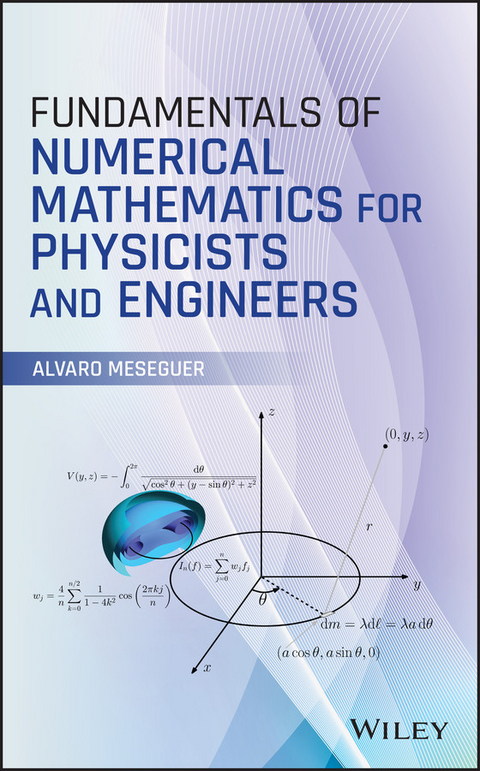

Fundamentals of Numerical Mathematics for Physicists and Engineers (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-42575-5 (ISBN)

Introduces the fundamentals of numerical mathematics and illustrates its applications to a wide variety of disciplines in physics and engineering

Applying numerical mathematics to solve scientific problems, this book helps readers understand the mathematical and algorithmic elements that lie beneath numerical and computational methodologies in order to determine the suitability of certain techniques for solving a given problem. It also contains examples related to problems arising in classical mechanics, thermodynamics, electricity, and quantum physics.

Fundamentals of Numerical Mathematics for Physicists and Engineers is presented in two parts. Part I addresses the root finding of univariate transcendental equations, polynomial interpolation, numerical differentiation, and numerical integration. Part II examines slightly more advanced topics such as introductory numerical linear algebra, parameter dependent systems of nonlinear equations, numerical Fourier analysis, and ordinary differential equations (initial value problems and univariate boundary value problems). Chapters cover: Newton's method, Lebesgue constants, conditioning, barycentric interpolatory formula, Clenshaw-Curtis quadrature, GMRES matrix-free Krylov linear solvers, homotopy (numerical continuation), differentiation matrices for boundary value problems, Runge-Kutta and linear multistep formulas for initial value problems. Each section concludes with Matlab hands-on computer practicals and problem and exercise sets. This book:

- Provides a modern perspective of numerical mathematics by introducing top-notch techniques currently used by numerical analysts

- Contains two parts, each of which has been designed as a one-semester course

- Includes computational practicals in Matlab (with solutions) at the end of each section for the instructor to monitor the student's progress through potential exams or short projects

- Contains problem and exercise sets (also with solutions) at the end of each section

Fundamentals of Numerical Mathematics for Physicists and Engineers is an excellent book for advanced undergraduate or graduate students in physics, mathematics, or engineering. It will also benefit students in other scientific fields in which numerical methods may be required such as chemistry or biology.

ALVARO MESEGUER, PHD, is Associate Professor at the Department of Physics at Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC BarcelonaTech), Barcelona, Spain, where he teaches Numerical Methods, Fluid Dynamics, and Mathematical Physics to advanced undergraduates in Engineering Physics and Mathematics. He has published more than 30 articles in peer-reviewed journals within the fields of computational fluid dynamics, and nonlinear physics.

ALVARO MESEGUER, PHD, is Associate Professor at the Department of Physics at Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC BarcelonaTech), Barcelona, Spain, where he teaches Numerical Methods, Fluid Dynamics, and Mathematical Physics to advanced undergraduates in Engineering Physics and Mathematics. He has published more than 30 articles in peer-reviewed journals within the fields of computational fluid dynamics, and nonlinear physics.

About the Author ix

Preface xi

Acknowledgments xv

Part I 1

1 Solution Methods for Scalar Nonlinear Equations 3

1.1 Nonlinear Equations in Physics 3

1.2 Approximate Roots: Tolerance 5

1.2.1 The Bisection Method 6

1.3 Newton's Method 10

1.4 Order of a Root-Finding Method 13

1.5 Chord and Secant Methods 16

1.6 Conditioning 18

1.7 Local and Global Convergence 20

Problems and Exercises 24

2 Polynomial Interpolation 29

2.1 Function Approximation 29

2.2 Polynomial Interpolation 30

2.3 Lagrange's Interpolation 33

2.3.1 Equispaced Grids 37

2.4 Barycentric Interpolation 39

2.5 Convergence of the Interpolation Method 43

2.5.1 Runge's Counterexample 46

2.6 Conditioning of an Interpolation 49

2.7 Chebyshev's Interpolation 54

Problems and Exercises 60

3 Numerical Differentiation 63

3.1 Introduction 63

3.2 Differentiation Matrices 66

3.3 Local Equispaced Differentiation 72

3.4 Accuracy of Finite Differences 75

3.5 Chebyshev Differentiation 80

Problems and Exercises 84

4 Numerical Integration 87

4.1 Introduction 87

4.2 Interpolatory Quadratures 88

4.2.1 Newton-Cotes Quadratures 92

4.2.2 Composite Quadrature Rules 95

4.3 Accuracy of Quadrature Formulas 98

4.4 Clenshaw-Curtis Quadrature 104

4.5 Integration of Periodic Functions 112

4.6 Improper Integrals 115

4.6.1 Improper Integrals of the First Kind 116

4.6.2 Improper Integrals of the Second Kind 119

Problems and Exercises 125

Part II 129

5 Numerical Linear Algebra 131

5.1 Introduction 131

5.2 Direct Linear Solvers 132

5.2.1 Diagonal and Triangular Systems 133

5.2.2 The Gaussian Elimination Method 135

5.3 LU Factorization of a Matrix 140

5.3.1 Solving Systems with LU 145

5.3.2 Accuracy of LU 147

5.4 LU with Partial Pivoting 150

5.5 The Least Squares Problem 160

5.5.1 QR Factorization 162

5.5.2 Linear Data Fitting 173

5.6 Matrix Norms and Conditioning 178

5.7 Gram-Schmidt Orthonormalization 183

5.7.1 Instability of CGS: Reorthogonalization 187

5.8 Matrix-Free Krylov Solvers 193

Problems and Exercises 204

6 Systems of Nonlinear Equations 209

6.1 Newton's Method for Nonlinear Systems 210

6.2 Nonlinear Systems with Parameters 220

6.3 Numerical Continuation (Homotopy) 224

Problems and Exercises 232

7 Numerical Fourier Analysis 235

7.1 The Discrete Fourier Transform 235

7.1.1 Time-Frequency Windows 243

7.1.2 Aliasing 246

7.2 Fourier Differentiation 251

Problems and Exercises 258

8 Ordinary Differential Equations 261

8.1 Boundary Value Problems 262

8.1.1 Bounded Domains 262

8.1.2 Periodic Domains 275

8.1.3 Unbounded Domains 277

8.2 The Initial Value Problem 279

8.2.1 Runge-Kutta One-Step Formulas 281

8.2.2 Linear Multistep Formulas 287

8.2.3 Convergence of Time-Steppers 297

8.2.4 A-Stability 301

8.2.5 A-Stability in Nonlinear Systems: Stiffness 315

Problems and Exercises 330

Solutions to Problems and Exercises 335

Glossary of Mathematical Symbols 367

Bibliography 369

Index 373

1

Solution Methods for Scalar Nonlinear Equations

1.1 Nonlinear Equations in Physics

Quite frequently, solving problems in physics or engineering implies finding the solution of complicated mathematical equations. Only occasionally, these equations can be solved analytically, i.e. using algebraic methods. Such is the case of the classical quadratic equation , whose exact zeros or roots are well known:

An obvious question is whether there is an expression similar to Eq. (1.1) providing the roots or zeros of the cubic equation . The answer is yes, and such expression is usually termed as Cardano's formula.1 We will not detail here the explicit expression of Cardano's formula but, as an example, if we apply such formulas to solve the equation

we can obtain one of its roots:

There are similar formulas to solve arbitrary quartic equations in terms of radicals, but not for quintic or higher degree polynomials, as proposed by the Italian mathematician Paolo Ruffini in 1799 but eventually proved by the Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel around 1824.

What we have described is just a symptom of a more general problem of mathematics: the impossibility of solving arbitrary equations analytically. This is a problem that has serious implications in the development of science and technology since physicists and engineers frequently need to solve complicated equations. In general, equations that cannot be solved by means of algebraic methods are called transcendental or nonlinear equations, i.e. equations involving combinations of rational, trigonometric, hyperbolic, or even special functions. An example of a nonlinear equation arising in the field of classical celestial mechanics is Kepler's equation2

where and are known constants. Another popular example can be found in quantum physics when solving Schrödinger's equation for a particle of mass in a square well potential of finite depth and width . In this problem, the admissible energy levels corresponding to the bounded states are the solutions of any of the two transcendental equations3:

where and is the reduced Planck constant. In this chapter, we will study different methods to obtain approximate solutions of algebraic and transcendental or nonlinear equations such as (1.2), (1.4), or (1.5). That is, while Cardano's formula (1.3) provides the exact value of one of the roots of (1.2), the methods we are going to study here will provide just a numerical approximation of that root. If you have a rigorous mathematical mind you may feel a bit disappointed since it seems always preferable to have an exact analytical expression rather than an approximation. However, we should first clarify the actual meaning of exact solution within the context of physics.

It is obvious that if the coefficients appearing in the quadratic equation are known to infinite precision, then the solutions appearing in (1.1) are exact. The same can be said for Cardano's solution (1.3) of cubic equation (1.2). However, equations arising in physics or engineering such as (1.4) or (1.5) frequently involve universal constants (such as Planck constant , the gravitational constant , or the elementary electric charge ). All universal constants are known with limited precision. For example, the currently accepted value of the Newtonian constant of gravitation is, according to NIST,4

As of 2019, the most accurately measured universal constant is

known as Rydberg constant. In other words, the most accurate physical constant is known with 12 digits of precision. Other equations may also contain empirical parameters (such as the thermal conductivity or the magnetic permeability of a certain material), which are also known with limited (and usually much less) precision. Therefore, the solutions obtained from equations arising in empirical sciences or technology (even if they have been obtained by analytical methods) are, intrinsically, inaccurate.

Current standard double precision floating point operations are nearly 10 000 times more accurate than the most precise universal constant known in nature. In this book, we will study how to take advantage of this precision in order to implement computational methods capable of satisfying the required accuracy constraints, even in the most demanding situations.

1.2 Approximate Roots: Tolerance

Suppose we want to locate the zeros or roots of a given function that is continuous within the interval . Mathematically, the main goal of exact root‐finding of in is as follows:

Root‐finding (Exact): Find such that .

However, computers work with finite precision and the condition cannot be exactly satisfied, in general. Therefore, we need to reformulate our problem:

Root‐finding (Approximate): For a given , find such that for some .

This reformulation introduces a new component in the problem: the positive constant , usually termed as tolerance, whose meaning is outlined in the plot on the right. Since the root condition cannot be satisfied exactly, we must provide an interval containing the root . In the figure on the right, the root lies within the interval .

1.2.1 The Bisection Method

In order to clarify the concept of tolerance we introduce here the bisection method (also called the interval halving method). Let us assume that is a continuous function within the interval within which the function has a single root . Since the function is continuous, . First, we define , , and as the starting interval whose midpoint is . The main goal of the bisection method consists in identifying that half of in which the change of sign of actually takes place. Use the simple rules:

Bisection Rules:

Finally set and .

Figure 1.1 (a) A simple exploration of reveals a change of sign within the interval (the root has been depicted with a gray bullet). (b) We start the bisection considering the initial interval . The bisection rule provides the new halved interval .

Figure 1.1 shows the result of applying the bisection rule to find roots of the cubic polynomial already studied in Eq. (1.2). As shown in Figure 1.1a, this polynomial takes values of opposite sign, and , at the endpoints of the interval whose midpoint is . Since , the new (halved) interval provided by the bisection rules is . The midpoint of (white triangle in Figure 1.1b) provides a new estimation of the root of the polynomial. We could resume the process by checking whether or in order to obtain the new interval containing the root and so on. After bisections we have determined the interval with midpoint . In general, the interval will be obtained by applying the same rules to the previous interval :

Bisection Method: Given such that , compute and set

This general rule that provides from is an example of what is generally termed as algorithm,5 i.e. a set of mathematical calculations that sometimes involves decision‐making. Since this algorithm must be repeated or iterated, the bisection method described above constitutes an example of what is also termed as an iterative algorithm.

Now we revisit the concept of tolerance seen from the point of view of the bisection process. For , the estimation of the root was , which is the midpoint of the interval , whereas for we obtain a narrower region of existence of such root, as well as its corresponding improved estimation . In other words, for the root lies within , with a tolerance , whereas for the interval containing the root is , with . Overall, after bisections, the tolerance is , becoming halved in the next iteration.

If we evaluate the radicals that appear in (1.3) with a scientific calculator, we can check that Cardano's analytical solution is approximately . Expression (1.3) is mathematically elegant, but not very practical if one needs an estimation of its numerical value. For we already have that estimation nearly within a or relative error. The reader may keep iterating further to provide better approximations of , overall obtaining the sequence . A natural question is whether this sequence has a limit. This leads to the mathematical concept of convergence of a sequence:

Convergence (Exact): The sequence is said to be convergent to if or, equivalently, if , where .

The difference appearing in the previous definition is called the error associated with . However, since may be positive or negative and we are just interested in the absolute discrepancy between and the root , it is common practice to define the absolute error of the th iterate. Checking convergence numerically using the previous definition has two main drawbacks. The first one is that we do not know the value of , which is precisely the goal of root‐finding. The second is that in practice we cannot perform an infinite number of iterations in order to compute the limit as , and therefore we must substitute...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.5.2020 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Algebra |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie | |

| Schlagworte | algorithms • Applied mathematics • applied physics • classical mechanics • Computational Physics • Computations • <p>Mathematics • Mathematical & Computational Physics • Mathematical Engineering • Mathematical Physics • Mathematics • Mathematik • Mathematische Physik • matrix computations • Nonlinear Equations • numerical</p> • Numerical Methods • numerische Methoden • Physics • Physik • Statistical Software / MATLAB • Statistics • Statistik • Statistiksoftware / MATLAB |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-42575-1 / 1119425751 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-42575-5 / 9781119425755 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich