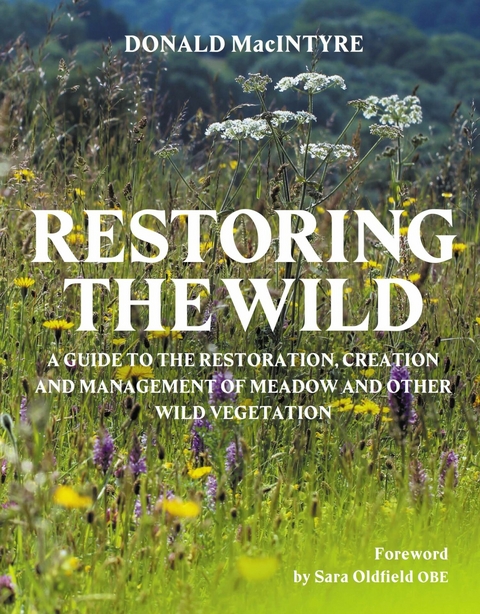

Restoring the Wild (eBook)

272 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4439-3 (ISBN)

Inspired by his mother from an early age, DONALD MacINTYRE has 44-plus years of experience in practical vegetation creation and restoration, in the wild. A former academic and researcher, Donald owns Emorsgate Seeds, the UK's largest producer of native seed.

BIODIVERSITY, SPECIES, ECOTYPES AND ECOSYSTEMS

This chapter looks at the astonishing diversity of life in meadows and other wild herbaceous vegetation and discusses how individual wild plants cluster into distinctive local ecotypes, how ecotypes cluster into distinctive species, how species cluster into communities, and how communities build ecosystems.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is the sum of the genetic variation of all the living organisms in a unit of volume. Take, for example, a cubic metre of meadow. With meadows, as with most habitats, there is far more living biomass and more genetic diversity below ground than there is above ground. The genetic diversity between and within all life forms, above and below ground, is the basic and fundamental measure of biodiversity. By this measure, a cubic metre of meadow is more biodiverse than the contents of an equivalent volume of the deep freeze of a gene bank.

We can measure and record the genetic code, but we cannot see and read it with our naked eyes. We can, however, see the diversity of species in a meadow, and the variation within those species. The Convention on Biological Diversity, Rio de Janeiro (1993), defines biodiversity as follows:

Every living thing, including the natural patterns they form. Including every species and all the genetic differences within each species. The variety of ecosystems: forests, drylands, wetlands, mountains, lakes, rivers, agricultural lands, seas and islands where living creatures, including humans, animals, insects and plants, that form a community, interacting with one another, and with the air, water and soil around them.

High genetic variation (biodiversity) across species, between ecotypes within species, between individuals within ecotypes, and within individuals, is important in grassland restoration and creation because it creates genetically robust communities that are best able to survive and respond to environmental heterogeneity across space and time.

Common Broomrape (Orobanche minor) and Bee Orchid (Ophrys apifera), delightful examples of the diversity of our native flora that may occasionally be found in surviving wild places.

Species, Ecotypes and Communities

Species

A species is a natural grouping of individuals that cluster and share with each other a common set of defining features that are not shared with other species. These salient defining features may be the visible morphology (the macroscopic and microscopic phenotype) of the species, or unique information held in DNA base sequences (the genotype), or a combination of both. Each defining feature of a species will have a genetic mean and a genetic variance. The mean is the average measure of that feature for the species, and the genetic variance is the spread of the genetic measure of that feature around the mean. The genetic variance of the defining features of two closely related species must not overlap, otherwise they are the same species. For a more critical account of species concepts see Barraclough and Humphreys (2014).

The following page presents a schematic representation of the genetic mean and variance of two related species that differ in height. Plotting frequency against feature size will often produce a symmetrical or skewed normal curve.

The individuals of a species usually share a common gene pool, and experience few barriers to interbreeding with each other, except that individuals of outbreeding species are not normally able to self-fertilize, and individuals of selfing species are not normally able to cross with other individuals of the same species.

We are indebted to science for our understanding of the origin of species, and in particular to Charles Darwin (1859) for ‘evolution by natural selection’, to Gregor Mendel (1866) for ‘the mechanism of inheritance’, and to Watson and Crick (1953) for ‘the structure of DNA’.

Hedge Bedstraw (Galium album), Bird’s-foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) and Yellow Rattle (Rhinanthus minor) growing together in the wild.

Figure 1: Schematic normal distribution showing genetic mean and genetic variance for height of hypothetical short and tall species. Note that the genetic variance for height of the two species does not overlap.

Flower spikes of Common Spotted Orchid (Dactylorhiza fuchsii) in clonal pairs from a single population exhibiting considerable genetic variation between pairs.

Not all species in the plant world are equal. At one extreme are those species that are largely asexual, reproducing by vegetative means or by apomixis. These asexual species tend to be uniform, any existing heterozygosity is locked in, and any evolution is slow and step wise, mediated by somatic mutation (or other mechanisms as yet unknown). This mode of reproduction can produce arrays of distinct clones. Many of these have been named, and are referred to as ‘micro-species’. The origin of micro-species is uncertain. They may be simple ‘sports’, or they may be more complex accumulations of somatic mutations in response to natural selection by a process akin to speciation, over very long periods of time. There are around 260 micro-species of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), 100 or so micro-species of Wild Rose (Rosa canina), and 200 or so micro-species of Hawkweeds (Hieracium sp).

At the opposite extreme are those species that reproduce sexually, are highly fertile, and have weak barriers to hybridization between related species. The result is that such species are very variable, may exist as complex hybrid swarms, and are often actively evolving. As may be expected, it can be difficult to define the limits of these species with any precision. A good example of a dynamic evolving genus is Dactylorhiza (the Spotted Orchids). Species of Dactylorhiza readily hybridise frequently with each other, and genetic variation within species is huge. Interestingly, this genetic variation is nicely demonstrated in the wild in hybrid swarms involving Common Spotted Orchid and Southern Marsh Orchid. Dactylorhiza is polycarpic and may produce clonal flower spikes side by side following division of the tubers. These clonal pairs enable comparison with other paired individuals nearby, thus demonstrating the environmental influences on the phenotype, and revealing by observation the astonishing diversity of genetic variation in Dactylorhiza. The images on the previous page provide a few examples taken from a single population.

Ecotypes

For simplicity, we group together, as ecotypes, all those below-species ranks sometimes used in classification (such as sub-species, variety, sub-variety, form), while retaining cultivar for the cultivated forms that are derived from the artificial breeding of wild species.

An ecotype is a distinct population within a naturally variable wild species, and ecotypes are a natural selection response to climatic, edaphic (nature of the substrate) and biotic (interactions with other species) factors, or to isolation. Different ecotypes within a species may be distinguished one from another by defining morphological or genetic features, and often a defining place of origin.

Species and ecotypes are different. Like species, individual ecotypes may be confined to one location, or may be found at different locations. However, the defining features of a species will have a genetic variance that does not overlap with that of related species (otherwise they would be the same species). The salient defining features of an ecotype have means that are distinct from those of other ecotypes of the same species, but the variance of the defining features usually overlaps with that of other ecotypes of the same species (otherwise the ecotype would be a species).

Figure 2: Schematic normal distribution showing genetic mean and genetic variance for height of hypothetical short and tall ecotypes. Note that the genetic variance for height of the two ecotypes overlaps.

Figure 2 is a schematic representation of ecotypes with frequency plotted against feature size, in this case inflorescence height. The frequency distribution of short and tall ecotypes takes the form of two overlapping normal curves with different means.

Wild ecotypes are frequent throughout the wild British and Irish flora. They are a huge reservoir of living biodiversity, essential for the proper functioning of ecosystems. They convey a local sense of place, they have heritage value, their scientific and utilitarian value is priceless, and they are a living genetic response to a changing environment, in both space and time. Therefore ecotypes are an important ecosystem component of restored, created and established species-rich meadows and other herbaceous vegetation, as is the dynamic evolutionary process that generates and sustains ecotypes.

Communities

Communities are assemblages of individuals of different species. The plant-to-plant and species-to-species interactions within a community are critical for determining the structure and the dynamics of the community (Bilas et al., 2020). Those interactions may be by wired communications between plants mediated by mycorrhizal hyphae, parasite/symbiont/host interactions, or wireless communication mediated by volatile emissions and root exudates (Sharifi and Ryu, 2020), as well as direct and indirect physical, chemical and radiological contact between plants (Smith et al., 2020, and Veits et al., 2018). Community...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Garten |

| Schlagworte | conservation • Ecology • habitat creation • land management • land planning • meadow creation • meadow renovation • seed sourcing • Wildflowers |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4439-8 / 0719844398 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4439-3 / 9780719844393 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich