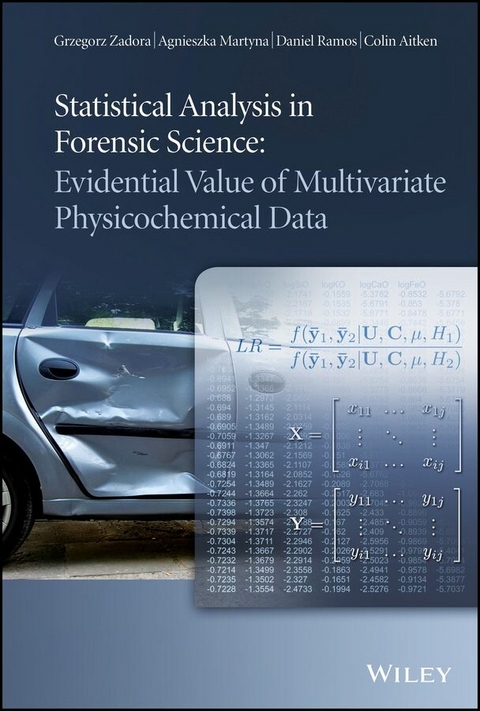

Statistical Analysis in Forensic Science (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-76318-6 (ISBN)

A practical guide for determining the evidential value of physicochemical data

Microtraces of various materials (e.g. glass, paint, fibres, and petroleum products) are routinely subjected to physicochemical examination by forensic experts, whose role is to evaluate such physicochemical data in the context of the prosecution and defence propositions. Such examinations return various kinds of information, including quantitative data. From the forensic point of view, the most suitable way to evaluate evidence is the likelihood ratio. This book provides a collection of recent approaches to the determination of likelihood ratios and describes suitable software, with documentation and examples of their use in practice. The statistical computing and graphics software environment R, pre-computed Bayesian networks using Hugin Researcher and a new package, calcuLatoR, for the computation of likelihood ratios are all explored.

Statistical Analysis in Forensic Science will provide an invaluable practical guide for forensic experts and practitioners, forensic statisticians, analytical chemists, and chemometricians.

Key features include:

- Description of the physicochemical analysis of forensic trace evidence.

- Detailed description of likelihood ratio models for determining the evidential value of multivariate physicochemical data.

- Detailed description of methods, such as empirical cross-entropy plots, for assessing the performance of likelihood ratio-based methods for evidence evaluation.

- Routines written using the open-source R software, as well as Hugin Researcher and calcuLatoR.

- Practical examples and recommendations for the use of all these methods in practice.

A practical guide for determining the evidential value of physicochemical data Microtraces of various materials (e.g. glass, paint, fibres, and petroleum products) are routinely subjected to physicochemical examination by forensic experts, whose role is to evaluate such physicochemical data in the context of the prosecution and defence propositions. Such examinations return various kinds of information, including quantitative data. From the forensic point of view, the most suitable way to evaluate evidence is the likelihood ratio. This book provides a collection of recent approaches to the determination of likelihood ratios and describes suitable software, with documentation and examples of their use in practice. The statistical computing and graphics software environment R, pre-computed Bayesian networks using Hugin Researcher and a new package, calcuLatoR, for the computation of likelihood ratios are all explored. Statistical Analysis in Forensic Science will provide an invaluable practical guide for forensic experts and practitioners, forensic statisticians, analytical chemists, and chemometricians. Key features include: Description of the physicochemical analysis of forensic trace evidence. Detailed description of likelihood ratio models for determining the evidential value of multivariate physicochemical data. Detailed description of methods, such as empirical cross-entropy plots, for assessing the performance of likelihood ratio-based methods for evidence evaluation. Routines written using the open-source R software, as well as Hugin Researcher and calcuLatoR. Practical examples and recommendations for the use of all these methods in practice.

Grzegorz Zadora, Institute of Forensic Research, Krakow, Poland. Daniel Ramos, Telecommunication Engineering, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Spain.

Preface xiii

1 Physicochemical data obtained in forensic science

laboratories 1

1.1 Introduction 1

1.2 Glass 2

1.3 Flammable liquids: ATD-GC/MS technique 8

1.4 Car paints: Py-GC/MS technique 10

1.5 Fibres and inks: MSP-DAD technique 13

References 15

2 Evaluation of evidence in the form of physicochemical data

19

2.1 Introduction 19

2.2 Comparison problem 21

2.3 Classification problem 27

2.4 Likelihood ratio and Bayes' theorem 31

References 32

3 Continuous data 35

3.1 Introduction 35

3.2 Data transformations 37

3.3 Descriptive statistics 39

3.4 Hypothesis testing 59

3.5 Analysis of variance 78

3.6 Cluster analysis 85

3.7 Dimensionality reduction 92

References 105

4 Likelihood ratio models for comparison problems 107

4.1 Introduction 107

4.2 Normal between-object distribution 108

4.3 Between-object distribution modelled by kernel density

estimation 110

4.4 Examples 112

4.5 R Software 140

References 149

5 Likelihood ratio models for classification problems

151

5.1 Introduction 151

5.2 Normal between-object distribution 152

5.3 Between-object distribution modelled by kernel density

estimation 155

5.4 Examples 157

5.5 R software 172

References 179

6 Performance of likelihood ratio methods 181

6.1 Introduction 181

6.2 Empirical measurement of the performance of likelihood

ratios 182

6.3 Histograms and Tippett plots 183

6.4 Measuring discriminating power 186

6.5 Accuracy equals discriminating power plus calibration:

Empirical cross-entropy plots 192

6.6 Comparison of the performance of different methods for LR

computation 200

6.7 Conclusions: What to measure, and how 214

6.8 Software 215

References 216

Appendix A Probability 218

A.1 Laws of probability 218

A.2 Bayes' theorem and the likelihood ratio 222

A.3 Probability distributions for discrete data 225

A.4 Probability distributions for continuous data 227

References 227

Appendix B Matrices: An introduction to matrix algebra

228

B.1 Multiplication by a constant 228

B.2 Adding matrices 229

B.3 Multiplying matrices 230

B.4 Matrix transposition 232

B.5 Determinant of a matrix 232

B.6 Matrix inversion 233

B.7 Matrix equations 235

B.8 Eigenvectors and eigenvalues 237

Reference 239

Appendix C Pool adjacent violators algorithm 240

References 243

Appendix D Introduction to R software 244

D.1 Becoming familiar with R 244

D.2 Basic mathematical operations in R 246

D.3 Data input 252

D.4 Functions in R 254

D.5 Dereferencing 255

D.6 Basic statistical functions 257

D.7 Graphics with R 258

D.8 Saving data 266

D.9 R codes used in Chapters 4 and 5 266

D.10 Evaluating the performance of LR models 289

Reference 293

Appendix E Bayesian network models 294

E.1 Introduction to Bayesian networks 294

E.2 Introduction to Hugin ResearcherTM software 296

References 308

Appendix F Introduction to calcuLatoR software 309

F.1 Introduction 309

F.2 Manual 309

Reference 314

Index 315

2

Evaluation of evidence in the form of physicochemical data

2.1 Introduction

The application of numerous analytical methods to the analysis of evidence samples returns various kinds of data (Chapter 1), which should be reliable. Confirmation that the data are reliable can be obtained when the particular analytical method is validated, that is, it is confirmed by the examination and provisions of objective evidence that the particular requirements for a specific intended use are fulfilled. Parameters such as repeatability, intermediate precision, reproducibility, and accuracy should be determined during the validation process for a particular quantitative technique. Therefore, statistical quantities such as standard deviations and relative standard deviations are usually calculated, and a regression/correlation analysis as well as an analysis of variance are usually carried out during the determination of the above-mentioned parameters (Chapter 3). This means that the use of statistical tools in the physicochemical analysis of evidence should not be viewed as a passing fad, but as a contemporary necessity for the validation process of analytical methods as well as for measuring the value of evidence in the form of physicochemical data.

It should also be pointed out that in general, representatives of the administration of justice, who are not specialists in chemistry, are not interested in details such as the composition of the analysed objects, except in a situation such as the concentration of alcohol in a driver’s blood sample or the content of illegal substances in a consignment of tablets or body fluids. Therefore, results of analyses should be presented in a form that can be understood by non-specialists, but at the same time the applied method of data evaluation should express the role of a forensic expert in the administration of justice. This role is to evaluate physicochemical data (evidence, E) in the context of the prosecution proposition H1 and defence proposition H2, that is, to estimate the conditional probabilities P(E|H1) and P(E|H2) (some basic information on probability can be found in Appendix A). H1 and H2 are raised by the police, prosecutors, and the courts and they concern:

The definition of the hypotheses H1 and H2 is an important part of the process in case assessment and interpretation methodologies considering likelihood ratios (Cook et al. 1998a; Evett 2011), as it conditions the entire subsequent evidence evaluation process. In particular, propositions can be defined at different levels in a so-called hierarchy of propositions (Aitken et al. 2012; Cook et al. 1998b). The first level in the hierarchy is the source level, where the inferences of identity are made considering the possible sources of the evidence. An example of propositions at the source level for a comparison problem is as follows:

- H1: the source of the glass fragments found in the jacket of the suspect is the window at the crime scene;

- H2: the source of the glass fragments found in the jacket of the suspect is some other window in the population of possible sources (windows).

Notice that at the source level the hypotheses make no reference to whether the suspect smashed the window or not, which should be addressed at the activity level. The hypotheses considered at this level are as follows:

- H1: the person (from whose clothes the glass fragments were recovered) broke a window at the crime scene;

- H2: the person (from whose clothes the glass fragments were recovered) did not break a window at the crime scene.

These hypotheses concern the problem of whether the person did something or not. A reliable answer to this question should also include the probabilities of incidental occurrence of glass fragments on the garments of the person due to, for example, contact with the person who actually did commit the crime or simple contamination.

The activity level makes no reference to whether the suspect committed the crime inside the house, which should be addressed at the offence level. The hypotheses considered at this level are as follows:

- H1: the person committed the crime,

- H2: the person did not commit the crime.

These are in fact the questions for the court involving some legal consequences. Thus, a forensic examiner typically starts to work with propositions at a source level. As more information is available in the case, it is possible to go up in the hierarchy of propositions and state propositions to the activity level. Nevertheless the offence level is reserved for the representatives of the court.

In this book, all the likelihood ratio computation methods consider the propositions defined at a source level, as these are the basic propositions in a case if no information other than the evidence is available.

2.2 Comparison problem

The evaluation of the evidential value of physicochemical data within the comparison problem requires taking into account the following aspects:

- possible sources of uncertainty (sources of error), which should at least include variations in the measurements of characteristics within the recovered and/or control items, and variations in the measurements of characteristics between various objects in the relevant population (e.g. the population of glass objects);

- information about the rarity of the determined physicochemical characteristics (e.g. elemental and/or chemical composition of compared samples) for recovered and/or control samples in the relevant population;

- the level of association (correlation) between different characteristics when more than one characteristic has been measured;

- in the case of the comparison problem, the similarity of the recovered material and the control sample.

Adopting a likelihood ratio (LR) approach allows the user to include all these factors in one calculation run. The LR is a well-documented measure of evidence value in the forensic field frequently applied in order to obtain the evidential value of various data (Chapter 1) being evaluated by a forensic expert (Aitken and Taroni 2004). Nevertheless, another so-called two-stage approach has been proposed. Both approaches are discussed in this section.

2.2.1 Two-stage approach

Within a two-stage approach (Aitken 2006a, b; Aitken and Taroni 2004; Lucy 2005) it is possible to compare two sets of evidence by using the data from these sets along with the application of suitable tests from the frequentist theory of hypothesis testing (Section 3.4). These are readily available in commercial statistical software. Nevertheless, the application of such an approach ignores information regarding the variability of the determined physicochemical values in a general population (rarity) and between-object variability. Therefore, this approach is a two-stage one, as it contains a comparison stage and then a rarity stage.

In the first stage, the recovered sample is compared with the control sample (e.g. physicochemical data obtained for a glass fragment recovered from a suspect’s clothing and a glass fragment collected from the scene of a crime) by application of Student’s t-test for univariate data or Hotelling’s T2-test for multivariate data (Section 3.4.7). The null hypothesis (H0) states that mean values of particular physicochemical features are equal for compared objects (e.g. means of univariate data such as glass refractive index values; Section 1.2.2) or vectors of mean values of multivariate data are equal (e.g. the elemental composition of an analysed object; Section 1.2.1) determined for control and recovered samples. H0 fails to be rejected when the calculated value of the significance probability (p) is larger than the assumed significance level (α; Section 3.4). Therefore, there is a binary outcome of this comparison as it could be decided that the control and recovered samples are similar or dissimilar.

If the objects are deemed dissimilar, then the analysis is stopped and it is decided to act as if the two pieces of evidence came from different sources. If the samples are deemed similar, the second stage is the assessment of the rarity of the evidence. This is an important part of the evaluation of evidence in the form of physicochemical data, as the above-mentioned significance tests take into account only information about within-object...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.12.2013 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Statistik |

| Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Wahrscheinlichkeit / Kombinatorik | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Analytical Chemistry • Analytische Chemie / Forensik • Angewandte Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung u. Statistik • Applied Probability & Statistics • Biowissenschaften • Chemie • Chemistry • Chemometrics • Daniel Ramos • evidence evaluation • Evidence evaluation methods • food authenticity analysis • Forensics • Forensic Science • forensic statistics • Forensik • Forensische Wissenschaft • Grzegorz Zadora • Life Sciences • likelihood ratio approach • multivariate physicochemical data • physicochemical data • Statistical Analysis in Forensic Science • statistical analysis of disease • statistical analysis of physicochemical data • statistical probability of disease • Statistics • Statistik • Statistische Analyse |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-76318-1 / 1118763181 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-76318-6 / 9781118763186 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich