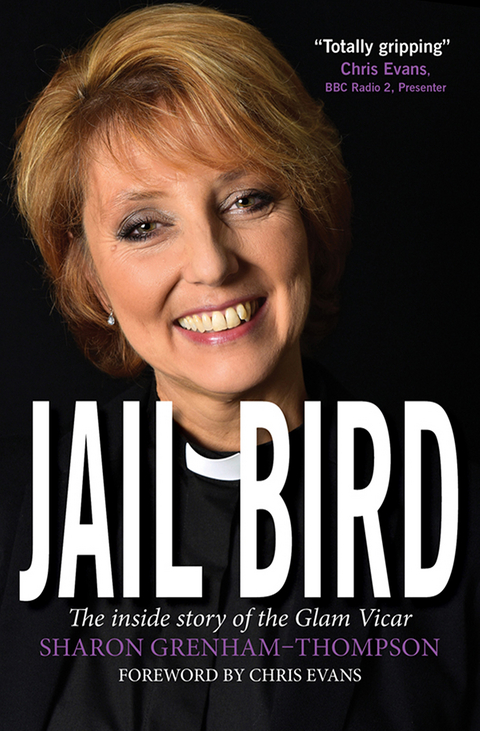

Jail Bird (eBook)

208 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-7459-6878-0 (ISBN)

CHAPTER 1

TO BE A PILGRIM

It was a sunny March day in the late 1970s. As the car pulled up on the gravel drive, I looked out of the window at the grand building filling the view. It was made of pale stone, set against a clear blue sky, with a semicircular stone staircase leading up to a set of double doors. To the right was a terrace, covered in ivy, with a gate leading through to another terrace, and then extensive playing fields, tennis courts, and a long avenue of lime trees. To the left were more buildings – huge, brown brick, with long vertical windows suggesting an enormous hall above the first floor level, and smaller, arched windows at ground level, looking a bit like the nether regions of a London station.

There were cars everywhere (a lot posher than ours, I noted immediately) and a stream of girls, all ages and sizes, but all dressed in the odd combination of brown and blue that eventually became my much-loathed attire for the next half decade. This was the North London Collegiate School for Girls, and I was about to take the entrance exam.

My family had only flown in from Gibraltar a couple of weeks previously. We’d been posted there since July the year before, and I’d been an army brat. Now my stepfather had changed his post, bringing us back to the UK. I was still missing the friends I’d begun to establish on the Rock, and pretty fed up about having to move again. Since Mum and Dad split up three years ago, and then Mum remarried, it felt like we’d been constantly on the move.

I’d already sat one entrance exam for a different school, and passed easily. Today would give me a comparator. It was certainly bigger; and as the gracious, but to my eyes somewhat intimidating, deputy headmistress took us on a tour, I could see that the facilities were amazing. Good old Dad – I hadn’t really known much about the financial wrangling connected to the divorce, but I did know the upshot was that Dad paid school fees. We weren’t a wealthy or well-connected family by any stretch of the imagination – but my mother’s aspirations, Dad’s hard work, and my rather surprising intellectual sharpness proved to be a pretty lucky combination.

I passed the Maths, English, and French papers, and the interview, despite being pulled up for not being able to spell “separately” (that one still makes me anxious). A couple of weeks later, at the start of the summer term, I joined the brown-and-blue clad young ladies and once again began the task of fitting in and finding out.

I’m not sure whether I distinguished myself or blotted my copybook on that first day – probably both, depending on whether the onlooker was a teacher or a classmate. Having been brought to class after morning registration, introduced to the thirty or so faces that greeted me as a new girl, and then left to it, I started off confidently enough.

“Have you just moved?”

“Where are you from?”

“Why are you starting late?”

I parried the barrage of questions, my recent provenance from the Med being deemed interesting enough to earn me the offer of sweets, a flurry of introductions, and a promise to show me round at break-time. It was the next question that my already highly attuned social radar twitched at.

“What does your father do?”

“Oh,” I replied airily, aware that this could make or break me in what was quite obviously a privileged circle and deciding not to explain the stepfather thing, “he used to be in the army, but since we moved he’s going into business or something.” And with that I turned the questions around, asking about the form teacher, the rules, anything I could think of to deflect the attention away, however kindly meant. Although as an adult I was later to learn just how varied and far from privileged many of my contemporaries were, it was still a long time before I confessed to any of my peers the complications and confusions of my family life.

The morning came and went, lunch in a vast dining hall – the place with the railway arch windows – and back to classroom Upper Three Thirteen, to await the afternoon’s lessons. Rosie had a tennis ball, and three of us began a game of catch around the room, standing on the wooden-lidded desks and bouncing the ball off the desks in between. Several others gathered, and soon we were all laughing, and I felt as if I’d been there months, not hours. Buoyed up, I gave the ball a bit of a flourish as I threw it.

Bad idea. I don’t think I’ve ever bowled a spin ball since, but I certainly did that day. Narrowly missing Rosie, it hit the corner of a desk, careened upwards, and hit the ceramic lightshade hanging in the centre of the room. Shattering it into a thousand glittering pieces. On. My. First. Day.

With impeccable timing, the form teacher bustled through the door, and as she hit the stunned silence, she visibly recoiled.

I looked at Rosie. Who gaped at me. Alison, Sarah, Jane – all their eyes were wide; you could practically see the panicked thoughts racing across their minds.

“What do you think you are doing?” Mrs L.’s voice unfroze the scene.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered. “It was me; it was an accident.”

Dispatched to find a dustpan and brush, I was saved by my status of “new girl”, and into the bargain somehow seemed to have passed an initiation test with my classmates. I would spend most of the next six years with them, and in some ways they became the family I would often feel I lacked. My best friend was one of those classmates, and she and I have grown up and grown older together, our kids more like cousins than just buddies. Thanks to reunions and Facebook, several of us have stayed in sporadic touch. We’ve seen tragedies and success, love and loss, but put us together and we’re giggling teenagers again.

I wasn’t a classic naughty girl at school, but it’s probably true to say my independent, free-spirited streak got me into trouble on more than one occasion. I would meet local boys at the bottom of the vast playing fields, which were out of bounds, traipsing across the local park at lunchtime with my friend to try out cigarettes, and flout the school uniform rules as often as I could. It wasn’t much of a teenage rebellion – I was always too terrified of being found out and parents being summoned – but I lived with tight controls at home, and high expectations at school. The steam had to escape somewhere. In fact, it wasn’t really until my university years that things threatened to get out of hand – so for now I pushed the boundaries just far enough to get away with it, and thrived in the creative swirl of possibilities presented to me in my protected suburban world.

The headmistress at the time was nowhere near as scary in manner as her deputy, but she was the kind of lady (and I use that word advisedly) whom you really did not want to let down. She was elegant and very clever, quite elderly (so it seemed at the time – she was only in her fifties!), softly spoken, but most definitely in charge. Once when I was sent to her for yet another minor misdemeanour, she quite undid me, not by scolding, but by being disappointed. She epitomized for me the kind of strong, magnetic woman I wanted to be. Maybe there are echoes of her in my character now, but I’m nowhere near as calm and poised.

She was also a woman with a strong Christian faith and a vivid sense of social responsibility. She was carrying on a long-established tradition, set down by the great Victorian educator Frances Mary Buss, the school’s founder. It might be couched in different terms now, and I know that private schools are seen by many as a cause for scorn, but the view was that we were privileged members of society, and therefore it was our duty to use that privilege for the good of others. So we would host an annual Christmas party for a local home for the severely disabled, there would be numerous charity collections and events through the year, and in the sixth form we were all expected to undertake voluntary work in one form or another. I helped out at a local old folks’ home with some of my classmates, singing songs, chatting, listening. It probably was a bit patronizing, but it did establish in me a sense of obligation, and of how even small gestures could make a big difference to one person. I remember one occasion when representatives from the John Groom’s charity laid on an event whereby we could all experience just a fraction of the physical challenges posed by being in a wheelchair. As we struggled our way around the netball court, trying to pick up small items with a grabber, I had my eyes opened. All part of an education in empathy I suppose, although the Christian ethos was little more than a generalized moral framework for me at the time.

We were of an era when there was still a Christian assembly every day, although the sizeable group of Jewish pupils had a separate Jewish assembly in the gym. It was all very mysterious to us Gentile girls, especially as we were banned from attending.

Assembly usually included a music student playing something worthy on the violin or organ, followed by a rousing hymn, presided over by the large and enthusiastic Miss G., a former opera singer. We were encouraged to enunciate correctly:

“It’s ‘We plough the fields and scetter’, gels, not ‘sca-a-atter.’”

Then the Head would read...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.11.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7459-6878-3 / 0745968783 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7459-6878-0 / 9780745968780 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich