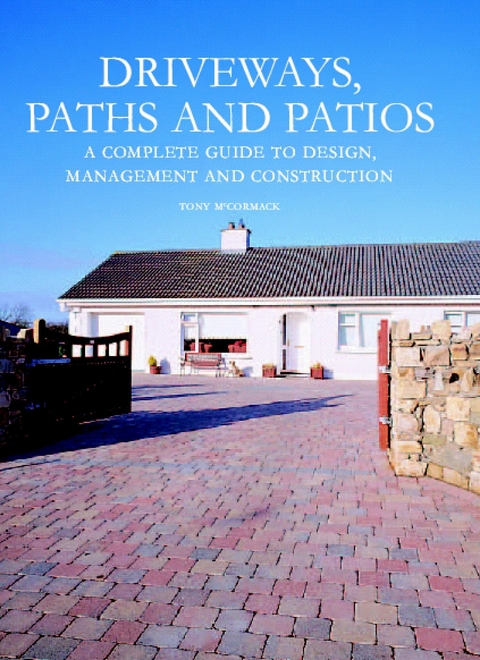

Driveways, Paths and Patios (eBook)

176 Seiten

Crowood (Verlag)

978-1-84797-327-6 (ISBN)

Driveways, paths and patios are an essential part of most properties and this comprehensive book provides a detailed explanation of exactly how they are designed, planned and constructed. Discusses the design of driveways, paths and patios with reference to their planned use, style, size, gradients and special features such as steps, ramps and terraces. Considers the range of materials available including block paving, flags, slabs, setts, cubes, cobbles, loose aggregates, plain & patterned concrete and tarmac. Analyses how to estimate costs and making the choice between the DIY approach and using a professional contractor. Examines the critical issue of drainage. Lays bare the mathematics associated with accurate setting-out and levelling. Describes the range of tools and equipment needed. Details the correct constructions of kerbs and edging and laying methods for flags, block paving and much more.

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Paving

EARLIEST DAYS

Paving is one of the oldest of all the construction trades and has been used by man since long before we bothered to record history. At some unknown point in time, a human being, no less intelligent than ourselves, but living in very different circumstances, decided to improve the trackway he was using, perhaps throwing some dried rushes and twigs over a swampy stretch to help keep dry his poorly shod feet, and so formed the first ‘improved’ path. And maybe he scattered some sand and gravel, collected from a nearby beach or riverbank, on the area directly outside the family shelter, making it safer for children to play and cleaner for the clan to sit out and eat in the open air, and in the process unwittingly created the world’s first patio. We shall never know, but it is a safe bet that others soon imitated the techniques, and word started going around that the bloke from the tribe over the hill was a bit flighty, and was using poor quality gravel or sub-standard rushes.

Pathways were essential to the development of human societies. They linked families and clans, tribes and kingdoms, providing trade routes and the main means of communication. Gathering areas – what we now often call patios – provided places for meeting and eating, locations where tales could be told, knowledge shared and gossip spread, so that much at least has hardly changed.

The earliest paths were ‘improved trackways’. They had come into being naturally, as humans and other animals followed the easiest line through the landscape, skirting around the wettest patches, avoiding impassable obstacles, looking for the gentle gradients, and gradually developing from a stretch of trampled grasses to strips of bare earth or rock, slowly widened as travellers on two legs and four expanded the edges when their feet, paws and hooves sought drier ground. Dry matter would be added to improve the surface, sand, grit, gravel, rushes, leaves, and then someone would place a flattish stone or two, and we had the first flagger!

In the British Isles, some of the paths and trackways of pre-Roman times are still evident in the landscape. The Ridgeway of southern England along with the Icknield Way are, perhaps, the best known, following the higher, drier ground as they weave across the chalk landscape from Salisbury Plain to the Fenlands of East Anglia. Both are thought to have been used for at least 5,000 years and they probably go back much further than that.

Meanwhile, over in continental Europe the Romans took the principles developed in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Sumeria and Greece, developing and refining road-building technology to a new level. The Via Appia linking Rome with Capua is possibly the most famous of all Roman roads and has been dated to 312BC. The Legions had a well-developed strategy of having their cohorts build the roads as they progressed through a territory, continually expanding the Empire and the Pax Romana. Prisoners, slaves or general labourers followed in their wake, carrying out essential maintenance and repairs.

Modern view of the Ridgeway near Uffington Castle, Oxfordshire.

PAVIMENTUM – THE ROMAN COLONIZATION

The Roman colonization of Britain brought a massive upgrade to some of the traditional trackways, but it was the construction of new routes, with their characteristic ‘straight-line’ alignment, that largely ignored topography, that has come to dominate what we now think of as Roman roads. These represented a quantum leap in pavement technology, comparable to the upgrading of a meandering country lane to a modern motorway. Not only were new construction techniques employed, but also a scientific, logical, methodical approach to paving was introduced. Carefully selected and graded materials, construction in definite layers, provision of drainage, and technically-competent setting-out by skilled workers known as agrimensores, all of which contributed to the basis of the modern civil engineering and surveying professions.

Here, for the first time in these islands, a national standard for construction was imposed, and so well-built were these roadways that several survive to this day, and many more established the route for some of our busiest modern highways. The key to the longevity of these pavements, other than military necessity, was the use of a cambered surface, with distinct layers of different materials forming the structure, and the provision of simple yet effective drainage at the edges. Added to these was the routing, which linked major towns and settlements, and so ensured that the roads were used, valued and therefore worth maintaining.

It is easy to be carried away by the progress such roadways represented and to overlook the fact that some of the techniques used would have been transferred to smaller scale projects. If the Fosse Way and Ermine Street were paved, then feeder or tributary roads would have adopted and adapted some of the principles involved, and access tracks to private dwellings and villas would similarly have borrowed some of the techniques. Indeed, it was in public buildings and the homes of the important citizenry that other forms of paving were used to great effect.

Busy town centres had paved footways and streets, with elementary separation for pedestrians and vehicles. These pavings were mostly of riven flagstones, blocks of dressed or pitched stone laid as setts, or loose gravelled surfacing, although there is a suggestion that timber may have been used in some situations – it’s unlikely to have been stained blue with woad, though!

In the villas, hypocaust flooring used riven flagstone tiles or tegulae to form floors, and in the more important rooms the floors would be covered with mosaics, formed from thousands of tiny tesserae laid on a basic concrete known as opus signinum. Many of these mosaics were manufactured off-site, usually in southern Europe, prefabricated by highly skilled master mosaicists and selected from a catalogue by the client. They would be brought in to building projects when required and be laid by local tradesmen, much in the way that we do now with a feature patio.

Out of doors, function was far more important than form, and so courtyards were paved by using flagstone, setts and cobbles, with local materials dictating which style of paving was the most suitable. Where the local geology provided only poor or soft stone, beach or river cobbles, washed down from harder rock-beds miles upstream, could be used to provide a simple, hard-paved surface.

1,200 YEARS OF POTHOLES

The Roman control of Britain ended in the fifth century and with the loss of that control the last planned and methodical maintenance of the road network, so essential to ensuring military supremacy and the rule of law, also ended. The skills must have survived, but the political will was gone, and it would be a thousand years before any real political effort to maintain a serviceable road network would return.

The Dark Ages came and went, the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and others pushed their way in and paid scant attention to the finery and feats of their predecessors. They would use local materials to provide hard-standing for essential areas and fill in the odd pothole or two when it threatened to dislodge a wheel from their favourite cart, but paving, as a skilled trade, was relegated as the provision of food and shelter took precedence and the road network fell into decline.

Although they seem coarse and uncomfortable to modern taste, pitched stone roads were the best option for hundreds of years.

The Vikings also came and continued in much the same manner. Their towns would use stone paving in the busiest sections, but it was the responsibility of individual landowners to provide any hard surfacing that was required. Merchants and craftsmen might put down a few setts, cobbles or flagstones outside their place of business, perhaps to minimize the amount of mud and worse carried into their premises on the shoes and boots of customers, and there would be flagstones on the floors of the more upmarket properties, but most homes would rely on hard-packed, earthen floors with straw changed at irregular intervals.

Actual construction methods varied throughout the Roman Empire to make best use of local materials. This cross-section illustrates a typical construction for a British road which would be surfaced with gravels, rather than paved with flagstones or setts.

The Normans brought back the traditional skills of masonry, driven by their intensive programme of castle building, and the craft of the stone workers was employed for both vertical structures and for floors and courtyards. The basic tools used by Norman masons and paviors remain with us still. Hammers and wedges to split the stone, chisels and punches to dress it, and mallets to settle the stones into the bedding.

And so it went on. It was during the Tudor period, in 1555, that an Act of Parliament created the position of Surveyor of Highways, which was unpaid, unpopular and ineffective. Parishes were required to maintain their area’s roads and a bursary was issued to the local population who were required to ‘mend their ways’.

TURNPIKES, TAR AND TECHNICAL IMPROVEMENTS

It took until the late seventeenth century before properly maintained turnpike roads were established. The tolls imposed were used for their upkeep and extension, and the first successful road of this type was the Great North Road, now more commonly known as the A1. Other turnpike roads were developed throughout the later seventeenth century and their financial success led to their being expanded...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.9.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Garten | |

| Technik ► Bauwesen | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84797-327-2 / 1847973272 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84797-327-6 / 9781847973276 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich