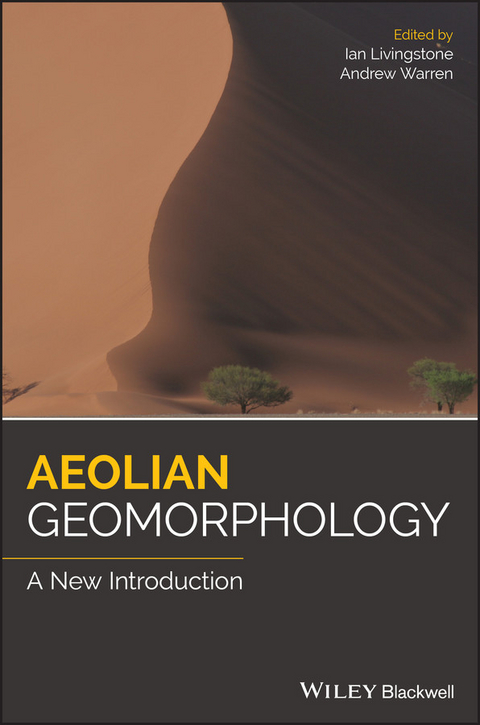

Aeolian Geomorphology (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-94563-6 (ISBN)

A revised introduction to aeolian geomorphology written by noted experts in the field

The new, revised and updated edition of Aeolian Geomorphology offers a concise and highly accessible introduction to the subject. The text covers the topics of deserts and coastlines, as well as periglacial and planetary landforms. The authors review the range of aeolian characteristics that include soil erosion and its consequences, continental scale dust storms, sand dunes and loess. Aeolian Geomorphology explores the importance of aeolian processes in the past, and the application of knowledge about aeolian geomorphology in environmental management.

The new edition includes contributions from eighteen experts from four continents. All the chapters demonstrate huge advances in observation, measurement and mathematical modelling. For example, the chapter on sand seas shows the impact of greatly enhanced and accessible remote sensing and the chapter on active dunes clearly demonstrates the impact of improvements in field techniques. Other examples reveal the power of greatly improved laboratory techniques. This important text:

- Offers a comprehensive review of aeolian geomorphology

- Contains contributions from an international panel of eighteen experts in the field

- Includes the results of the most recent research on the topic

- Filled with illustrative examples that demonstrate the advances in laboratory approaches

Written for students and professionals in the field, Aeolian Geomorphology provides a comprehensive introduction to the topic in twelve new chapters with contributions from noted experts in the field.

Ian Livingstone is Professor of Physical Geography and Head of the Graduate School, University of Northampton, UK.

Andrew Warren is an Emeritus Professor of Geography at University College London, UK.

A revised introduction to aeolian geomorphology written by noted experts in the field The new, revised and updated edition of Aeolian Geomorphology offers a concise and highly accessible introduction to the subject. The text covers the topics of deserts and coastlines, as well as periglacial and planetary landforms. The authors review the range of aeolian characteristics that include soil erosion and its consequences, continental scale dust storms, sand dunes and loess. Aeolian Geomorphology explores the importance of aeolian processes in the past, and the application of knowledge about aeolian geomorphology in environmental management. The new edition includes contributions from eighteen experts from four continents. All the chapters demonstrate huge advances in observation, measurement and mathematical modelling. For example, the chapter on sand seas shows the impact of greatly enhanced and accessible remote sensing and the chapter on active dunes clearly demonstrates the impact of improvements in field techniques. Other examples reveal the power of greatly improved laboratory techniques. This important text: Offers a comprehensive review of aeolian geomorphology Contains contributions from an international panel of eighteen experts in the field Includes the results of the most recent research on the topic Filled with illustrative examples that demonstrate the advances in laboratory approaches Written for students and professionals in the field, Aeolian Geomorphology provides a comprehensive introduction to the topic in twelve new chapters with contributions from noted experts in the field.

Ian Livingstone is Professor of Physical Geography and Head of the Graduate School, University of Northampton, UK. Andrew Warren is an Emeritus Professor of Geography at University College London, UK.

1

Global Frameworks for Aeolian Geomorphology

Andrew Warren

University College London, London, UK

1.1 Introduction

This chapter locates aeolian geomorphology in four global frameworks, arranged in increasing scale. The first is the framework of contemporary winds, from local to annual. The second is the changing erosivity of the wind and the erodibility of the surface during recent geological history. The third, digging deeper into the past, is the framework of the preparation and supply of sand and dust to the wind. The fourth, covered very briefly, is the yet wider and older framework of plate‐tectonics. Box 1.1 is a short early history of aeolian geomorphology.

Box 1.1 A Short Early History of Aeolian Geomorphology

It was not until the late nineteenth century, even the early twentieth century, that a significant number of geo‐scientists acknowledged that the wind was a major geomorphological agent. Rivers had been recognised in that role early in the century, particularly by Charles Lyell in his influential Principles of Geology (1875, first edition 1830). Lyell maintained that loess had been deposited by a flood, even the biblical Flood, not as dust, and ignored more obviously aeolian landforms. Despite pioneers like Udden (1894), Berg could still maintain that loess was a deep soil as late as 1916.

The principal catalyst to the aeolian enlightenment was the opening‐up of the world in the late nineteenth century, particularly its deserts. But experience, alone, was insufficient to come to a defensible interpretation. Keyes (1909), well acquainted as he was with the deserts of the western USA, could still assert that the wind could level mountains. More astute interpretation of direct observation, now of the Chinese loess, led both by von Richthofen (e.g. 1882), and the more influential ‘aeolianist’, Obruchev (e.g. 1895, Box Figure 1.1), to conclude that it was a deposit of aeolian dust. Obruchev’s observations on the deserts of central Asia, which he traversed on horseback, included wind‐eroded terrain, and the dust‐filled skies he experienced, strengthened his belief in the power of the wind. He went further to propose that loess‐sized particles could have been created either by glacial grinding, which is non‐aeolian (much debated; Chapter 4); or by the grinding of wind‐driven sand (a fully aeolian process), an idea which, although contested for decades, is enjoying rebirth (Crouvi et al. 2010). The location of some ‘desert loess’ (in southern Tunisia) is shown on Figure 1.12. The early study of loess is further discussed in Chapter 5.

Box Figure 1.1 Vladimir Afanasyevich Obruchev atop a mega‐yardang in his ‘Aeolian City’ near the Chinese/Russian border at somewhat NE of 46°N, 85°30″E (Obruchev’s coordinates; Obruchev 1911); and a portrait of the man himself.

First‐hand experience and critical interpretation also had a crucial role in shaping opinions about desert dunes. The pioneers here were a succession of French observers of the sand deserts of northern Africa, beginning with Rolland (e.g. 1890), who had been sent to reconnoitre the route of a trans‐Saharan railway through southern Algeria. Rolland argued that the dunes he saw, some large, were wholly the work of the wind, and had been aligned by the wind. He even speculated about the sources of the dune sand, and the distribution of sand seas, questions still asked. Rolland's ideas were developed by later French geomorphologists, particularly Aufrère (1930), whose work reached an international audience. There were still some blind alleys in the search for explanations of dunes, such as Vaughn‐Cornish’s wave theory (Goudie 2008), but in the 1930s two major revolutions in aeolian geomorphology were about to break.

In the early twentieth century, although it was generally accepted that the wind could erode, move, and deposit sediment, few asked how it did so. The gap in knowledge was dramatically narrowed by Bagnold (e.g. 1941), who, like Obruchev, had traversed many wind‐formed landscapes, in his case in south‐west Asia and north‐eastern Africa, and now travelling by motor car (Bagnold 1990). As an engineer, Bagnold focused mathematical modelling and experiments onto aeolian processes (Bagnold 1941; more in Chapter 2). He was probably the first to use a wind tunnel to study the movement of sand, and more certainly the first to study the mechanism of sand movement in the field (Box Figure 1.2). His wind tunnel was replicated by the Wind Erosion Research Unit in Kansas (see Chapter 12). In the Soviet Union, Znamenski (1958), who also replicated Bagnold’s design of wind tunnel, quoting him as “Bagnolg”. Bagnold's book is still the most commonly cited source in aeolian geomorphology. Development of many his ideas had to wait for decades (Chapter 2). One of his few excursions into application is described in Box 12.1 in Chapter 12. Bagnold is quoted in most of the chapters in this book.

Box Figure 1.2 Ralf Adger Bagnold measuring the wind‐speed profile and the flux of sand, near ‘Uweinat in southwestern Egypt in February 1938.

Source: Photograph: R.F. Peel.

The early twentieth century also saw a slower, more diffuse revolution, driven by the discovery of large areas of inactive aeolian terrain, as a by‐product of the growing realisation of the extent of Pleistocene climatic change in other fields of geomorphology. Pioneers in the study of these terrains and deposits included Cailleux (e.g. 1936) in respect of mainly northern Europe (but also some more exotic places); others worked on evidence from West Africa (summarised in Grove and Warren 1968), and yet others in North America, for example, Leighton (1931) on loess. At first, the dating of these ‘fossil’ landscapes had to rely on stratigraphy and palaeontology, a problem that was overcome, first, by radiocarbon dating (Libby 1952), and three decades later by luminescence dating, which is better suited to generally inorganic aeolian material, and has a much greater historical reach (Chapters 5 and 10). Other methods, like the use of cosmogenic isotopes, came still later and have even greater historical reach (Vermeesch et al. 2010).

Many more techniques have now made significant contributions to aeolian geomorphology: remote sensing, which has opened new vistas on dune form, and the local generation and the global movement of dust (Chapter 4), mathematical modelling of the movement of sediment and of the form of dunes (Chapter 6) and much more, as explained in the chapters that follow.

1.2 Wind

Chapter 2 of this book, ‘Grains in Motion’, covers the shortest, smallest and most fundamental of aeolian rhythms, leaving larger‐scale processes and their longer rhythms to be introduced in this chapter.

1.2.1 Wind Systems with Daily Rhythm and Local Scale

1.2.1.1 Dust Devils

The scientific term, dust devil, is a close translation of Dhūla kā śaitāna in the North Indian languages from which it was borrowed. Most dust devils blow in daytime, reach diameters of a few metres, last for a few minutes and travel a few hundreds of metres; a few are larger, longer‐lived and further‐travelled. Some dust devils leave shallow tracks, most do not (see also Chapters 4 and 11).

1.2.1.2 Haboobs

A haboob (, ‘blustery wind’ in Sudanese Arabic) is, in the contemporary climatological literature, a dusty, mobile thunderstorm that develops when and where warm, moist air is taken to otherwise hot, dry, sparsely vegetated, dust‐yielding environments, as in central Sudan and Arizona. A ‘cold pool’ develops at ground level within the thunderstorm and this pulls a strong downdraft. When the downdraft hits the ground, it bursts out horizontally at velocities of up to 20 ms−1. These gusts raise a large amount of dust from the surface, if it is available. The outer edge of the dust cloud is often a sharply‐defined, mobile ‘wall’ of dust. Most haboobs develop late in the day and last for less than a day. A haboob in Arizona on 5 July 2011 maintained a width of ~10 km, but elongated to ~80 km, as it moved slowly east‐south‐eastward (Raman et al. 2014). Haboobs carry and redeposit large amounts of dust, some held down and redistributed by the accompanying rain (see also Chapter 4).

Other ‘cold pool’ phenomena operate and lift dust in three other situations. First, density currents flow down mountain slopes, and some of these raise dust on the plains below. On the southern slopes of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, these events occur about eleven times in a year, between April and December; they have the same spatial scale as haboobs (Emmel et al. 2010). Second, similar density currents may bring momentum and feed dust to the landward phases of sea breezes (discussed later). Third, cold pool atmospheric outflows are the main mechanism for raising dust in the central Sahara (Allen et al. 2013). None of these events leaves an obvious pattern on the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.2.2019 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geologie |

| Schlagworte | Abrasion • Aeolian depositional • aeolian erosion • Aeolian Geomorphology • Aeolian Landforms • Aeolian transportation • bombardment • characteristics of Aeolian processes • cohesion and aggregation • collision of moving particles with stationary ones • collision with solid surfaces • combination of velocity and turbulence • drag • earth sciences • erosion and subsequent deposition • Friction • Geographie • Geography • Geomorphologie • geomorphology • geomorphology on coasts • geomorphology on slopes • Geowissenschaften • gravity is not a driving fact • Guide to Aeolian processes • Lift • Particle Size • physical geography • Physiogeographie • presence of crusts • pre-sort sediment • process of wind removing particles from the surface • Sedimentologie • Sedimentologie u. Stratigraphie • Sedimentology & Stratigraphy • text to Aeolian processes • turbulence changes in wind speed and direction • variations in atmospheric pressure • vegetation micro- and macro topography • wind blows down the pressure gradient • windward versus leeward side of particles |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-94563-8 / 1118945638 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-94563-6 / 9781118945636 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich