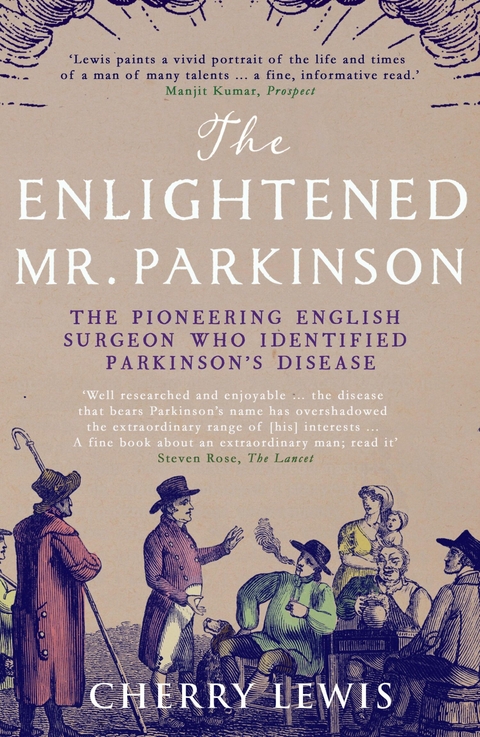

The Enlightened Mr. Parkinson The Enlightened Mr. Parkinson (eBook)

304 Seiten

Icon Books (Verlag)

978-1-78578-179-7 (ISBN)

Cherry Lewis is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Bristol. A geologist by training, she worked in the oil industry as well as in the press office of the University of Bristol before turning her interests to the history of geology. She is the author of The Dating Game: One Man's Search for the Age of the Earth (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

2

The hanged man

It is with the utmost satisfaction I can inform you of a case in which I have been able to restore to life one, who before the institution of your Society, would probably have been numbered with the dead.

John Parkinson, 1777

Transactions of the Royal Humane Society

AT SEVEN O’CLOCK in the evening, on Tuesday 28 October 1777, there was a loud rap at the door of No. 1 Hoxton Square. John Parkinson was urgently summoned to the house of Bryan Maxey who, as the messenger informed him, had hanged himself. John called for James to accompany him and they immediately set out for Maxey’s house about a quarter of a mile away. There they found Maxey who had apparently been dead for half an hour: a coldness had already spread over his body and his jaw had become so fixed that they had to use considerable force to move it. A woman in the house, aware that a reward was offered by the Humane Society to those who resuscitated the dead, had tried with some small success to keep Maxey warm by rubbing his stomach with a flannel. In addition, a neighbour who practised bleeding had taken about eight ounces of blood from Maxey’s arm before the Parkinsons arrived.

Father and son immediately began to give Maxey mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, a new and controversial technique introduced by the Humane Society just a few years previously. James, now 22 and in the final year of his apprenticeship, performed most of the physically taxing work, since John was in poor health. Eventually, as John reported to the Humane Society a few days later, they were successful in returning Maxey to consciousness. After 40 minutes of resuscitation he had given a deep sigh which was followed by an increase in the strength of his pulse. After an hour he was able to breathe without assistance and in another half an hour he regained consciousness. ‘He then complained of an excessive pain in the head,’ explained John, but once given some warm brandy and water, followed by a ‘purging’ broth which enabled him to produce a stool, Maxey was deemed well enough for the Parkinsons to leave.1 Producing a stool was, of course, a vital sign of life.

By the end of a week, Bryan Maxey was completely recovered except for a slight dimness of vision and a feeling of numbness on the right side of his head. He expressed the utmost sorrow for his ‘crime’, as suicide then was, and gratitude to those who were instrumental in restoring him to his wife and children. This satisfactory result was honoured by the Humane Society with the award of its Silver Medal to the young James Parkinson who had worked hard to restore Maxey to life. It became one of his most treasured possessions and he proudly left it to his eldest son in his will.

We are not told why Maxey tried to kill himself, but he appears not to have been alone in the quest to find an end to his misery. According to the Reverend Caleb Fleming,2 a dissenting minister and neighbour of the Parkinsons, there was an epidemic of ‘self murder’ around this time – a period of political and financial instability caused by the American War of Independence.3 As the Reverend Fleming explained, the war had resulted in ‘an alarming shake to public credit’, as well as an ‘obstruction to trade and commerce’ which in turn caused widespread unemployment. The price of food rose sharply and while the rich indulged themselves ‘in every debauchery and extravagance’ imaginable, the poor starved. Unable to cope, many committed suicide: ‘The insolvent and dissatisfied are cruelly laying violent hands on themselves in great numbers,’ lamented Fleming.4

Had Maxey died, the punishment for his crime would have been the forfeiture of all his goods and chattels, as well as those belonging to his wife. So the family would have lost not only a husband and father, but all its worldly goods as well. Even the Reverend Fleming, who considered the heinous crime of self-murder to be an act of High Treason against the sovereignty of the Lord, felt that punishing those left behind was too severe. Instead, he proposed ‘the naked body [of the suicide] should be exposed in some public place’, over which the coroner would deliver an oration on his terrible crime. The body, like that of the murderer, should then be given to the surgeons who would use the parts to demonstrate anatomy to their students. Such a dreadful punishment would have terrified the likes of Maxey, since the idea of dissection after death contravened a belief in the sanctity of the grave where the dead body was supposed to rest undisturbed until Judgement Day when it would be reunited with the soul. If the body was dissected, it would never find its soul, which would wander around in Purgatory forever. Maxey was grateful Parkinson saved him from this fate worse than death.

The Humane Society had been founded just three years earlier by two doctors who were concerned by the number of people wrongly taken for dead and subsequently buried, or dissected, while still alive. The Newgate Calendar, a popular book that reported the crimes, trials and punishments of notorious criminals, quoted the words of a surgeon about to dissect a murderer recently taken down from the gallows:

I am pretty certain, gentlemen, from the warmth of the subject and the flexibility of the limbs, that by a proper degree of attention and care the vital heat would return, and life in consequence take place. But when it is considered what a rascal we should again have among us, that he was hanged for so cruel a murder, and that, should we restore him to life, he would probably kill somebody else. I say, gentlemen, all these things considered, it is my opinion that we had better proceed in the dissection.5

The Humane Society advocated artificial respiration and recommended warming the body, administering stimulants, and bleeding, provided the latter was done with caution. For some years, blowing tobacco smoke into the rectum (fumigation) was also considered beneficial, bellows being used ‘so as to defend the mouth of the assistant’.6 The Society stressed the importance of prompt and prolonged treatment – no case should be abandoned unless vigorous efforts, maintained for at least two hours, had been unsuccessful. Parkinson, however, recommended attempting resuscitation for no less than three or four hours, disdainfully considering it ‘an absurd and vulgar opinion, to suppose persons irrecoverable, because life does not soon make its appearance’.7

Keen to promote these new resuscitation techniques, the Humane Society initially offered money to those rescuing someone from the brink of death. A handsome reward of two guineas was distributed among the first four people to attempt the rescue, and four guineas paid if the person survived. But a scam soon became widespread among the down-and-outs of London: one would pretend to be dead while the other brought him back to life, and they would then share the reward money between them. Consequently, monetary rewards were soon replaced by medals and certificates.

A network of ‘receiving houses’ was set up in and around the Westminster area of London where bedraggled bodies, most of them pulled out of London’s waterways, could be taken for treatment.8 But rare cases of apparent lifelessness also occurred when people were struck by lightning. Ten years after the Bryan Maxey incident, a house in Crabtree Road near Shoreditch Church was badly damaged by lightning and two men, one passing by and one in the house, were struck and seriously injured. The injured passer-by was brought into the damaged house and appeared to be dead, although by the time James Parkinson arrived fifteen minutes later a faint pulse was perceptible. His hands and legs resembled those of a corpse, being excessively cold and of a dark, almost black, colour; his head was bent right back and despite strenuous efforts to bring it forward, it was immovable; his eyes were red, each eye staring in a different direction, which gave him a wild appearance. A large red streak like lightning had appeared down his right side, along with several lesser ones on his legs, the skin in those places being badly scorched. When the man was revived sufficiently to speak, he complained of pain in the head and chest, the latter aggravated by a frequent cough which threw up a lot of blood. His fellow sufferer, the man in the house, had similar symptoms but was not spitting blood. One of the metal buttons on his sleeve had melted, as had the buckle on one shoe where his foot was badly burnt. A red streak, about two inches wide, was evident all down his right side, right arm and on the shins of both legs, forking in a manner similar to lightning and with what appeared to be small ‘sparks’ coming off it; from all these lesions he felt a considerable burning pain.

Parkinson considered the symptoms shown by these men suggested ‘a congestion of blood in the head and lungs’ so he promptly removed six ounces of blood from each patient. They were then put to bed, their burnt legs and hands wrapped in flannels wetted with an ointment composed of sweet oil and ammonia, and a draught was given them for neutralising any acid in the stomach; this was ‘washed down with half a pint of weak brandy and water, as hot as could be drunk’. The two men immediately broke into a sweat and fell into a deep sleep from which they awoke a few hours later apparently recovered, although the man in the house still felt a burning pain where the lightning had ‘so...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.4.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete | |

| Studium ► Querschnittsbereiche ► Geschichte / Ethik der Medizin | |

| Naturwissenschaften | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie | |

| Schlagworte | apothecary • fossils • Georgian London • James Parkinson • medical discovery • Medical History • Neurological Disease • Parkinson's |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78578-179-0 / 1785781790 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78578-179-7 / 9781785781797 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich