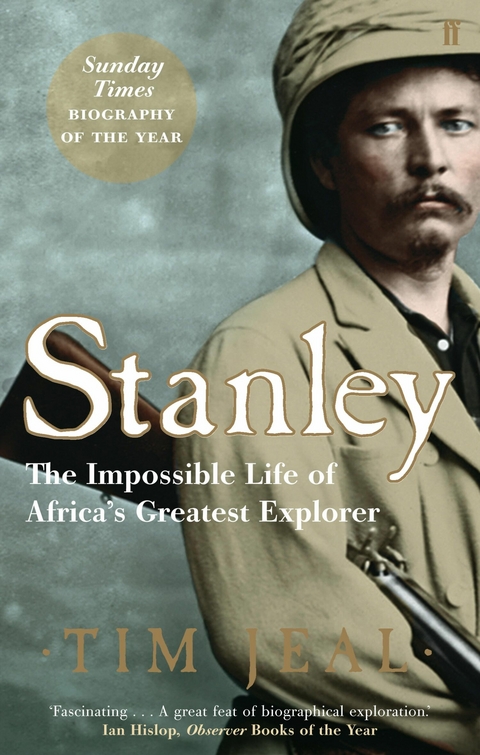

Stanley (eBook)

200 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-26564-0 (ISBN)

Tim Jeal is an acclaimed novelist and biographer, whose Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer was published by Faber in 2007 and was a BBC Radio Four 'Book of the Week'. Stanley was named Sunday Times Biography of the Year, and, in the US, won the National Book Critics' Circle Award in Biography for 2007. Tim's memoir Swimming with my Father was published by Faber in 2004 and was also a BBC Radio Four 'Book of the Week' and was shortlisted for the PEN Ackerley Prize for autobiography. In September 2011 Faber will publish Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure, which, thanks to much original research, will shed fascinating new light on the 'Search for the Nile' and its colonial consequences. In 1973 Tim Jeal's Livingstone (1973) was selected as a 'Notable Book of the Year' by the New York Times Book Review and one of the 'Best and Brightest of the Year' by the Washington Post Book World.Livingstone formed the basis for a BBC TV documentary and a film for the Discovery Channel. It has never been out of print. Nor has Tim Jeal's Baden-Powell (1989), which was a 'Notable Book of the Year', and was chosen by Channel 4 for its 'Secret Lives' strand. In 1975 Tim was awarded the John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize.

Henry Morton Stanley was a cruel imperialist - a bad man of Africa. Or so we think: but as Tim Jeal brilliantly shows, the reality of Stanley's life is yet more extraordinary. Few people know of his dazzling trans-Africa journey, a heart-breaking epic of human endurance which solved virtually every one of the continent's remaining geographical puzzles. With new documentary evidence, Jeal explores the very nature of exploration and reappraises a reputation, in a way that is both moving and truly majestic.

'Entirely gripping ... a rollicking read, as well as a moving, incisive study of one man's restless, evolving character and ambitions.'

'Superb ... Tim Jeal's absorbing biography will surely be definitive.'

Stanley has already been the subject of several major biographies. What does this one add? A great deal. [Jeal] brings to life the jarring paradoxes, the driving demons and the dreams of this extraordinary man... sympathetic yet balanced, perceptive and full of perspective, this is biography at its best.

When I contrast what I have achieved in my measurably brief life with what Stanley has achieved in his possibly briefer one, the effect is to sweep utterly away the ten-storey edifice of my own self-appreciation and to leave nothing behind but the cellar.

Mark Twain writing in 1886

In January 1963, when I was a few days short of my eighteenth birthday and waiting to go to university the following October, I set out overland from Cairo to Johannesburg on a zigzagging journey which I expected to last about four months. I made my way south, at first by Nile steamer and then in a succession of decrepit buses and trucks that juddered along roads at times resembling riverbeds, or sped along rust-coloured laterite tracks from which their tyres flung up clouds of choking dust. In small out-of-the-way places, a few care-worn travellers seemed always to be waiting anxiously at dusk, hoping to persuade our exhausted driver to take them on with him next day for whatever money they could afford to pay.

Such roadside staging posts would typically boast a single shop or duka, stocking cigarettes, matches, Coca-Cola and canned fish, with perhaps a bicycle repair shed nearby, and a single fuel pump, and someone selling steamed green bananas or cornmeal porridge under a tree. For a while those waiting would scan the road eagerly for a distant plume of dust, but would sink into a fatalistic reverie after a day or so. Until a vehicle appeared they could go no further, and with the nearest village perhaps a hundred or more miles away, there was absolutely nothing they could do about it.

Away from the ‘main’ road, a maze of faint single-file paths, which only locals knew, fanned into the bush. A guideless stranger would soon be lost and in real peril when his water ran out. In fact if anyone became separated from his fellows far from a village, he or she was likely to die in the bush, if not from thirst or exhaustion then in the jaws of a wild beast. In regions where the tsetse fly killed horses and oxen, riding and travelling by cart were impossible, leaving walking or cycling as the only remaining options. But who would try to walk hundreds of miles across uncharted country, when the rains could turn a road into a muddy morass within hours, and in high summer the heat could kill anyone without water and a shady place to rest? So the next truck, with its drums of extra fuel, spare tyres and life-saving food and water, offered the only chance.

Night comes rapidly in Africa, with twilight hardly existing, and the blackness seeming darker on account of its sudden arrival. For a while lamps and candles glow in huts and shacks, and adults talk and children play, but rarely till late in small wayside places. After that, on starless nights, the darkness is almost tangible, and when the crickets fall silent, the barking of a dog or the distant growl of some unidentified beast merely serves to emphasize the eerie silence that blankets the endless bush for miles around. At such moments, when I was not fretting over whether there was a snake or scorpion on the earth floor somewhere near my sleeping place, or whether my paludrine tablets, my insect-repelling creams and rarely used mosquito net would save me from malaria, I reminded myself that the Victorian explorers had possessed none of these things and yet had crossed the entire continent, not on known roads and tracks but through virgin bush and jungle, and along those dangerously illusive, vanishing paths that I would never consider using unless riding in a sturdy vehicle with someone who knew the area well.

During my trip, it first dawned on me why nineteenth-century explorers had needed a hundred or more African porters to accompany them into the interior. How else, lacking wheeled transport and draught animals because of the tsetse, could they have carried with them enough food and water, and sufficient beads, cloth and brass wire to buy fresh food supplies? And since their highly visible trade goods would have been a constant incitement to theft (a bit like carrying a bank around everywhere), I understood why expeditions had routinely been protected by armed Africans. As I passed slowly through recently independent Uganda, and soon to be independent Tanganyika, I was well aware that the great explorers were considered anachronistic embarrassments in this era when Africa’s future, rather than its colonial past, rightly claimed our attention. Even so, from that time onwards the realities of earlier exploration fascinated me, and in the early 1970s, a few years after I left Oxford, I wrote a life of David Livingstone that is still in print today.

Thirty-five years on, it is still hard for us to appreciate the immensely powerful hold that exploration exerted on the public imagination in nineteenth-century Europe and America. Then, the world had not yet been shrunk by the automobile and the aeroplane, and the planet’s remotest places seemed as inaccessible as the stars. From mid century, successful explorers were revered in much the same way as the Apollo astronauts would be just over a hundred years later. Very few achieved fame after 1871 – the year in which Stanley ‘found’ Livingstone – since by then, apart from apparently inaccessible central and sub-Saharan Africa, the only significant parts of the planet left unexplored were the equally daunting polar regions, along with northern Greenland and the north-east and north-west passages. But for the rapidly increasing populations of Europe’s and America’s factory towns, the romantic appeal of the world’s wilder outposts grew stronger. Stanley wrote in the 1870s that, in Africa, he felt freed from ‘that shallow life which thousands lead in England where a man is not permitted to be real and natural, but is held in the stocks of conventionalism’.

In an untamed land, a man was imagined to be free to cut down trees at will, kill game and navigate rivers, and to assume total responsibility for his own life. And that was what the explorers were imagined to be doing in Africa, with little account being taken of the appalling problems that overwhelmed most of them. In the novels of Fenimore Cooper, and those by Stanley’s friend Mark Twain – especially his two great novels of boyhood – the values of the frontier were exalted above those of the city. American adulation of frontiersmen like Boone and Crockett, and the heroes of the Wild West, was paralleled in Britain by a passion for African explorers, and a revival of interest in the Elizabethan seafarers. Then came Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines and She, and novels by Ballantine, Mayne Reid and Stevenson, which together completed the romantic (as opposed to the economic) underpinnings of the imperial impulse.

As an adventure-loving boy, Joseph Conrad had been entranced by ‘the blank spaces [on the map] then representing the unsolved mystery of that continent’. Yet romantic longings were so far removed from the realities of African travel that it is hard to imagine why so many men entertained them for so long. Really there was no mystery about why Conrad’s ‘blank spaces’ persisted, and why none of the great lakes had been ‘discovered’ by 1850, and why the continent’s two longest rivers, the Nile and the Congo, were still uncharted twenty years later. The awesome problems besetting Africa’s explorers began at the coast. Most rivers were harbourless and obstructed by surf-beaten sand bars, and blocked upstream by impassable rapids. In 1805 Mungo Park, a Scottish surgeon, and forty of the forty-four Europeans he had engaged to find the source of the river Niger, perished in the attempt. Park himself was murdered, while most of his men died of malaria. In 1816, the British naval officer James Tuckey was one of fourteen men to die on the Congo out of thirty who had volunteered to go on with him beyond the first cataracts. They travelled only 170 miles from the sea. Thirty-eight men died of fever out of forty-seven Britons on the Niger Expedition of 1833 to 1834, and Richard Lander, their leader, was murdered.

By crossing Africa between 1853 and 1856 and living to tell the tale, David Livingstone demonstrated that quinine aided resistance to malaria. But all Stanley’s white companions died during his search for Dr Livingstone, and the same thing happened during his trans-Africa journey. In fact, throughout the century, malaria remained a serious threat to life (as it still is), as did yellow fever and sleeping sickness. The health of survivors was often undermined, and very few saw old age. Lady Burton described her husband after an African journey as being ‘partially paralysed, partially blind … a mere skeleton, with brown yellow skin hanging in bags, his eyes protruding, his lips drawn away from his teeth’.1 And this degree of ill-health was not unusual.

Since the late Victorians were fixated by the need for manliness, the astonishing bravery of explorers earned them universal admiration. During my journey I had sometimes wondered how scared I would be if I ever found myself marooned in a truck that had broken down beyond repair in a rarely visited region. I imagined it would be like being shipwrecked on an inhospitable atoll and left to starve unless rescued. And this had been the fate of Victorian explorers deserted by their carriers, who had taken away with them...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.10.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Schlagworte | englishmen • exploration • Pioneers |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-26564-2 / 0571265642 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-26564-0 / 9780571265640 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich