Windvane Report (eBook)

228 Seiten

tredition (Verlag)

978-3-347-33082-5 (ISBN)

Born in 1947, Peter Förthmann is believed to have learned to sail about the same time as he learned to walk. Weary of school by the age of 16, he found a job with the Laeisz shipping company and completed the Pacific run on a banana boat seven times before concluding life in the merchant marine was never going to live up to his romantic childhood dreams. Returning to education, he finished school, trained as an exporter specialising in trade with Africa and then studied economics, moving into his twenties with a lust for life out of all proportion with his financial resources. Watercraft came and went at a rapid tempo; cars too in fact - mobility was the key - and by the time he reached 21, he had already acquired and disposed of more than a dozen boats. A pattern was soon established: restore, re-plank, strip down, repaint, fix the engine and then sail the boat as much and as far as possible until it catches someone's eye and sells itself, sometimes with astonishing rapidity. This was the gold rush era for a man who understood very quickly being his own boss was the only way to go. Now beginning to move up the food chain, Peter was sailing his own newly built yacht by the age of 25 and reached for the stars at 28 with a substantial steel yawl, which he ended up swapping for the Windpilot company in 1976. The rest is history - albeit a history focused almost exclusively on transom ornaments. Seemingly never short of ideas, Peter soon set about (the ongoing task of) completely rewriting the rules for windvane self-steering systems, also finding the time to exhibit at 220 international boat shows and put his acquired expertise down on paper in books that are now available in six languages. Peter Förthmann operates what may very well be Germany's smallest industrial manufacturing company together with this wife and sells directly to the sailing community worldwide. Building Windpilot into the global market leader has only stoked his passion for writing and his acerbic yet humorous, not to mention frequently self-deprecating, columns portray a man comfortable in his own skin who is still only just getting started ...

Born in 1947, Peter Förthmann is believed to have learned to sail about the same time as he learned to walk. Weary of school by the age of 16, he found a job with the Laeisz shipping company and completed the Pacific run on a banana boat seven times before concluding life in the merchant marine was never going to live up to his romantic childhood dreams. Returning to education, he finished school, trained as an exporter specialising in trade with Africa and then studied economics, moving into his twenties with a lust for life out of all proportion with his financial resources. Watercraft came and went at a rapid tempo; cars too in fact - mobility was the key - and by the time he reached 21, he had already acquired and disposed of more than a dozen boats. A pattern was soon established: restore, re-plank, strip down, repaint, fix the engine and then sail the boat as much and as far as possible until it catches someone's eye and sells itself, sometimes with astonishing rapidity. This was the gold rush era for a man who understood very quickly being his own boss was the only way to go. Now beginning to move up the food chain, Peter was sailing his own newly built yacht by the age of 25 and reached for the stars at 28 with a substantial steel yawl, which he ended up swapping for the Windpilot company in 1976. The rest is history - albeit a history focused almost exclusively on transom ornaments. Seemingly never short of ideas, Peter soon set about (the ongoing task of) completely rewriting the rules for windvane self-steering systems, also finding the time to exhibit at 220 international boat shows and put his acquired expertise down on paper in books that are now available in six languages. Peter Förthmann operates what may very well be Germany's smallest industrial manufacturing company together with this wife and sells directly to the sailing community worldwide. Building Windpilot into the global market leader has only stoked his passion for writing and his acerbic yet humorous, not to mention frequently self-deprecating, columns portray a man comfortable in his own skin who is still only just getting started ...

Hilfsrudersystem Hydrovane on Ovni 435

PREVAILING SYSTEM TYPES TODAY

Auxiliary rudder systems

An auxiliary rudder is an additional rudder capable of steering the boat independently with no connection to the main rudder. An auxiliary rudder needs to be about a third of the size of the boat’s main rudder to provide good results. Any smaller and it will struggle to steer effectively. The main rudder is fixed in position so that the boat is roughly balanced and the auxiliary rudder then handles the minor corrections required to keep the boat on course. The steering force these systems can apply is limited because they lack any sort of servo unit and they are therefore only able to provide effective self-steering for boats up to a certain size.

Auxiliary rudder systems ideally need to be mounted on centre. Offset mounting compromises steering performance because of the effect of heeling: rudder area that is in the air rather than the water serves no purpose whatsoever! The auxiliary rudder also needs to be sufficiently far back from the main rudder that it is not operating in the latter’s turbulent wash. An auxiliary rudder can be used as an emergency rudder, although having so much less surface area than the main rudder, it cannot be expected to provide more than limited steering if the entire main rudder is lost.

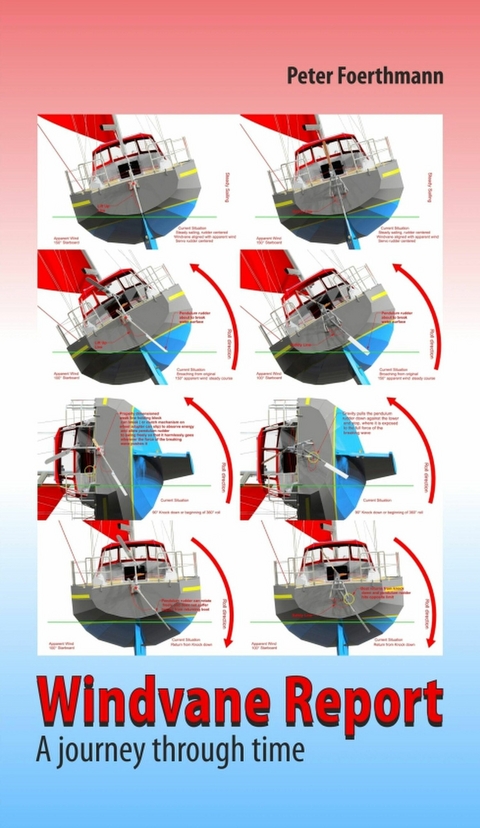

Servo-pendulum systems

A servo-pendulum system uses the power of the water flowing past the hull to generate servo forces that are transmitted to the main rudder via a system of lines. The force available depends on the length of the pendulum arm – the lever on which the water acts – from the bottom end of the rudder blade to the axle around which the pendulum arm pivots (servo force leverage), which is usually about 150-200 cm. Servo-pendulum systems can cope with boats of almost any size: bigger rudders just need a longer pendulum arm to generate the required force. They can only really be used with mechanical steering systems (wheel or tiller) though and do not perform so well with wheel steering systems that have more than 2.5 to 3 full rotations of the wheel from end stop to end stop. Connecting the self-steering up to the emergency tiller rather than the wheel can be an option, but only if the emergency tiller is robust. It is also important that the emergency tiller be within easy reach of the crew on watch, as it must be possible to disengage the windvane and resume steering by hand immediately in an emergency.

Servo-pendulum system on SV Thuriya at the start of the Golden Globe Race

The most convenient servo-pendulum systems for everyday use are those that allow the pendulum rudder to be swung up out of the water easily (lift-up). The system must be quick and straightforward to set up too if it is to be a practical option for short stints at the helm (when the chart table or nature calls, for example) as well as long. The handling disadvantages of traditional servo-pendulum systems are undoubtedly the main reason – along with their rustic looks – that they never became more popular. Although there have probably always been some owners who kept a windvane self-steering system just to cultivate a certain image despite an apparent immunity to the call of the cruel sea, for a long time it was virtually a sure thing that a boat with a mechanical windvane self-steering system on the transom had covered some serious bluewater miles (or was about to).

Manoeuvring in port under engine with a servo-pendulum system installed is only possible with the pendulum rudder raised. The pendulum rudder cannot be immobilised, so any attempt to reverse with it still in the water is certain to end with it swinging forcibly to one side or the other and crashing into any end stops that happen to be in the way. This is the sort of mistake a sailor makes only once.

Modern systems provide a lift-up capability that allows the pendulum arm (and pendulum rudder) to be swung up to one side into a parked position out of harm’s way. Traditional systems, in contrast, require the user to undo a catch or hinge before the rudder can be raised (sideways or aft) out of the water. A servo-pendulum gear will drive a tiller and a wheel equally well provided the boat’s steering system is mechanical rather than hydraulic.

The defining feature of all servo-pendulum systems is the enormous servo force they can bring to bear – sufficient, in fact, to keep a boat of 60 feet and 30 tonnes under control if the transmission lines have a clear run to the helm. All servo-pendulum systems are much more powerful than any auxiliary rudder system – and the right servo-pendulum system installed correctly can steer successfully even at every low speeds and in very light winds. There are Colin Archer replicas in Norway weighing 60 or 70 tonnes that manage fine with a tiller and have no problem using a servo-pendulum system for self-steering. Tensile forces of up to 200 kg are perfectly feasible in such a setting given the right pendulum rudder shaft length (for leverage) and sufficient boat speed. The actual force required to move the main rudder is hardly likely to come anywhere near this theoretical maximum because the crew will invariably shorten sail to reduce weather helm (for context, most human helms judge the amount of weather helm on the wheel or tiller to be excessive when the steering force required reaches more than about 5-8 kg). An experienced skipper knows that too much weather helm is slow and will have no hesitation in calling for a reef or sail change.

Line transfer of Windpilot Pacific on Maxi 33

The transmission lines that link the vane gear to the helm need to be laid out carefully, as virtually all servo-pendulum systems have a maximum travel in the region of 25 cm and therefore cannot afford to lose much efficiency to transmission errors.

Double rudder systems

Double rudder system Windpilot Pacific Plus on SV Adios Labor in Las Palmas

Combining the power of a servo-pendulum system with the independence (from the main rudder) of an auxiliary rudder unites the advantages of both systems and provides the best steering performance of all. The main rudder is fixed in position to balance the boat leaving the double rudder system to look after course corrections essentially untroubled by weather helm. Double rudder systems can deliver effective steering provided the auxiliary rudder blade is roughly a third of the size of the main rudder. Double rudder systems have to be mounted on centre because the servo rudder needs to be in the water all the time. Mount it offset to one side and the pendulum rudder would be left high and dry when the boat heels the wrong way. Wash from the main rudder can compromise the performance of double rudder systems too so it is important to allow sufficient separation between the main rudder and the auxiliary rudder element.

A double rudder system can be used as an emergency rudder.

SV Jonathan a Koopmans 44 in Antartica

Types of Boat

Choosing a boat is often enough a question of faith for sailors. The choice can be heavily influenced by subjective reactions and feelings that frequently have little to do with practical considerations. Errors of judgement made at this stage often become apparent only much later or in particular circumstances such as especially heavy weather. In discussing the various boat types, particular attention is paid – not surprisingly I would suggest – to the features that influence their suitability for use with windvane self-steering.

Long-keelers

Yachts with a long keel hold a course well, are enormously seaworthy and have a strong structure with a robust backbone. The rudder sits at the trailing edge of the keel. The combination of a V-form forefoot and S–shaped frames further aft gives a smooth ride through waves, making this type of boat comfortable and quiet to sail. The daring feats of the unmotorised double-ended rescue cutters designed by legendary Norwegian Colin Archer, which saved countless fishermen in peril on the North Atlantic in the most hideous of conditions, have inspired a legion of fans around the world who continue to admire and enjoy the capabilities of this hull form. Archer’s work also inspired a huge number of other yacht designers and builders and the Archer formula remains synonymous with virtually unlimited seaworthiness. Sailors the world over know exactly what the CA mark means.

SV Lucipara a Buchanan 47

Bernard Moitessier was a fan of this type of design too. His Joshua, which looked set to win him the Golden Globe Race until he decided more sailing was preferable to fame and fortune and carried on to Tahiti instead of returning to Europe and his chance of victory, was a steel double-ender very much in the Archer tradition. Boats almost identical to Moitessiers are still being built under the Joshua name today.

Long-keelers are good at holding a straight course but once they begin to wander, the steering force required to bring them back to the correct heading is substantial because the main rudder is not balanced. This means that effective self-steering can only be achieved with a servo-assisted windvane system or a sufficiently powerful autopilot. Handling a long-keeler at close quarters and in port is not a task for the faint-hearted. Strong nerves, a cool head and/or plenty of big fenders are very much the order of the day!

Whether long-keelers are really safer and more seaworthy than fin-and-skeg designs is a debate that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.5.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Ahrensburg |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Hausbau / Einrichten / Renovieren |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Schlagworte | bluewater • boat • Practice • Sailing • selfsteering • windsteering |

| ISBN-10 | 3-347-33082-X / 334733082X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-347-33082-5 / 9783347330825 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich