed by waterlogged ditches, grazed by long-horned cows, where herons and kestrels hunted among railways, aqueducts and abandoned Victorian filter beds. It was untamed, unchanged in some parts since the Ice Age. It had not yet been claimed by developers. It was nobody’s manor.

Discovering this place was like opening my back door to find a volcanic crater in the garden, blasting my face with lava heat, tipping reality topsy-turvy.

In that year when Hendrix dropped off the edge of London into the Lea, the riverside was the booming frontier of Hackney’s redevelopment. For decades the Lea had been dominated by Latham’s timber yard and other warehouses. Now these edifices were being torn down and the skeletons of waterfront flats rose in their place, wrapped in wooden hoardings. Among the graffiti tags, guerrilla advertising stickers and splashes of dog piss, developers’ posters envisioned the future in neat lines and diagrams. There was a phone number you could ring to discuss the price of a space in the sky that hadn’t been built yet. Above the rim of the hoardings, yellow...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Schlagworte | deep topography • Gareth E. Rees • Gareth Rees • Hackney • Hackney Marsh • Hackney Marshes • Influx • Influx Press • London • London writing • Marshland • M John Harrison • Nature writing • Olympics • psychogeography • Rees • Sunken lands • Terminal Zones • The Stone Tide • Unofficial Britain |

| ISBN-10 | 1-914391-29-2 / 1914391292 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-914391-29-3 / 9781914391293 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich