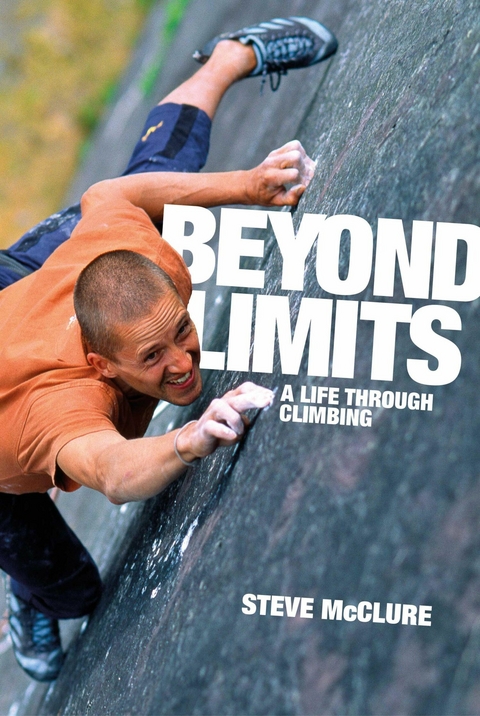

Beyond Limits (eBook)

Vertebrate Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-910240-20-5 (ISBN)

Beyond Limits is the autobiography of Steve McClure, one of the world's top rock climbers. From his childhood encounters with the sandstone outcrops of the North York Moors right up to his cutting-edge first ascents such as Overshadow (F9a+) at Malham and Mutation (F9a) at Raven Tor, Steve explores his deep passion for climbing and how it has dictated and shaped his life. Introduced to climbing by his parents at an early age, Steve quickly progressed as a climber, developing a fascination with movement and technical difficulty. Rapidly reaching a high standard, Steve became torn between the desire to climb increasingly bold routes and his hesitant approach to danger, with a series of close calls forcing him to seriously question his motivations. Searching for a balance between risk and reward, he struggled to find his place as a climber. Having dropped out of the scene, a chance encounter led to his discovery of sport climbing. Free from fear, Steve plunged headlong into this new style and surged through the grades. Pushing everything else aside, he allowed climbing to take over his life. He reached world-class levels of performance, but once again found himself searching for a balance between risk and reward, yet this time the risk was of losing what is truly important in life. As he searches for what really makes him tick, his climbing comes full circle and returns to where it started - climbing for the love of it. Beyond Limits is the story of a climber and his obsessive exploration of the sport, of finding a true passion, taking it to the limits and attempting to delicately balance this passion against other aspects of life to give the greatest rewards.

– Chapter Two –

Balance Point

Fifteen years old and invincible. Bounding up the easy starting moves there was no thought of failure, potential to reverse was an option, but I’d climbed this route before, a few times, and never fallen. So I was going up. The protection was poor, so this time I’d dumped the rope and harness, the freedom of soloing without any equipment was so appropriate for the style of climbing on the North York Moors; short and technical. Stopping briefly to chalk my fingers I relaxed on good holds and soaked up the panoramic view from my lofty position high on the Wainstones. Hills and countryside extended before me in a 180-degree spread, gentle rolling moors shimmering in the midday summer sun, the smell of the heather and bracken and warm sandstone adding to the sense of presence. To one side the rugged landscape disappeared off into rarely explored moorland, to the other, softening gradients gradually flattened into farmland, eventually stretching to the North Sea. In the distance chimneys and towers punctured the horizon; an orange flare from one, steam and smoke from others. The huge chemical works of ICI were visible, but too distant to cause offence. In a way they added comfort: my dad was there, at work in the vast factory as he was every week day and as he had been for thirty years. Just out of view was the small town in which we lived. My mum would be at home, passing time with my younger brother in the school holidays, reading, or maybe making something. They’d be wondering what I was up to, having set off first thing that morning on my mountain bike with a huge rucksack full of junk, my vague plan being to spend a day or two out climbing and sleeping on the moors, alone.

The Wainstones is a cliff typical of rock climbing on the North York Moors, good quality sandstone with smooth ironstone intrusions that reward us with sharp incut finger edges. At 10 metres high I’d be up and down this route in minutes and on to the next. I could tick the whole crag in a few hours and that was my aim, except for a few desperates, to cover a lot of ground, to climb a load of routes. In the last year climbing had taken over my life. Before then, when I was really just a kid, I had dabbled with it, playing with climbing like a toy when interest arose, until suddenly all my other toys had fallen aside. What was left was a desire, bordering on a need. I climbed a lot, often alone, usually traversing low to the ground at the base of the cliff or on the scattered boulders, but sometimes higher, challenging myself mentally as well as physically on longer routes where failure was not an option. But I understood about risk. I understood it as a teenager does, which basically means I didn’t have a clue.

Bringing my attention back to the rock I swung into steep terrain, the rocky ground below suddenly making its presence felt. Moving carefully now as the climbing difficulty increased, I slowed my pace, concentrating on precision – but as with every other day I felt invincible; I was in control. Setting up for the crux reach, the distance between the holds felt longer than usual and there was a slight creep of my fingers on the tiny edges. For sure this was a big move, way out of character for HVS (now upgraded to E3) but it just required balance, exact positioning of the body using specific holds carefully chosen from the multitude of options. At my height, foot placements on the big ledges had to be avoided, as they were all in the wrong place. Instead each toe was carefully and accurately placed on poor holds, sloping and barely bigger than a postage stamp. This required confidence in friction, with feet as far out from the rock face as possible and a big drop underneath my heels, but in this position the centre of gravity was in a friendlier orientation. Push down on the toes now, but not too hard. Hips turned in and chin to the wall and then an ever so slight ‘udge’ for the huge pocket handhold that is mockingly just out of reach. For a taller climber this should be easy, and even for the short it’s no problem, so long as you commit, because once you go for it there is no going back, make the move and grab the hold or peel off backwards into the void below. The lack of rope insisted that I pulled harder and stretched further, looking for a ‘static’ method, but there was none to be found, not at 169 centimetres tall, and as I approached my target and my fingers crept up the wall, I felt the balance point begin to tip. Eyeing the handhold with 100 per cent focus I chose my moment, committed to the movement and sprung the mere 10 centimetres upwards to bury my hand in the mother of all jugs. All four fingers positioned perfectly on the incut ironstone pocket handhold, but, with absolutely no warning, my hand shot outwards only to stop right on the lip, only the very tip of my middle finger remaining in contact. Battling to stay on, I pivoted wildly to end up facing outwards with my right arm high above my head, my lone fingertip preventing me from the 8-metre drop into which I now stared. Facing out I prepared for the drop as if I’d already fallen, but somehow my arms and finger operated independently from my brain, hanging on without direction, following their own sense of self preservation. Movement ceased and, without breathing, I slowly extricated myself, carefully unfolding my position to avoid awkward loading. What happened? The pocket was full of water, warmed by the sun so I couldn’t even feel it, but rendering the ironstone as slippery as ice. Topping out I was shaken, but not stirred, as any aspiring action star would like to quote. It was almost a buzz, to have been that close, but close to what? I didn’t know, not yet, my boundaries still undefined through blissful ignorance.

Things had been closer before, in a way. Closer in that I actually fell off. My first leader fall was from an E2. I was twelve years old and my younger brother Chris was eight. It would have been my first Extreme grade route. I set off upwards with a rack of two rigid stem cams and Chris holding the rope with one hand and no belay device. Peeling off the rounded arête with a single cam a metre below my feet I plummeted straight into the rocky ground from 6 metres, possibly saved slightly by the rope, though the only evidence of any fall arrest was the monumental rope burn on Chris’s hand. I got away with that one, the worst part being the massive bollocking that my mum gave me for being such an idiot.

My second leader fall at least employed a suitable belayer, in the form of my dad. This time I had a waist belay, with my end of the rope tied around my skinny waist with a bowline knot. I’d probably top-roped this E3 (now E4) before, but on the lead I tipped backwards off Lemming Slab to be caught by a single and incredibly marginal piece of protection, with most of the metal wedge sticking out from the crack. Apart from the rope burns on my ribs I didn’t suffer at all, though looking back, from a parent’s perspective, my dad almost certainly did.

It’s interesting how it’s usually the young who are the bravest and craziest, with dangerous rock climbing generally being a young person’s game. You’d think it would be the old-timers, with way less to lose in terms of remaining life, who would risk a smash into a jumble of boulders? They are already running out of time and their bodies are shagged anyway. Mostly though, the older you get the more it hurts when you hit the ground and so, peering down between your legs hunting for a comfortable landing zone whilst considering your bad ankle or dodgy hip tends to overwhelm any kind of pleasurable experience. Younger climbers don’t even consider falling off, so hitting the ground doesn’t matter because it isn’t going to happen. Perhaps youngsters simply can’t compute the risks, or haven’t collected enough stuff yet – they have nothing to lose.

Pushing to physical and mental limits in a dangerous situation can be exciting. I’ve been there a few times, but I generally choose my moments carefully, or stray there by accident. In general terms, rock climbing used to be all about risk; that was the perception and that’s how it was portrayed in the climbing press. Climbing and danger were inextricably linked and ‘real’ climbers were only validated if they embraced danger. The further they pushed it, the more distinction they achieved. That wasn’t my game. I took on a level of risk because that’s what I was supposed to do as a climber, but I was never bold, not really. I knew right from the start it was the movement I enjoyed, that’s what gave me the buzz. I’d thrive on the challenge of a difficult section of rock, solving its puzzle either against the clock as my arms burned with lactic, or with repeated attempts over hours or even days. I revelled in the deciphering, analysing what was on offer for hands and feet and piecing together a string of movement over the stone. I guess I was in love with the rock – you have to be really, to enjoy the feel of it under your fingers, the bite of coarse sand against skin and the way a hold asks to be used. I’d solve each puzzle from an analytical point of view: if I pull that way I need to push from the other; for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. The more complex the puzzle, the better it was, with unlikely sequences and the use of non-holds often unlocking a baffling problem. Balancing delicate body positioning and precise foot-work against physical force and hard pulling forms an intoxicating mix, a captivating combination of mind and body working together, taking something from impossible to possible in the most rewarding way. Close to the ground or from the safety of a rope it was easy to become absorbed; it was all fun, an...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.11.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-20-6 / 1910240206 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-20-5 / 9781910240205 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich