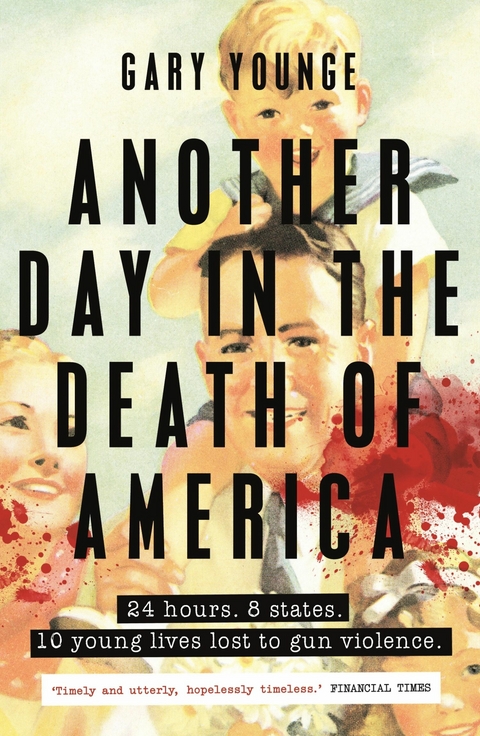

Another Day in the Death of America (eBook)

288 Seiten

Guardian Faber Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-78335-103-9 (ISBN)

Gary Younge is an award-winning author, broadcaster and professor of sociology at the University of Manchester. Formerly a columnist and an editor-at-large at the Guardian, he is an editorial board member of The Nation magazine. He is the author of five books, including Another Day in the Death of America (shortlisted for the Orwell Prize and the Jhalak Prize); his writing has appeared in Granta, the New York Times, the Financial Times, GQ, the New Statesman, and beyond, and he has made several radio and television documentaries on subjects ranging from gay marriage to Brexit. Younge received the 2023 Orwell Prize for Journalism. In 2025 he received the prestigious Robert B. Silvers Award in recognition of his exceptional contribution to the field of journalism. He lives in London. @garyyounge www.garyyounge.com

BY THE WINNER OF THE ORWELL PRIZE FOR JOURNALISM 2023SHORTLISTED FOR THE ORWELL PRIZE, THE JHALAK PRIZE, THE CWA GOLD DAGGER FOR NON-FICTION AND THE BREAD AND ROSES AWARDSaturday, 23rd November 2013. It was just another day in America. And as befits an unremarkable day, ten children and teens were killed by gunfire. Far from being considered newsworthy, these everyday fatalities are simply a banal fact. The youngest was nine; the oldest nineteen. None made the news. There was no outrage at their passing. It was simply a day like any other day. Gary Younge picked it at random, searched for the families of these children and here, tells their stories. Another Day in the Death of America explores the way these children lived and lost their short lives, offering a searing portrait of the vulnerability of youth in contemporary America.

This is Gary Younge's masterwork. You will never read news reports about gun violence the same way again. Brilliantly reported, quietly indignant and utterly gripping. A book to be read through tears.

This book is a righteous challenge to the big insanities of American society; gun ubiquity, racism, poverty and the supine and bland media which taboos genuine discourse on them. It's all the more daring and subversive for its controlled and mannered tone, as it breaks the unwritten law: thou shall not humanize the victims of this ongoing carnage.

The most common adjective employed by weather reporters on Saturday, 23 November 2013, was ‘treacherous’. But in reality there was not a hint of betrayal about it. The day was every bit as foul as one would expect the week before Thanksgiving. A ‘Nordic outbreak’ of snow, rain and high winds barrelled through the desert states and northern plains towards the Midwest. Wet roads and fierce gusts in northeast Texas forced Willie Nelson’s tour bus into a bridge pillar not far from Sulphur Springs in the early hours, injuring three band members and resulting in the tour’s suspension. With warnings of a 500-mile tornado corridor stretching north and east from Mississippi, the weather alone killed more than a dozen people.1 And as the low front shifted eastwards, so did the threat to the busiest travel period of the year, bringing chaos so predictable and familiar that it has provided the plot line for many a seasonal movie.

There was precious little in the news to distract anyone from these inclement conditions. A poll that day showed President Barack Obama suffering his lowest approval ratings for several years. That night he announced a tentative deal with Iran over its nuclear programme. Republican Senate minority whip John Cornyn believed that the agreement, hammered out with six allies as well as Iran, was part of a broader conspiracy to divert the public gaze from the hapless roll-out of the new health care website. ‘Amazing what WH [White House] will do to distract attention from O-care,’ he tweeted.2 Not surprisingly, another of the day’s polls revealed that two-thirds of Americans thought the country was heading in the wrong direction. That night, Fox News was the most popular cable news channel; The Hunger Games: Catching Fire was the highest-grossing movie, and the college football game between Baylor and Oklahoma State was the most-watched programme on television.

It was just another day in America. And as befits an unremarkable Saturday in America, ten children and teens were killed by gunfire. Like the weather that day, none of them would make big news beyond their immediate locale because, like the weather, their deaths did not intrude on the accepted order of things but conformed to it. So in terms of what one might expect of a Saturday in America, there wasn’t a hint of ‘betrayal’ about this either; it’s precisely the tally the nation has come to expect. Every day, on average, 7 children and teens are killed by guns; in 2013 it was 6.75 to be precise.3 Firearms are the leading cause of death among black children under the age of nineteen and the second-leading cause of death for all children of the same age group, after car accidents.4 Each individual death is experienced as a family tragedy that ripples through a community but the sum total barely earns a national shrug.

Those shot on any given day in different places and very different circumstances lack the critical mass and tragic drama to draw the attention of the nation’s media in the way a mass shooting in a cinema or church might. Far from being considered newsworthy, these everyday fatalities are simply a banal fact of death. They are white noise set sufficiently low to allow the country to go about its business undisturbed: a confluence of culture, politics and economics that guarantees that each morning several children will wake up but not go to bed while the rest of the country sleeps soundly.

It is that certainty on which this book is premised. The proposition is straightforward. To pick a day, find the cases of as many young people who were shot dead that day as I could, and report on them. I chose a Saturday because although the daily average is 6.75 that figure is spread unevenly. It is over the weekend, when school is out and parties are on, that the young are most likely to be shot. But the date itself – 23 November – was otherwise arbitrary. That’s the point. It could have been any day. (Were I searching for the highest number of fatalities, I would have chosen a day in the summer, for children are most likely to be shot when the sun is shining and they are in the street.)

There were other days earlier or later that week when at least seven children and teens were shot dead. But they were not the days I happened to choose. This is not a selection of the most compelling cases possible; it is a narration of the deaths that happened. Pick a different day, you get a different book. Fate chose the victims; time shapes the narrative.

And so on this day, like most others, they fell – across America, in all its diverse glory. In slums and suburbs, north, south, west and Midwest, in rural hamlets and huge cities, black, Latino, and white, by accident and on purpose, at a sleepover, after an altercation, by bullets that met their target and others that went astray. The youngest was nine, the oldest nineteen.

For eighteen months I tried to track down anyone who knew them – parents, friends, teachers, coaches, siblings, caregivers – and combed their Facebook pages and Twitter feeds. Where official documents were available regarding their deaths – incident reports, autopsies, 911 calls – I used them too. But the intention was less to litigate the precise circumstances of their deaths than to explore the way they lived their short lives, the environments they inhabited and what the context of their passing might tell us about society at large.

The New York Times quotation for that day came from California Democratic congressman Adam B. Schiff, who found twenty minutes to meet with Faisal bin Ali Jaber. Jaber’s brother-in-law and nephew were incinerated by a US drone strike in rural Yemen while trying to persuade Al Qaeda members to abandon terrorism. Schiff said after the meeting, ‘It really puts a human face on the term “collateral damage”.’5 My aim here is to put a human face – a child’s face – on the ‘collateral damage’ of gun violence in America.

*

I am not from America. I was born and raised in Britain by Barbadian immigrants. I came to the United States to live in 2003, shortly before the Iraq War, with my American wife, as a correspondent for the Guardian. I started out in New York, moved to Chicago after eight years, and left for Britain during the summer of 2015, shortly after finishing this book.

As a foreigner, reporting from this vast and stunning country over more than a decade felt like anthropology. I saw it as my mission less to judge the United States – though as a columnist I did plenty of that, too – than to try to understand it. The search for answers was illuminating, even when I never found them or didn’t like them. For most of that time, the cultural distance I enjoyed as a Briton felt like a blended veneer of invincibility and invisibility. I thought of myself less as participant than onlooker.

But, somewhere along the way, I became invested. That was partly about time. As I came to know people, rather than just interviewing them, I came to relate to the issues more intimately. When someone close to you struggles with chronic pain and has no health care or cannot attend a parent’s funeral because she is undocumented, your relationship to issues such as health reform and immigration is transformed. Not because your views change, but because knowing and understanding something simply does not provide the same intensity as having it in your life.

But my investment was also primarily about my personal circumstances. On the weekend in 2007 that Barack Obama declared his presidential candidacy, our son was born. Six years later, we had a daughter. I kept my English accent. But my language relating to children is reflexively American: ‘diapers’ instead of ‘nappies’, ‘stroller’ instead of ‘push chair’, ‘pacifier’ instead of ‘dummy’. I have only ever been a parent in the United States – a role for which my own upbringing in England provided no real reference point. For one of the things I struggled most to understand – indeed, one of the aspects of American culture most foreigners find hardest to understand – was the nation’s gun culture.

In this regard, America really is exceptional. American teens are seventeen times more likely to die from gun violence than their peers in other high-income countries. In the United Kingdom, it would take more than two months for a proportionate number of child gun deaths to occur.6 And by the time I’d come to write this book, I’d been in the country long enough to know that things were exponentially worse for black children like my own.

It ceased to be a matter of statistics. It was in my life. One summer evening, a couple of years after we moved to Chicago, our daughter was struggling to settle down, and so my wife decided to take a short walk to the local supermarket to bob her to sleep in the carrier. On her way back, there was shooting in the street, and she sought shelter in a local barbershop. In the year we left, once the snow finally melted, a discarded gun was found in the alley behind our local park and another in the alley behind my son’s school. My days of being an onlooker were over. Previously, I’d have found these things interesting and troubling. Now it was personal. I had skin in the game. Black skin in a game where the odds are stacked against it.

Around the time of my departure, those odds...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.9.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Politik / Gesellschaft | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | banning guns • Gun Control • gun laws • highschool shooting • mass shootings • NRA • US gun laws |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78335-103-9 / 1783351039 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78335-103-9 / 9781783351039 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich