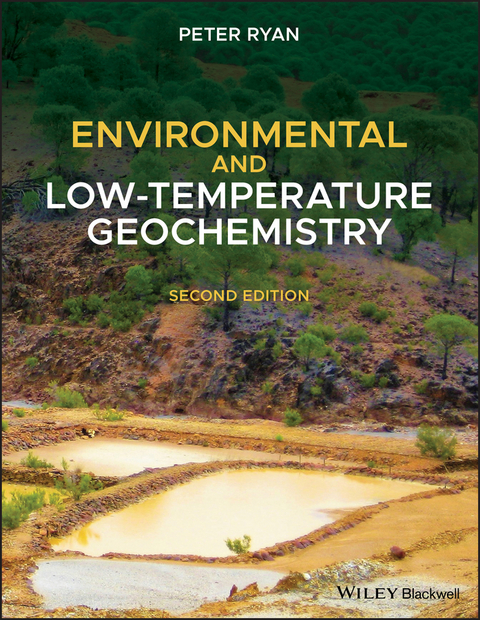

Environmental and Low-Temperature Geochemistry (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

9781119568612 (ISBN)

Environmental and Low-Temperature Geochemistry presents conceptual and quantitative principles of geochemistry in order to foster understanding of natural processes at and near the earth's surface, as well as anthropogenic impacts and remediation strategies. It provides the reader with principles that allow prediction of concentration, speciation, mobility and reactivity of elements and compounds in soils, waters, sediments and air, drawing attention to both thermodynamic and kinetic controls. The scope includes atmosphere, terrestrial waters, marine waters, soils, sediments and rocks in the shallow crust; the temporal scale is present to Precambrian, and the spatial scale is nanometers to local, regional and global.

This second edition of Environmental and Low-Temperature Geochemistry provides the most up-to-date status of the carbon cycle and global warming, including carbon sources, sinks, fluxes and consequences, as well as emerging evidence for (and effects of) ocean acidification. Understanding environmental problems like this requires knowledge based in fundamental principles of equilibrium, kinetics, basic laws of chemistry and physics, empirical evidence, examples from the geological record, and identification of system fluxes and reservoirs that allow us to conceptualize and understand. This edition aims to do that with clear explanations of fundamental principles of geochemistry as well as information and approaches that provide the student or researcher with knowledge to address pressing questions in environmental and geological sciences.

New content in this edition includes:

- Focus Boxes - one every two or three pages - providing case study examples (e.g. methyl isocyanate in Bhopal, origins and health effects of asbestiform minerals), concise explanations of fundamental concepts (e.g. balancing chemical equations, isotopic fractionation, using the Keq to predict reactivity), and useful information (e.g. units of concentration, titrating to determine alkalinity, measuring redox potential of natural waters);

- Sections on emerging contaminants for which knowledge is rapidly increasing (e.g. perfluorinated compounds, pharmaceuticals and other domestic and industrial chemicals);

- Greater attention to interrelationships of inorganic, organic and biotic phases and processes;

- Descriptions, theoretical frameworks and examples of emerging methodologies in geochemistry research, e.g. clumped C-O isotopes to assess seawater temperature over geological time, metal stable isotopes to assess source and transport processes, X-ray absorption spectroscopy to study oxidation state and valence configuration of atoms and molecules;

- Additional end-of-chapter problems, including more quantitatively based questions.

- Two detailed case studies that examine fate and transport of organic contaminants (VOCs, PFCs), with data and interpretations presented separately. These examples consider the chemical and mineralogical composition of rocks, soils and waters in the affected system; microbial influence on the decomposition of organic compounds; the effect of reduction-oxidation on transport of Fe, As and Mn; stable isotopes and synthetic compounds as tracers of flow; geological factors that influence flow; and implications for remediation.

The interdisciplinary approach and range of topics - including environmental contamination of air, water and soil as well as the processes that affect both natural and anthropogenic systems - make it well-suited for environmental geochemistry courses at universities as well as liberal arts colleges.

PETER RYAN is Professor of Geology and Environmental Studies at Middlebury College where he teaches courses in environmental geochemistry, hydrology, sedimentary geology and interdisciplinary environmental studies. He received a Ph.D. in geology at Dartmouth College, an M.S. in geology from the University of Montana and a B.A. in earth sciences from Dartmouth College. He has served as Director of the Program in Environmental Studies and as Chair of the Department of Geology at Middlebury College. His research interests fall into two main areas: (1) understanding the geological and mineralogical controls on trace element speciation, particularly the occurrence and mobility of arsenic and uranium in bedrock aquifers; and (2) the temporal evolution of soils in the tropics, with emphasis on mechanisms and rates of mineralogical reactions, nutrient cycling and application of soil geochemical analysis to correlation and geological interpretation.

PETER RYAN is Professor of Geology and Environmental Studies at Middlebury College where he teaches courses in environmental geochemistry, hydrology, sedimentary geology and interdisciplinary environmental studies. He received a Ph.D. in geology at Dartmouth College, an M.S. in geology from the University of Montana and a B.A. in earth sciences from Dartmouth College. He has served as Director of the Program in Environmental Studies and as Chair of the Department of Geology at Middlebury College. His research interests fall into two main areas: (1) understanding the geological and mineralogical controls on trace element speciation, particularly the occurrence and mobility of arsenic and uranium in bedrock aquifers; and (2) the temporal evolution of soils in the tropics, with emphasis on mechanisms and rates of mineralogical reactions, nutrient cycling and application of soil geochemical analysis to correlation and geological interpretation.

1

Background and Basic Chemical Principles: Elements, Ions, Bonding, Reactions

1.1 An Overview Of Environmental Geochemistry – History, Scope, Questions, Approaches, Challenges for the Future

The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas. (Linus Pauling)

All my life through, the new sights of nature made me rejoice like a child. (Marie Curie)

I must speak of the soil hiding the rocks, of the lasting river destroyed by time. (Pablo Neruda)

Environmental and low‐temperature geochemistry encompasses research at the intersection of geology, environmental studies, chemistry, and biology, and at its most basic level is designed to answer questions about the behavior of natural and anthropogenic substances at or near the surface of earth. The scope includes topics as diverse as trace metal pollution, soil formation, acid rain, sequestration of atmospheric carbon, and pathways of human–plant–wildlife exposure to contaminants. Most problems in environmental geochemistry require understanding of the relationships among aqueous solutions, geological processes, minerals, organic compounds, gases, thermodynamics and kinetics, and microbial influences, to name a few.

A good example to lay out some of the basic considerations in environmental and low‐temperature geochemistry is the fate and transport of lead (Pb) in the environment. In many regions of the Earth, Pb in the earth surface environment is (was) derived from combustion of leaded gasoline, because even in places where it has been banned (most of the world), Pb tends to persist in soil. The original distribution of Pb was controlled at least in part by atmospheric processes ranging from advection (i.e. wind) to condensation and precipitation.

Focus Box 1.1

Defining “Low‐Temperature”

In the world of geochemistry and mineralogy, “low‐temperature” environments generally refer to those at or near the Earth's surface, whereas “high‐temperature” environments include those deeper in the crust, i.e. igneous and metamorphic systems. Most geochemists consider tropical soils with mean annual temperature of 25 °C, alpine or polar systems with mean annual temperature of <5 °C, and sediments buried 1 km below the surface with a temperature of 50 °C, all as low‐temperature systems.

Once deposited on Earth's surface, the fate and transport of Pb is controlled by interactions and relationships among lead atoms, solids compounds (e.g. inorganic minerals or organic matter), plants or other organisms, and the composition of water in soils, lakes, or streams (including dissolved ions like Cl− and CO3 2− and gases like O2 and CO2). In cases where Pb falls on soils bearing the carbonate anion (CO3 2−), the formation of lead carbonate (PbCO3) can result in sequestration of lead in a solid state where it is largely unavailable for uptake by organisms. If the PbCO3 is thermodynamically stable, the lead can remain sequestered (i.e. in a solid state and relatively inert), but changes in chemical regime can destabilize carbonates. For example, acidic precipitation that lowers the pH of soil can cause dissolution of PbCO3, but how much of the carbonate will dissolve? How rapidly? Much like the melting of snow on a spring day, geochemical processes are kinetically controlled (some more than others), so even in cases where phases exist out of equilibrium with their surroundings, we must know something about rate laws in order to predict how fast reactions (e.g. dissolution of PbCO3) will occur.

Focus Box 1.2

Lead (Pb) and Environmental Justice

Humans have known for thousands of years that lead is toxic, dating back at least to the Roman Empire, but it remains problematic because it relatively abundant and easy to work (e.g. to make pipes for water systems, or as an additive to paint or fuel). A recent case that highlights the connection of geochemistry and human health is that of Flint, Michigan (USA), where lead‐bearing pipes were installed as part of the public water supply system in the early twentieth century. Beginning in 2014, a change in public water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River – and in part, the higher amounts of chloride anion (Cl−) in Flint River water – began to leach lead from the old lead‐bearing water mains (pipes) and fittings (Hanna‐Attisha et al. 2016). Evidence for the corrosion was obvious to residents in the form of brownish particulates that clouded their water and made it taste bad, but slow response from government resulted in exposure via ingestion. Lead is one of those elements that is harmful at any level, especially to the cognitive development of children. The crisis in Flint serves as one of many examples of environmental injustice (see “environmental (in)justice” in the index for more examples).

If Pb is dissolved into an aqueous form (e.g. Pb2+), additional questions of fate and transport must be addressed – will it remain in solution, thus facilitating uptake by plants? Or will it be carried in solution into a nearby surface water body, where it could be consumed by a fish or amphibian? Or will other soil solids play a role in its fate? Will it become adsorbed to the surface of a silicate clay or organic matter, transported downstream until it ultimately desorbs in lake sediments? We also need to consider the possibility that the PbCO3 does not dissolve, but rather is physically eroded as a particulate (grain) into a stream or lake, where it might dissolve or remain a solid, possibly becoming consumed by a bottom feeder, from which point it could biomagnify up the food chain.

Environmental geochemistry has its origins in groundbreaking advances in chemistry and geology ushered in by the scientific breakthroughs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly advances in instrumental analysis. The Norwegian Victor M. Goldschmidt is considered by many to be the founder of geochemistry, a reputation earned by his pioneering studies of mineral structures and compositions by X‐ray diffraction and optical spectrograph studies. These studies led Goldschmidt to recognize the importance and prevalence of isomorphous substitution in crystals, a process where ions of similar radii and charges can substitute for each other in crystal lattices.

Goldschmidt's peer, the Russian Vladimir I. Vernadsky, had come to realize that minerals form as the result of chemical reactions, and furthermore that reactions at the Earth's surface are strongly mediated by biological processes. The orientation of geochemistry applied to environmental analysis mainly arose in the 1960s and 1970s with growing concern about contamination of water, air, and soil. The early 1960s saw publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, and early research on acid rain at Hubbard Brook in New England (F.H. Bormann, G.E. Likens, N.M. Johnson, and R.S. Pierce) emphasized the interdisciplinary thinking required for problems that spanned atmospheric, hydrologic, soil, biotic, and geologic realms.

Current research in environmental geochemistry encompasses problems ranging from nanometer and micron scale (e.g. interactions between minerals and bacteria or X‐ray absorption analysis of trace metal speciation), local scale (e.g. acid mine drainage, leaking fuel tanks, groundwater composition, behavior of minerals in nuclear waste repositories) to regional (acid rain, mercury deposition, dating of glacier retreat and advance) and global (climate change, ocean chemistry, ozone depletion) scale. Modern environmental geochemistry employs analytical approaches ranging from field mapping and spatial analysis to spectrometry and diffraction, geochemistry of radioactive and stable isotopes, and analysis of organic compounds and toxic trace metals. While the explosion of activity in this field makes it impossible to present all developments and to acknowledge the research of all investigators, numerous published articles are cited and highlighted throughout the text, and two case studies that integrate many concepts are presented in Appendices I and II.

1.2 The Naturally Occurring Elements – Origins and Abundances

The chemical elements on Earth have been around for billions of years, thanks to nucleosynthesis, the Big Bang, approximately 12–15 billion years ago (especially the lighter elements), and processes in the interiors of stars later in the evolution of the universe (heavier elements). The early universe was extremely hot (billions of degrees) and for the first few seconds was comprised only of matter in its most basic form, quarks.

1.2.1 Origin of the light elements H and He (and Li)

Approximately 15 seconds after the Big Bang, the atomic building blocks known as neutrons, protons, electrons, positrons, photons, and neutrinos began to form from quarks, and within minutes after the Big Bang, the first actual atoms formed. Protons combined with neutrons and electrons to form hydrogen ( ) and its isotope deuterium ( , or D), which rapidly began to form helium (He) through fusion, a process in which the nuclei of smaller atoms are joined to create larger, heavier atoms: 2H → He + energy, or to be more precise:

where γ is the symbol for gamma radiation emitted during nuclear fusion. (Note: basic principles of atomic...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.11.2019 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Chemie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Mineralogie / Paläontologie | |

| Schlagworte | Boden- u. Geochemie • bonding and geochemistry • Chemie • Chemistry • earth sciences • elements geochemistry • enthalpy and heat </p> • Environmental Geochemistry • Environmental Geoscience • Geochemie, Mineralogie • Geochemistry & Minerology • Geowissenschaften • Gibbs energies • history of geochemistry • <p>Guide to low temperature geochemistry • principles of environmental geochemistry • reactions and geochemistry • Soil & Geochemistry • Umweltgeowissenschaften |

| ISBN-13 | 9781119568612 / 9781119568612 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich