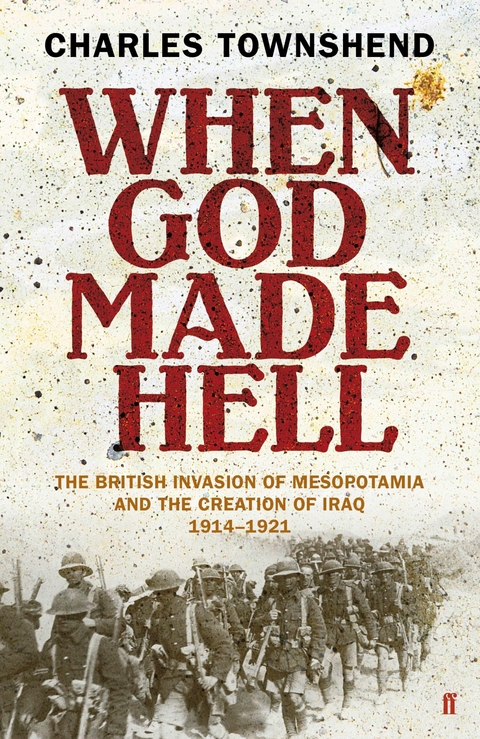

When God Made Hell (eBook)

624 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-26949-5 (ISBN)

Charles Townshend is Professor of International History at Keele University, specialising in the study of modern political violence and insurgency. He is the editor of the Oxford History of Modern War and the author of Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion, among others. He is married with two sons.

Since 2003, Iraq has rarely left the headlines. But less discussed is the fact that Iraq as we know it was created by the British, in one of the most dramatic interventions in recent history. A cautious strategic invasion by British forces led - within seven years - to imperial expansion on a dizzying scale, with fateful consequences for the Middle East and the world. In When God Made Hell, Charles Townshend charts Britain's path from one of its worst military disasters to extraordinary success with largely unintended consequences, through overconfidence, incompetence and dangerously vague policy. With monumental research and exceptionally vivid accounts of on-the-ground warfare, this a truly gripping account of the Mesopotamia campaign, and its place in the wider political and international context. For anyone seeking to understand the roots of British involvement in Iraq, it is essential reading.

Charles Townshend is Professor of International History at Keele University, specialising in the study of modern political violence and insurgency. He is the editor of the Oxford History of Modern War and the author of Easter 1916: the Irish Rebellion, among others. He is married with two sons.

Things are going on very bad here.

WILLIAM BIRD

On 16 October 1914, a British convoy sailed from Bombay, heading for Egypt. The Great War between the Western Allies and the Central Powers was nearly three months old, and troops of the Indian Army were making the long journey, via the Suez Canal, to join Britain’s battle against the German invasion of France. At this point, although Japan had attacked the German colony of Tsingtao (modern Qingdao), and small colonial armies were skirmishing in Africa, the war was still essentially a European clash. After the dramatic moves of August and September, it was heading towards stalemate. Russia’s invasion of Germany had been brought to a halt, as had Germany’s invasion of France. Austria-Hungary’s attempt to crush Serbia – the original cause of the war – had stalled. The Ottoman Empire, the bridge between Europe and Asia, was hovering on the brink of taking the German side. But for now it was still at peace with Britain, the power which for over a century had defended it against Russia’s ambition to seize the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, and the straits that linked the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

Once the convoy was out of Bombay, there was an unexpected development. Four of its ships contained the 16th Indian Brigade, belonging to the 6th (Poona) Division of the Indian Army, and ostensibly part of Indian Expeditionary Force A, on its way to the trenches in Flanders. As they steamed slowly across the Indian Ocean, the brigade commander, Brigadier-General Walter Delamain, opened sealed orders he had been handed on embarkation. His brigade was to divert into the Persian Gulf, becoming part of a new expeditionary force, whose mission was to protect British interests at the head of the Gulf. He was instructed that, if war broke out with Turkey, the rest of the division would join him as quickly as possible; until then he should avoid hostilities with the Turks and ‘friction with the Arabs’, but prepare not only to support Britain’s ally in Persia, the Sheikh of Mohammerah – who guaranteed the security of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s oilfields, pipeline, and refinery on Abadan Island – but also to occupy Basra: in other words to invade ‘Turkish Mesopotamia’.1 Britain’s global policy was on the brink of a dramatic shift.

On 23 October, under the protective guns of the battleship Ocean, Delamain’s force of 5,000 men arrived at Bahrain. This, he was informed by Sir Percy Cox, the British political representative in the Gulf, was ‘a quasi British protectorate’ (a deft way of describing a long and complicated relationship). It was also very hot. With no hint of a breeze, and drinking water soon running short, the troops were told they could not disembark. For day after day they, and still more their 1,200 animals – cavalry and artillery horses, and pack mules – sweltered in their iron hulls. ‘Things are going on very bad here,’ Private William Bird of the Dorset Regiment wrote in his pocket diary on the 26th, ‘the food is disgracefull – we are packed together like sardines.’ His brigadier reported that ‘our meat in hand will be finished on the 30th’; supplies of fuel on shore would last seven days. ‘No more cattle and no further wood procurable.’2

The brigade was trapped in its ships because Bahrain, although a ‘quasi protectorate’, where Britain had been patiently nurturing its influence for the last century, did not react well to the arrival of a British army. While the local people were used to British warships, which cruised the Persian Gulf in search of the pirates infesting the Arabian coast, troop transports were a different matter. Soon after they arrived, several deputations urged their sheikh to forbid the troops to land. The women seemed especially alarmed, and though the ladies of the American Mission did their best to calm them, as the days passed ‘the uneasiness of the people and their objection to the presence of the troops increased to a very considerable extent’. So much so that the British consul at Bahrain, Captain Keyes, also began to feel ‘some uneasiness’. The large Persian community there was strongly pro-German, and there was a general suspicion that Britain intended to occupy the islands permanently.3

Three days later, Private Bird, living on tinned pineapple and German mixed biscuits (confiscated from the warehouse of the Hamburg merchants Wonckhaus), was ‘beginning to wonder why we came this route’. After a week, some relief came in the form of boat drill to prepare for eventual landing – carefully avoiding the shore itself. For some it was comic relief: Pathans from the trans-frontier region and Sikh farmers were ‘not usually adepts at aquatic sports’, and many had never seen an oar. ‘The oars had a way of taking command’, and at least one man had a close encounter with a shark after being knocked out of his boat.4 But at last something happened. At the end of October shots were exchanged between Ottoman and Russian ships in the Black Sea – a staged ‘provocation’ signalling that Turkey intended to enter the war. Delamain’s force was ordered to move 300 miles northwards to the Shatt-al-Arab, at the head of the Gulf. Bird was elated: ‘Now understand everything,’ he wrote next day. ‘Just told war is declared on Turkey & we are going to Turkistan to fight them. All excitement & cheers galore.’ For him as for most soldiers, the dangers of combat were better than the boredom of idleness – especially on ships. (‘What’s the use of lectures?’ he had asked his diary: ‘Roll on the real thing.’)

Bird’s information was slightly premature. War was actually declared on 5 November, and Delamain put 500 men ashore at Fao, at the mouth of the Shatt-al-Arab, next day. A short bombardment by the 4-inch guns of their escorting sloop HMS Odin silenced the artillery in the old Turkish fort, and its defenders hastily abandoned it – luckily, since the carefully rehearsed landing operations did not work out well. The tide turned just as the landing began, ‘the boats swung around at anchor, the men lost what little skill they had’. Some boats landed, some were carried out to sea, some driven on to the Persian shore. The rest of the brigade reached Abadan next day, and on the 8th it finally disembarked on enemy soil. Now Bird not only shared the Dorsets’ eagerly anticipated ‘baptism of fire’, but he also had a glimpse of a different side of war. When a captured enemy scout refused to give any information, the interrogating officer ‘called up three men & made pretend that they would shoot him’. Bird seems to have found this an eminently sensible proceeding: ‘he soon came round.’5

Bird was not, in fact, in Turkistan, as he quickly discovered: he was in Mesopotamia. This Greek name, the land ‘between two rivers’ – Tigris and Euphrates – resonated deeply with all literate Europeans. And the Greek framed their take on it. It was the land of ancient history, the cradle of civilisation, the site of Ur and Babylon, the place where Alexander the Great died. Later religious myth located in it the Garden of Eden, and Noah’s flood. In 1914 few Westerners would know the Arabic name for the area, al-Iraq (the iraq being the long ridge in the desert that separated it from Syria). Since the Mongol conquest it had become a byword for decay and ruin. In ancient times it had supported the densest population on earth, and some thought it should still be able to support thirty million people.6 But it was now seriously underpopulated, with barely two million inhabitants. (The exact number could only be guessed, since the Ottomans did not attempt a census outside their Anatolian heartland.) The majority were Arabs, but there were big communities of Kurds, Christians and Jews in the north – in Baghdad itself, one of the world’s biggest urban Jewish communities, these minorities out numbered Arabs. It had no political or even administrative unity; the Ottoman government had actually separated the three vilayets (provincial governorships) of Baghdad, Basra and Mosul in the mid-nineteenth century. Baghdad’s pre-eminence remained indisputable. But even this fabled city was remote to the Turks themselves, who had a proverb: ‘a rumour will come back even from Baghdad’. For Ottoman bureaucrats, a posting to Basra or Baghdad was a dreaded form of exile. Outside those cities, governmental power was constantly disputed by turbulent tribal groups.

Like the rest of ‘Turkish Arabia’, as the British called the Arab lands of the Ottoman Empire, Mesopotamia was lamented as a sad shadow of the land of plenty that had once been the Fertile Crescent, arching from the Levant to the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. Its legendary fertility, due to once-magnificent irrigation systems, had died when they were destroyed by the Mongol ruler Hulagu in the fourteenth century. Disorder, depopulation, and the ‘silting and scouring of the rivers once let loose’, made restoration of control ‘the remote, perhaps hopeless problem today still unsolved’, as Stephen Longrigg wrote in the 1920s. The land was now alternately a desert and a swamp, a vast flat plain lying below the level of the great rivers, and regularly inundated as the embankments that contained them were ruptured by the spring floods of meltwater from the northern mountains. Between the awesome mountains of Kurdistan in the north, and the Gulf coast in the south, the plain hardly varied a hundred feet in height. When...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.10.2010 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | East vs West • foreign policy • imperialism • Invasion • war |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-26949-4 / 0571269494 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-26949-5 / 9780571269495 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich