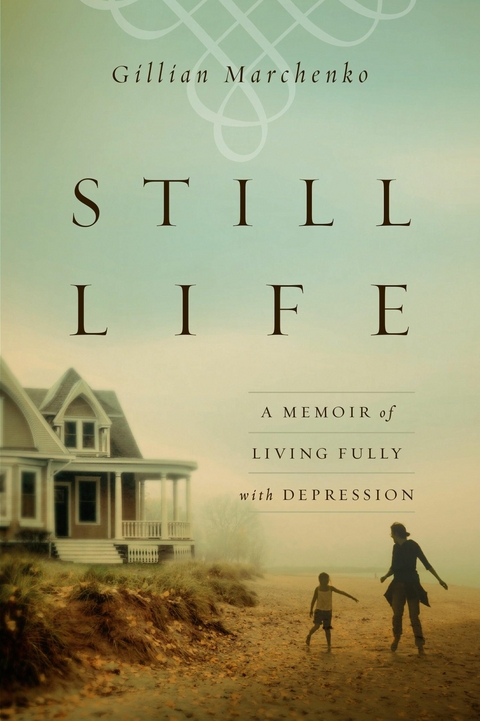

Still Life (eBook)

192 Seiten

IVP (Verlag)

978-0-8308-9924-1 (ISBN)

Gillian Marchenko is an author, speaker, wife, mother and advocate for individuals with special needs. Gillian's first book was Sun Shines Down, and she has written for publications such as Chicago Parent, Thriving Family and Today's Christian Woman. She and her husband, Sergei, spent four years as church planters with the Evangelical Free Church of America in Kiev, Ukraine, and they now live with their four daughters in St. Louis, Missouri.

Gillian Marchenko is an author, speaker, wife, mother of four daughters and advocate for individuals with special needs. Her memoir, Sun Shine Down (T. S. Poetry Press), chronicles her experience having a baby with Down syndrome while serving as a missionary in Ukraine.Gillian writes and speaks about parenting kids with Down syndrome, faith, depression, imperfection and adoption. Educated at Moody Bible Institute, she previously served with the Joni Friends Chicago Teaching Team, helping churches cultivate inclusive environments for individuals with disabilities and their families. In addition to being featured in numerous radio interviews and guest blogging on several websites, Gillian has written for publications such as Chicago Parent, Thriving Family, Gifted for Leadership, Today's Christian Woman, Literary Mama, MomSense Magazine and EFCA Today. She and her husband Sergei spent four years as church planters with the Evangelical Free Church of America in Kiev, Ukraine, and they now live with their four daughters in St. Louis, Missouri.

two

Why Are You Smiling?

Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.

Oscar Wilde

A man with a deep voice answers the call and walks me through a preliminary questionnaire. Do you struggle with depressive thoughts? Yes. Is your mood often low? Yes. Do you have problems with sleep, concentration or sexual arousal? Yes, yes, yes. I snap my cell phone shut in tears after I answer the questions. It is spring time 2011, early afternoon on a weekday, probably around one o’clock.

A few days later, a representative from the clinical trial calls back while I work on a magazine article in the dining room downstairs. I clear my throat and concentrate on a steady voice. “I am interested in participating. The ad stated there is compensation?” Yes, there is compensation. I listen, but words don’t compute. I’m obsessed with the money all of a sudden. I’m an addict looking for her next fix. Why? Is it because a psychiatric trial for money instead of need is easier to stomach? I cut the man off midsentence. “I want to clarify—there is compensation, right?” Yes, compensation. His voice gets louder. He is agitated. My body weakens and starts to swoon, reminiscent of the first time a cop pulled me over for speeding in high school.

“I called a clinical trial for depression today after seeing an advertisement online,” I mention to Sergei later as he browns hamburger in a skillet in the kitchen for dinner. “They want people to test a new antidepressant.” Our kids (Elaina, eleven; Zoya, ten; Polly, six; and Evangeline, six) are scattered around the house. I have no idea what they are doing. It doesn’t occur to me to find out. I have become an absent mom, a guest in my home. A nice family friend who may notice the children once in a while and smile, but keeps to herself. Off limits. Shut down.

Sergei, as expected, objects to the clinical trial. “Why would you want to ingest unknown and undertested medicine? Aren’t you afraid of the side effects? What if they figure out the drug is dangerous?”

Born and raised in Kyiv, Ukraine, Sergei lived through the Chernobyl power plant disaster in grade school. It occurred sixty miles north of Kyiv, but wind and weather brought the tragedy to the front door of his fourth-story apartment building. The Dnipro River, which runs through the city, splitting it into two large land masses, the right and left bank, turned green. Radiation rained down on the country.

“I remember my mom called me in from outside. She told me to pack, that my brother and I would take a train to Russia to stay with my grandparents. They didn’t tell us what had happened. It was a scary time,” Sergei said. Rumors circulated. It’s been said that people who decided not to leave their homes near Chernobyl took sick and died. Others grew extra limbs, and lips swelled up to five times their original size. Residual damage of the explosion, although less powerful, still exists today, some say.

We met when I took a year off from college to teach English in schools and universities in Kyiv. On the airplane to Ukraine, our leaders told us no matter what, we were not allowed to date “the nationals.” I got off the plane at one o’clock in the morning, and one of the first people I saw was a young boy with long greasy hair, acne all over his face and a skeletal build. I joke that it was love at first sight, but it took us six months in Ukraine to fall in love. Sergei interpreted for the group I worked with, and at the end of the year he followed me to the States. We’ve now been married for thirteen years. Side effects and danger exist in Sergei’s world. It isn’t something you watch on television or read about in a book as I did in my tidy little upbringing in the Midwest.

My parents have owned and operated a weekly newspaper for over thirty years. I have a brother, Justin. One sister, Amy. I’m the baby of the family. My folks built and maintained a typical middle-class American life in a small town in Michigan. My childhood trauma included breaking my left arm two times, once near my shoulder and once in my wrist. Each time I rather liked the attention.

I field Sergei’s concerns for two or three minutes and start to cry: “I want to do this, Sergei. I want to be evaluated by a psychiatrist. And I can because it doesn’t cost anything.” My tears force my husband’s concession, and I decide not to mention the compensation. I’ve gotten my yes. Right now that’s all I need. Besides, he lives my struggles. He realizes I need help. We need help. And he knows me. He knows I would cry until he said yes.

Two weeks later I drive out to the suburbs of Chicago for the trial. They administer a quick medical exam: blood pressure, urine sample, reflexes, nose, ears, deep breaths while a cold stethoscope presses against my chest. I’m ushered into a tiny room with a small desk and two chairs and a sink in the corner, to complete yet another questionnaire.

A cheerful man with a salt-and-pepper beard goes down the list of questions. Trouble with sleep? Change in diet? Thoughts of worthlessness? Unable to get excited? Do you ever want to hurt yourself? Cloudy thinking? I answer the questions, smiling, jittery and nodding throughout, mostly yeses.

I’m showered and in clean clothes. I haven’t looked this good in a while, I decide: combed hair lacquered with Big Sexy Hair Spray, mascara, shimmery lipstick. But I’m concerned. This is one of the few times I’ve talked about my depression in the midst of an episode in the presence of someone other than my husband. Even while saying yes to all the questions, I attempt to act as if it is a social interaction with a long-time friend. Why this need to perform? On the inside, I deem myself a failure. I can’t do anything right. But on the outside? I want people to see me and think I have what they call “it” together.

“Mrs. Marchenko, our tests indicate you suffer from major depressive disorder. The numbers are low, some of the lowest I’ve seen. If the information is correct, then you are extremely depressed.” I nod my head and offer another shaky smile, attempting to project understanding and confidence.

But inside, I start to break down and break apart. Major depressive disorder. Sounds ominous and final. Sounds like a real honest-to-God mental illness. Is this what I wanted—confirmation of a cracked-up head? A loss of life? A saying of Jesus comes to mind: “For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it” (Matthew 16:25). Yeah, okay, but what about those of us who watch our lives drift away and we do nothing about it? What if we no longer know who we lose our lives for? What if there seems to be no purpose or way to stop it?

I reach my left hand up to my cheek and rub it for a second. I’m here, right? I’m still here. My toe starts to tap. The cheerful man’s lips transition from a smile to a straight line. He stares at me, his eyes attempt to pierce mine, but I don’t let them. I hold his stare but block the piercing. What does that say about me? That now, in this pivotal moment in my life, I still fake, or at least try to fake, my feelings?

It’s because I’ve disappeared already. At some point my body became a solid sheet of ice over a raging sea of emotions. The cold I put out has caused people to look past me. They started to see through me. Or not see me at all. And now I am a master at pretending—that is, in front of anyone but Sergei—because I hate the fear, the guilt, the paranoia. Freezing meant a final attempt to hold on to myself and not disappear: stay cold and get through the day.

But now I hear the diagnosis. I sit in an uncomfortable chair in a bare cream-colored room. In one moment my fingertips tingle. My feet begin to burn. I start to thaw.

No, I can’t thaw. No! I imagine myself starting to crack and break apart inside. When my siblings and I were kids, my mom took us ice skating. I don’t remember gliding across ice, but I remember my feet killing me afterward. Back at home, my mom ordered me to undress. “Take off your socks too. It’s best if you don’t have anything on your feet right now.” She set a bowl of tepid water in front of a chair. “Here. Sit. Put your toes in there.” I stuck my feet in the water, and pain shot up my legs. My feet were on fire, burning, burning, burning in a bowl of warm water. “It hurts, Mom. Make it stop,” I cried.

Now, at the clinical trial, I watch myself thaw. Hold yourself together, Gillian. Stay cold. Don’t break.

I suppose that as with frozen toes after ice skating, one must be stripped bare to start to thaw. I thought I wanted this—a diagnosis, more information, help—but now I don’t know. I don’t want to bring feeling back to my limbs, because I have no idea how to handle them. I want to scream: It hurts. Make it stop. Instead I stare past the cheerful man and smile.

“Why are you smiling? I told you that you test in the severe range of depression.” He waits for an answer.

“Um.” I clear my throat. “I don’t know why I’m smiling.” Sweat pours down my back between my shoulder blades. The cheerful man, who I assume is the psychiatrist but later find out conducts preliminary testing, looks at me with compassion. Cracks run up and down my body. Can he see them? I’m dripping. Is he...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.4.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Krankheiten / Heilverfahren | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Pastoraltheologie | |

| Schlagworte | Adoption • Bad Mom • Christianity and depression • Christian mom • christian mother • Christian with depression • Christian woman depressed • Christian women • church and depression • depressed • Depression • depression medication • depression therapy • God • Guilt • guilty • Healing • Hope • Major Depressive Disorder • Memoir • MoM • mother • Motherhood • motherhood and depression • overcoming guilt • parenting and depression • Shame • Special Needs • Women |

| ISBN-10 | 0-8308-9924-3 / 0830899243 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-8308-9924-1 / 9780830899241 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich