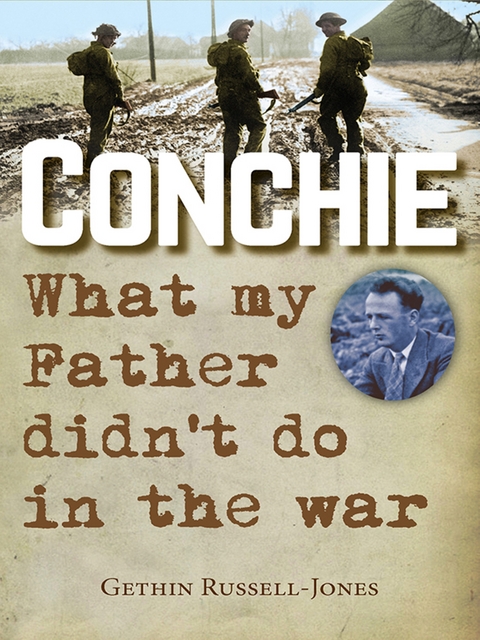

Conchie (eBook)

240 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-7459-6855-1 (ISBN)

While Gethin's mother spent most of the Second World War cracking German codes at Bletchley Park, his father was a conscientious objector.As he grew up, and his mother maintained her Government-imposed silence on what she had been doing, Gethin's father was voluble on his pacifism, and Gethin dreaded the question 'What did your father do in the War?' The answer 'Nothing' seemed shameful.Now, with his mother's story out in print, he sets off to find out why his father took the stance he did, the roots of the tradition of conscientious objection in the Welsh valleys, and how the family felt about the decision and the shame it brought.

CHAPTER 2

Conchie

My dad, John Russell-Jones, was a CO (or Conchie as they were usually called) in World War Two. I want to open the sealed envelope of my father’s account, get behind the story, and find the 21-year-old young man who was prepared to face such opposition. This quest is given added bite by the looming centenary of an Act of Parliament that made my father’s dissent, and that of many thousands like him, possible.

As World War One went on, and newspapers reported the thousands of casualties suffered by the armed forces, and mutilated soldiers returned home, Britain increasingly lost its appetite for glory on the field of battle. Widely circulating accounts of chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gassing in the trenches added to the public’s distaste for military service. Whereas nearly 1.5 million men had volunteered during the first six months of the war, numbers had dropped dramatically by 1915, and continued to do so.

It was the day that saw the death of the happy amateur, the gentleman volunteer. After two years of warfare with Germany, the numbers of men enlisting to fight for king and empire were dwindling. No longer able to resist conscription, Prime Minister Asquith relented and on 2 March 1916 the Military Service Act came into force, having been passed in January. Much to the chagrin of the Liberal Party, Labour Party, and Trades Union Congress, the new law represented the failure of several voluntary schemes. Military service was now compulsory for all men between the ages of eighteen and forty-one, although there were a number of exempt categories: married men, widowers with children, men in reserved occupations, and clergy.

And a new exemption was created: that of the conscientious objector. Virtually alone on the world stage, Britain allowed men to appeal against conscription on the grounds of conscience. A handful of nations gave exemptions to Mennonites and Quakers but none recognized the right to dissent on broader religious and moral grounds. So this was a groundbreaking moment in British legal history on two counts; conscription was introduced for the first time, as was the right to resist it.

But still the numbers enlisting were not sufficient for the war effort, so the Act was revised four months later. All men previously declared medically unfit for service were to be re-examined, and retired servicemen were also included within its provisions. In 1917 the Act was again changed: servicemen who had left military service due to ill health were to be re-examined, as were Home Service Territorials, and the list of reserved occupations was shortened.

But still they wouldn’t come and so the legal stick was further strengthened in January 1918 with further amendments. Various occupational and other exemptions were quashed, and yet the war needed far greater numbers. So in April 1918, with the war now reaching its apex and the burial grounds of the Western Front filling with the fallen dead, the parameters were dramatically changed. Men aged between seventeen and fifty-one were now conscripted and for the first time this extended to Ireland (although the policy was never implemented there), the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man.

Three million men volunteered for military service between August 1914 and when the first version of the Military Service Act came into force in 1916. A further 2.3 million men were conscripted as a result of legal coercion.

Globally, over 17 million men died in the Great War and a further 37 million were wounded. At least 887,711 United Kingdom and Colonies military personnel were killed and when civilian deaths were added, the UK casualty figure rose to over a million.

Conscription was abolished in 1919 but reintroduced in May 1939 before the outbreak of war with Germany. The Military Training Act required all men aged twenty and twenty-one to be called up for military duty, although this was superseded in September when the National Service (Armed Forces) Act came into force. All men aged between eighteen and forty were required to sign up for duty and, after extensive loss of life, this age limit was extended to fifty-one at the end of 1941. From 1941 onwards and for the first time in the history of the British Isles, single women aged twenty to thirty were also compelled to perform non-combatant duties.

All these legislative measures recognized the rights of conscientious objectors (COs) and prescribed the means by which their appeals could be heard and judged. In the First World War there were 16,000 registered Conchies and there were 61,000 in World War Two. And it is not unfair to say that as a group they were generally reviled and misunderstood. Many of the COs in both wars objected on the basis of religious conviction, but others said no for political and moral reasons.

I’m going to try and find out why my father followed the voice of conscience instead of the prime minister’s.

My dad was not a killer; that much I do know. However, even though his war passed without salute, parade, or medal he served in a different way: protecting others without lifting a rifle. Not so my mother. Her world war came to an end sometime in the 1990s; in that decade she broke her long silence and began to break the hold of the Official Secrets Act. Initially a trickle and finally as a broken cataract, she spoke of Bletchley Park and her part in Hitler’s downfall.

Whereas my mother kept mum for over a generation and then spoke of nothing but the war for the last ten years of her life, my father was different. His running commentary started as Germany invaded Poland, gathered pace during his student years, and then petered out in his later adult life.

Within the confines of home, he could sometimes be volubly critical of war, always advocating a more Christian perspective as he saw it. His pacifism was bundled together with republicanism, socialism, and a general dislike of any kind of privilege. In public, however, he was a model of diplomacy; except on one very public occasion when he cocked a snook at the establishment.

I need to find out why my father refused to fight in the Second World War, especially as this decision heaped criticism on him and his parents. Not unlike him, I’ve largely kept quiet about his Conchie status outside the home. So this quest will also probe my own reactions. Why have I kept so silent? Am I embarrassed, ashamed even? From a young age I knew that Dad was a pacifist; it’s my reaction that’s the problem. But there’s another aspect to all this: whereas I can recall his pacifist leanings, not all my siblings can. This is why tracing any family’s narrative is more or less doomed to be a two-headed fact and myth creation. So what follows is my take on my dad’s dissent; I cannot claim it as the authorized version.

The publication of my book about my mother’s wartime heroism, My Secret Life in Hut Six, and the seventy-fifth anniversary of the D-Day landings in 2014 have forced me to look again at my father’s legacy of non-violence. On the day of the seventy-fifth anniversary, the TV schedules were filled with men of his generation: grey, distinguished, and lauded for their courage. There was even the story of 89-year-old Bernard Jordan, a World War Two veteran who escaped from his care home on the south coast of England and travelled to Normandy to be part of the celebrations. Without a formal invite and without the home’s permission, he took a ferry to France and became an overnight national treasure.

All the men were of my father’s vintage, each with a story to tell. Whiskery, grey, and beret-capped, they looked back to a time when they took on the world. Like him, many of them became fathers and grandfathers and had known long professional lives. But they had faced a terrifying rain of bullets, bombs, grenades, and landmines and somehow survived. They came also to remember fallen comrades whose bodies now lie in foreign soil. Not so with my father. No stories of adventure, fear, or tedium; his world war was a very personal affair.

His legacy of pacifism sits uneasily with me and I’d like to know why he chose not to bear arms against the Germans and their allies. During my teenage years when teachers and other boys spoke openly of wartime connections, I kept my counsel. In more recent times my disquiet over the pacifism of my now dead father has grown. So this book is an investigation on two levels. I’m searching for clues about my father’s decision to stand up and not be counted as a soldier. I also want to understand and deal with my own warring feelings.

There have been times when I have admired his lonely, even heroic bravery. Not going along with popular opinion and having a dissenting voice is a deeply uncomfortable thing to do, especially when your actions are perceived as unpatriotic and weak. That takes a certain kind of courage. Particularly when I consider that my father was socially compliant, reserved, and conservative (with a small “c”).

I remember him as an old man: suited, aged, and blind. Quiet, dignified, he bore his sightlessness with great stoicism. Firm, often dogmatic, he was yet willing to find common ground with others. I want to reach back to his earlier outspoken bachelor years, and get beyond the guarded man, often suspicious of others, anxious about losing his reputation and messing it all up. I need to travel back to another age where he swam against the prevailing tide. I’m looking for a stubborn hothead; at least that’s the image in my mind. I need to peel back the layers, see beyond the various...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.3.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | german codes • Second World War |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7459-6855-4 / 0745968554 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7459-6855-1 / 9780745968551 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich