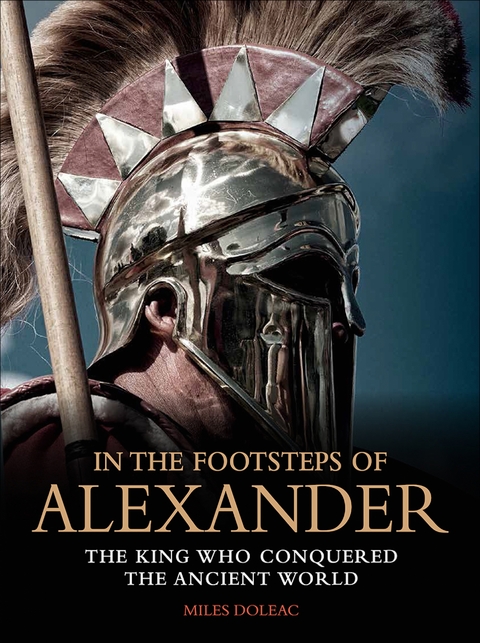

In the Footsteps of Alexander (eBook)

224 Seiten

Amber Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78274-186-2 (ISBN)

Divided into eight chapters, In the Footsteps of Alexander traces the physical and historical journey of the man who conquered Asia and was declared a god-king. Chapter one examines the Macedonian background and Alexander's rise to power; chapters two and three explore the invasion of Asia Minor and his first encounters with Persian armies at the battles of Granicus (334) and Issus (333); chapter four looks at the siege of Tyre (332) and the great victory over Persian king Darius at Gaugamela (331); chapters five and six follow Alexander's conquest of the outer reaches of the Persian Empire, from the battle of the Persian Gates (330) to the invasion of India and the battle of Hydaspes (326); while chapter seven examines the new cities he founded across Asia, including Alexandria, Antioch, and Kandahar; finally, chapter eight considers his death and legacy.

Including more than 200 photographs, illustrations, paintings, and maps, In the Footsteps of Alexander is a colourful, accessible examination of one of history's greatest military leaders.

In just 11 years, Alexander the Great's armies marched 22,000 miles (35,000 km), subjugated Asia Minor, the Levant, and Egypt, conquered the mighty Persian Empire, and invaded India. By the age of thirty, he had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world. And even after he died in 323 BCE, aged 32 and undefeated in battle, his legacy remained in the form of a Hellenized Asia and the Seleucid Empire. Divided into eight chapters, In the Footsteps of Alexander traces the physical and historical journey of the man who conquered Asia and was declared a god-king. Chapter one examines the Macedonian background and Alexander's rise to power; chapters two and three explore the invasion of Asia Minor and his first encounters with Persian armies at the battles of Granicus (334) and Issus (333); chapter four looks at the siege of Tyre (332) and the great victory over Persian king Darius at Gaugamela (331); chapters five and six follow Alexander's conquest of the outer reaches of the Persian Empire, from the battle of the Persian Gates (330) to the invasion of India and the battle of Hydaspes (326); while chapter seven examines the new cities he founded across Asia, including Alexandria, Antioch, and Kandahar; finally, chapter eight considers his death and legacy. Including more than 200 photographs, illustrations, paintings, and maps, In the Footsteps of Alexander is a colourful, accessible examination of one of history's greatest military leaders.

Introduction

In 336 BCE, Philip II of Macedon, the man Greek historian Diodorus Siculus called ‘the greatest of the kings in Europe’, was assassinated, ostensibly by internal enemies, having united the ever-belligerent Greek city-states (with the exception of Sparta) under his leadership. He was preparing to undertake a bold war on Achaemenid Persia, to avenge at long last the sacrilege that Xerxes (r. 486–465 BCE) had wrought upon the Greeks and their temples a century and a half earlier (Diodorus XVI.95.1). The League of Corinth, the coalition of allied Greek powers, had conferred upon Philip the title of strategos (‘supreme commander’) and given him unlimited power to lead an invasion of Asia and Persia’s mighty empire. But, when Philip fell under the blade of Pausanias, a member of his own royal bodyguard, in the autumn of 336, leadership of the impending Persian campaign passed to his 20-year-old son, Alexander, and the course of Western history was likely changed significantly as a result.

The young Alexander was no novice on the battlefield. He had commanded Philip’s left flank at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE at which the Macedonians (and their Thessalian allies) defeated an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes to become the effective masters of Greece. Alexander was said to have broken the lines of the Theban ‘Sacred Band’. Numbering around 300, the Sacred Band was made up of pairs of male lovers, bound together by personal affection, loyalty to one another and the honour of their city-state. They had defeated the mighty Spartans decisively at Leuctra in 371, but they were no match for the then 18-year-old Alexander, who seemed to possess an uncanny, natural gift for finding the precise moment and place to launch a decisive assault against the enemy. Even at this early stage in his career, he led his troops personally; he took exactly the same risks that he asked of them.

Bust of Philip II, King of Macedon (r. 359–336 BCE), father of Alexander.

A Wealthy Kingdom

But the story of Alexander begins before Chaeronea. It begins in and with Macedon, the fertile, timber-rich region north of Thessaly (and the Greek city-states), into which flows the Haliacmon and Axios rivers. The political boundaries of the ‘kingdom of Macedon’ – that is the Macedonian ‘state’ that, ruled by Philip’s Argead Dynasty, came to dominate first the Balkans and, thereafter, the Greek city-states to the south – shifted throughout antiquity, but, topographically, the area under control of the Macedonians was a roughly uniform circuit of mountainous highlands that enclosed river basins and fertile plains. By the standards of central and southern Greece, Macedon was a land replete with natural resources. Generous rainfall coupled with flowing rivers, abundant timber forests and significant reserves of precious metals helped not only to make Macedon independent and self-sustaining, but made the Macedonian kings desirable, even necessary, trading partners for the Greek city-states. The Athenians, in particular, needed Macedonian timber to construct the triremes that would become so critical to the Greek defence against Persia in the early fifth century BCE and to the rise of Athens’ naval-based empire in the latter. The wily Perdiccas II (r. 448–413 BCE), king of Macedon during much of the Peloponnesian War, had managed, by alternating alliances with Athens and Sparta, to guarantee Athenian dependence on Macedonian timber along with a nearly unending influx of Athenian silver in exchange for it. Philip II’s expansion of Macedon’s political boundaries in 356 BCE brought the rich veins of silver and gold from the mines of Mt. Pangaeum into the Macedonian orbit, providing yet another boost to the kingdom’s already robust royal economy. The ornately-adorned Macedonian royal tombs unearthed at Vergina (ancient Aegae, Macedon’s first royal capital) provide indisputable evidence that the kings of Macedon had become very rich indeed in the course of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. At the height of his powers, in the greater Mediterranean world, Philip’s wealth would have been matched only by that of the Great King of Persia. It was the Macedonian royal house’s significant wealth and resources that allowed the kings to engage in a delicately non-committal, diplomatic dance with Greece’s main warring powers – Athens, Sparta and Thebes – for nearly a century and a half as they weakened one another to Macedon’s ultimate benefit.

‘Xerxes at the Hellespont’ by Jean Adrien Guignet. Xerxes set out in 480 BCE with a fleet and army which Herodotus estimated was roughly one million strong.

Gold larnax or small coffin designed to hold human remains (either cremated or bent into position). This elaborately-ornamented larnax was unearthed at Vergina (in ancient Macedon) and may have contained the remains of Philip II himself. It bears a decorative sun, possibly a symbol of Philip’s Argead Dynasty or a nod to Zeus-Helios, master of Olympus and god of the firmament.

Greeks or Non-Greeks?

Scholars have long sought in vain to answer definitively the question of whether or not the Macedonians can properly be characterized as ‘Greek’. Were they a tribal people akin to the Dorians who migrated into and settled on the Greek mainland in perhaps the twelfth century BCE, the future Macedonians choosing instead to remain in the highland regions of the extreme north? Were they an indigenous Balkan people more closely related to the neighbouring Illyrians and Thracians? Could their ancestors have been wandering Mycenaeans, Homeric Agamemnons displaced by the Dorians and settling, bent but not broken, in the timber-laden north in the hopes of regaining their footing there? The history of early Macedon is shadowy indeed. All of the above remain mere hypotheses, intelligent guesses, but guesses nonetheless. There is such scant evidence of the Macedonians’ original language that it is, in fact, impossible to say with any certainty what Macedonian ethnicity was. Furthermore, early Macedon’s archaeological record (c. 1200–650 BCE) is so spotty that definitive evidence of even permanent settlement has not yet been found and precious early tomb finds are devoid of inscriptions that could reveal whether the Macedonians were using a language separate from Greek.

The ruins of ancient Aegae (modern Vergina), Macedon’s first royal capital.

It is at least possible that, when the Macedonians proper do emerge into the light of history around the middle of the seventh century BCE, they could claim some relationship, if not direct descent, from Greeks of the northwestern mainland. The house of Philip II traced its roots to Argos (hence, ‘Argead’) and to the greatest of the Greeks’ heroes, Heracles, although there is no firm linguistic or archaeological evidence to support Herodotus’ report that the first Argead king, Perdiccas I, had migrated north to Macedon from Argos near the turn of the eighth century BCE (Histories 8.137–139). The archaic poet Hesiod claimed that Zeus had a son named Makednon (whose name means ‘tall’) who ‘rejoicing in horses’ dwelt around Pieria and Mount Olympus (Catalogue of Women, frag. 3), from whom the Macedonians possibly took their name, although some scholars have argued that a Makedones (a ‘Macedonian’) could simply refer to a ‘highlander’ and not, specifically, a ‘son of Makednon’. Indeed, Mount Olympus, the mythic abode of the Greeks’ highest gods (and Greece’s highest peak) towered above the plain of Macedon in the Pierian range that divided Macedon from Thessaly to the south. The first Argead capital, Aegae, practically lay at the foot of it.

Mount Olympus, on the border of Thessaly and Macedon. At some 2,917 metres (9,570 ft), it is Greece’s highest peak, where the ancients believed the gods resided.

But despite these and other fleeting connections, real or invented, to Greek culture and lore, we cannot definitively label the Macedonians as ‘Greeks’. The southern Greeks certainly did not view them in that regard. The Greeks were exclusivist by nature, as was their preferred system of government, the polis (‘city-state’). Indeed, inhabitants of the Greek city-states saw the Macedonians as uncouth, backwater barbaroi (‘barbarians’), foreigners, as distinctively ‘other’ and lesser than themselves. The attempts of Macedonian kings like Alexander I (r. c. 498–454 BCE), who took the nickname ‘the Philhellene’ (‘fond of the Greek’), to ingratiate himself with the Greeks of the south demonstrate a clear distinction between the two peoples. Further, there is evidence that there did exist a unique Macedonian language, or at least dialect, as ancient sources employ a Greek verb, Makedonisti, which means something along the lines of ‘to speak in the Macedonian manner’. One way or another, the ‘highlanders’ from north of Greece did not sound quite like their southern neighbours. There is, however, no doubt that, by the end of the fifth century BCE, standard Attic Greek, even if tinged with a Macedonian brogue, had become the language of the Macedonian court, whether for personal or official correspondence.

Archelaus I, King of Macedon (r. 413–399 BCE). Archelaus was said to have been a man of culture and great lover of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.10.2015 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Landscape History | Landscape History |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Vor- und Frühgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Altertum / Antike | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Alexander • Darius • Egypt • Persia • Philip • Ptolemy |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78274-186-0 / 1782741860 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78274-186-2 / 9781782741862 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 42,3 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich