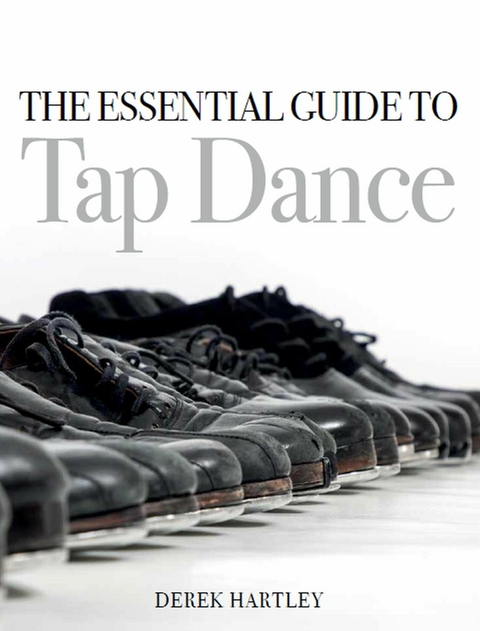

The Essential Guide to Tap Dance (eBook)

144 Seiten

Crowood (Verlag)

978-1-78500-390-5 (ISBN)

Derek Hartley is an international authority on tap dancing, with over thirty-five years' experience as a professional dancer, choreographer and teacher. He has earned a glowing reputation for innovative work in film, television and theatre world-wide, and is a leading lecturer in theatre arts, choreography, jazz and tap history. Derek has taught at many of the UK's major dance schools, including Bird College, London Studio, the Sylvia Young Theatre School and Pineapple Dance Studios, where he still teaches.

CHAPTER 1

THE HISTORY AND CULTURE OF TAP DANCE

The historical and social phenomenon of Jazz dance – which we will establish includes tap dance as the first jazz dance – is so wide reaching that Marshall and Stearns, authors of the greatly acclaimed Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance, published in 1968, reflected that: ‘The subject is so vast that after six years of research, we gave up all idea of telling the whole story.’ This is the book for the serious student of the dance, but especially of jazz dancing, and the authors map out the route from the very beginning of dancing to music in a jazz form – see following chapter.

In The Book of Dance, written in 1963, Agnes De Mille is quoted as saying: ‘Since 1850 there has been little change in Europe. All further innovation comes from the United States, Cuba or South America, and all broke with previous tradition. Africa is the chief source of these new music innovations.’

In thinking about the beginning of the beat and what happened to it (and thus about rhythm), we can see that it has no connection to those latterly added European elements such as separating the toe and heel, as in ballet or Irish or Scottish dance, or in the carriage of the upper body in the waltz, for example. Rather the beginning of the beat has as its base a flat-footed and stamping essential, and it uses a gliding and a dragging element.

Most important is the propulsive rhythm of the African dancer and ‘the uniquely racial rhythm of the Negro’ (John Martin in The Dance, included by Marshall and Stearns). The African style brings a difference in its crouching, skipping, springing and jumping – hardly European in that era of the nineteenth century. Of course, the absolute addition and the revolutionary essential is in the fact that it is syncopated, whereby the use of stress on notes is freer and impulsive.

Syncopation is the start of tap dancing… adding the feet sounds to the fusing together of joyful clapping, shuffling and calling out to a rhythm that swings and has syncopation. This new wave had to travel from the nations of Africa, however, and there were various routes responsible at that time to facilitate its spread, not least the slave trade to America. Tap teacher Gerry Ames in his The Book of Tap, written in 1977, states what has since become common knowledge:

What we now recognise as American tap dancing had its beginning when the start of the slave trade in the new World brought about the first collision of European and African cultures. During the long sea voyage from Africa to the Americas, the newly captive slaves were brought up on deck to exercise and entertain the crew.

The Africans first applied their rhythms to European dances on the plantations. As on shipboard the white masters of the Old South made their plantation slaves perform for them … (at which they used the… opportunity to parody the white folks’ grand march of the Minuet). Later slave dances copied the stiff bodies and the flying feet of the Irish jig dancers from the North.

This rough and loose beginning gradually became more civilized and formalized as a thing to learn and enjoy, and therefore to spread. The early and great jazz musicians such as Duke Ellington, Eubie Blake and King Oliver would help this spread by their music, descended as they themselves were from the slave era. Around 1900 and beyond, this music was called ‘blues’, depicting the social circumstances of the African in the New World called America. Before this it was called ‘Race’ music. The words ‘rhythm and blues’ and then ‘jazz’ were natural progressions.

Moving forwards from this time to the late 1920s, the predominant jazz idiom was called ‘Ragtime’, previously ‘Rag’, because it was uneven and impromptu. In other words, ragged and ‘in ragged time’ became Ragtime, and an extremely popular and revolutionary music style was born. African American ragtime musicians such as Scott Joplin, Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller were among those who were influential at this time, and who influenced the tap dancers, too.

A well worn pair of shoes, once moulded to the feet, gives the dancer confidence and a feeling of superiority in producing rhythms. He will feel he can go beyond thinking and just perform.

In the hot summers in the major cities such as New York, New Orleans and Chicago, it is not hard to imagine this fresh and vibrant sound pouring on to the streets through the thousands of open windows and forming the ‘jazz age’, with hundreds of performers, writers, singers and dancers travelling all over America. Clearly, jazz and tap grew up alongside each other on these streets and in hundreds of towns and cities, and still do so to this day, even though both have diversified radically since.

In other parts of the world other patterns of social and financial circumstance were also playing their part in the development of tap dance. In the harsh working conditions of the Yorkshire mill towns and the Lancashire cotton factories, the machinery in these workplaces and the sound of clogs on the feet of the workers themselves would help to instil this feeling of rhythm in the body of the individual. The sound of the dancer was emerging from diverse parts of the world, and from adversity itself a new dance of the folk was on the way.

The jazz dancer of those times was the street performer, the itinerant who could move and gyrate enough to earn pennies and dimes thrown into his hat, just by foot sounds, hip movements and shaking! These dancers were called shoe dancers, not yet tap dancers, and would get away with having little sound from their feet by using the body itself. In this way of street popular expression, dancing was a sort of social glue that would help with all the problems that integration by so many cultures brought to the shores of the continent. The dancers would inevitably become more innovative, and everyone would steal steps and moves, which would also progress tap dance itself. When the taps were eventually added – by nailing coins to shoes, or just using the nail heads themselves – tap dance would be officially born.

The kind of music that is ideal for tap dancers in today’s era is largely dependent on the dancer’s own perception and their intrinsic feel for what they hear. We don’t actually need music as such because percussion stands alone in the definition of music. To tap dance is to make music anyway, but perhaps what we do need to watch out for is timing. If we believe, as I do, that tap is the original jazz dance and is inextricably linked to this kind of music by its timing measures, phrasing and syncopation, then we have to admit that as timing exists in most jazz music, it is therefore probably best to tap to jazz.

As a teacher, I have learned that people love to know when a step or figure starts and when it finishes, as well as how it gets there! I am quite certain the best way to understand tap dance is when it makes use of music. For many, adding music to the learned technique is the final nail in the construction of the ship, because the joy lies in being able to combine what they are doing with what they are hearing. This togetherness of feeling is what we love to have in our dancing, and that is why in any show – whether in a class with children banging away, or in a super-charged number on the stage of a professional college – the sound of tap dancing to music is usually the winning combination.

It does not need to be straight jazz, but it benefits from the jazz-type structure of the 4/4, which forms the basis for most Western music we hear today in almost everything we listen to. Earlier I intimated that percussion is music for the soul and from the soul, and we only need a metronomic machine-like soundtrack to dance to; but it’s the structure we are most comfortable with. I think it all stems from the human need for structure and form. The lovely predictability of the nursery rhyme is a perfect example of structure when it goes as follows (sing this to Hickory Dickory Dock, if you know that rhyme):

diddle de diddle de dah;

de dah de dah de dah:

de diddle de dah, de diddle de dah;

diddle de diddle de dah.

It has a roundness that helps, and we latch on to that fact. It helps us understand the rhythm and enjoy the syncopation and the cleverness of the mind that has conquered the coordination of head and feet. Now… that’s tap dance!

So, is tap dance an American dance? Or a dance from all over the world? The truth is, it is both of these: a new dance formed in a New World from the Old World of Europe and beyond by the people of that Old World and beyond. What makes it American and thus unique is where it was formed: the clash of these cultures in the towns and cities and on the farms, which produced an entirely new thing. It is, of course, American but with far-ranging influences. Gerry Ames again in The Book of Tap states that:

Most ethnic folk dances contain elements that can be likened to tap, but tap dancing as we know it today is a uniquely American product…with identifiable roots in certain dances in Europe and Africa and, like many American creations, the result of a blending of cultures – a melting pot of old world tradition with new world imagination that is expressed out of American spirit.

The jazz era was ‘new’ and the fashions were all new, as were working practices and social mores after the ending of World War I, and excitement was everywhere – ideal for producing so much of everything. America still retains this exciting quality, and we think of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 138 colour photographs 3 black & white photographs 5 line artworks |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Tanzen / Tanzsport | |

| Schlagworte | choreography • dancer • Fred Astaire • Improvisation • music • Oxfords • paddle • Performance • Pick-up • Production • Rhythm • Routine • Shuffle • stage • syncopation • tap shoes |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78500-390-9 / 1785003909 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78500-390-5 / 9781785003905 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich