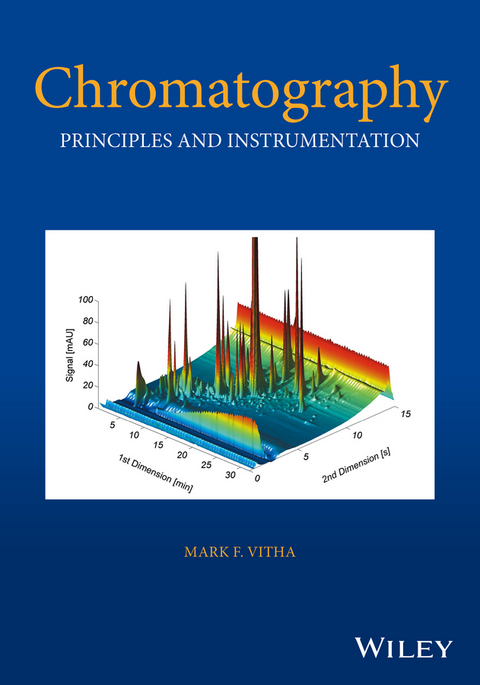

Provides students and practitioners with a solid grounding in the theory of chromatography, important considerations in its application, and modern instrumentation.

- Highlights the primary variables that practitioners can manipulate, and how those variables influence chromatographic separations

- Includes multiple figures that illustrate the application of these methods to actual, complex chemical samples

- Problems are embedded throughout the chapters as well as at the end of each chapter so that students can check their understanding before continuing on to new sections

- Each section includes numerous headings and subheadings, making it easy for faculty and students to refer to and use the information within each chapter selectively

- The focused, concise nature makes it useful for a modular approach to analytical chemistry courses

Mark F. Vitha is currently a Professor at Drake University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. He is the series editor for The Chemical Analysis Series (Wiley) and is a co-editor of the book High Throughput Analysis for Food Safety (Wiley, 2014). He has been named as a Levitt Teacher of the Year, a Windsor Professor of Science, and a Ronald D. Troyer Research Fellow at Drake.

Provides students and practitioners with a solid grounding in the theory of chromatography, important considerations in its application, and modern instrumentation. Highlights the primary variables that practitioners can manipulate, and how those variables influence chromatographic separations Includes multiple figures that illustrate the application of these methods to actual, complex chemical samples Problems are embedded throughout the chapters as well as at the end of each chapter so that students can check their understanding before continuing on to new sections Each section includes numerous headings and subheadings, making it easy for faculty and students to refer to and use the information within each chapter selectively The focused, concise nature makes it useful for a modular approach to analytical chemistry courses

Mark F. Vitha is currently a Professor at Drake University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. He is the series editor for The Chemical Analysis Series (Wiley) and is a co-editor of the book High Throughput Analysis for Food Safety (Wiley, 2014). He has been named as a Levitt Teacher of the Year, a Windsor Professor of Science, and a Ronald D. Troyer Research Fellow at Drake.

Preface

Chapter 1: Fundamentals of Chromatography

1.1 Theory

1.2 Band Broadening

1.3 General Resolution Equation

1.4 Peak symmetry

1.5 Key Operating Variables

1.6 Instrumentation

1.7 Practice of the Technique

1.8 Emerging Trends and Applications

1.9 Summary

Problems

Bibliography

References

Chapter 2: Gas Chromatography

2.1 Theory of Gas Chromatographic Separations

2.2 Key Operating Variables that Control Retention

2.3 Gas Chromatography Instrumentation

2.4 A More Detailed Look at Stationary Phase Chemistry: Kovats Indices and McReynolds Constants

2.5 Gas Chromatography in Practice

2.6 A "Real-World" Application of Gas Chromatography

2.7 Summary

Problems

Bibliography

References

Chapter 3: Liquid Chromatography

3.1 Examples of Liquid Chromatography Analyses

3.2 Scope of liquid chromatography

3.3 History of LC

3.4 Modes of Chromatography

3.5 HPLC Instrumentation

3.6 Specific Uses and Advances/Trends in Chromatography

3.7 Application of LC -- Analysis of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Groundwater

3.8 Summary

Problems

References

Index

"Mark Vitha has written a book that will appeal to students, teachers, and perhaps professional analysts who need a refresher in the fundamentals of chromatography. The book consists of three sections of about equal length dealing with separation theory, gas chromatography (GC), and liquid chromatography (LC). The section on theory is especially strong. Vitha is an experienced educator who understands the undergraduate audience and explains concepts clearly. He uses analogies to help students with abstract ideas, something I have seen little of in the sciences. He also freely uses ideas and terms from thermodynamics that can be grasped by students who have studied physical chemistry".

"Graduate students might want to use this book, with additional depth provided by their instructors and current and classic papers (many are referenced). Graduate students need more depth in areas such as solvent theory and the selection of solvents, for example, than is given in this book".

"I taught instrumental methods to undergraduate students for many years using encyclopedic full-course texts. I wish there had been as fine a pedagogical tool as this more-focused new textbook at that time". (LC/GC- December 16)

CHAPTER 1

Many “real-world” samples are mixtures of dozens, hundreds, or thousands of chemicals. For example, medication, gasoline, blood, cosmetics, and food products are all complex mixtures. Common analyses of such samples include quantifying the levels of drugs – both legal and illegal – in blood, identifying the components of gasoline as part of an arson investigation, and measuring pesticide levels in food.

FUNDAMENTALS OF CHROMATOGRAPHY

Chromatography is a technique that separates the individual components in a complex mixture. Fundamental intermolecular interactions such as dispersion, hydrogen bonding, and dipole–dipole forces govern the separations. Once separated, the solutes can also be identified and quantified. Because of its ability to separate, quantify, and identify components, chromatography is one of the most important instrumental methods of analysis, both in terms of the number of instruments worldwide and the number of analyses conducted every day.

1.1 THEORY

Chromatography separates components in a sample by introducing a small volume of the sample at the start, or head, of a column. A mobile phase, either gas or liquid, is also introduced at the head of the column. When the mobile phase is a gas, the technique is referred to as gas chromatography (GC) and when it is a liquid, the technique is called liquid chromatography (LC). Unlike the sample, which is injected as a discrete volume, the mobile phase flows continuously through the column. It serves to push the molecules in the sample through the column so that they emerge, or “elute” from the other end.

Two particular modes of LC and GC, known as reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) and capillary gas chromatography, account for approximately 85% of all chromatographic analyses performed each day. Therefore, we focus on these two techniques here and leave discussions of specific variations to the chapters that describe LC and GC in greater detail.

In GC, the mobile phase, which is typically He, N2, or H2 gas, is delivered from a high-pressure gas tank. The gas flows through the column toward the low-pressure end. The column contains a stationary phase. In capillary GC, the stationary phase is typically a polymer film that is 0.25–5 µm thick (see Figure 1.1a). It is coated on the interior walls of a fused silica capillary column with an inner diameter of approximately 0.5 mm or smaller. The column is usually 10–60 m (30–180 ft) long.

Figure 1.1 Representations of typical capillary gas (a) and liquid (b) chromatography columns. Figure (c) is a depiction of a cross section of a porous particle (shaded areas represent the solid support particles, white areas are the pores, and the squiggles on the surface are bonded alkyl chains. Figure (d) is an scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of actual 3 µm liquid chromatography porous particles. Note that the lines across the particle diameters have been added to the image and are not actually part of particles. (Source: Alon McCormick and Peter Carr. Reproduced with permission of U of MN.). It is worth taking time to note the different dimensions involved. For the GC columns, they range from microns (10−6 m) for the thickness of the stationary phase, to millimeters (10−3 m) for the column diameter, up to tens of meters for the column length. Note also that LC columns are typically much shorter than GC columns (centimeter versus meter).

RPLC is the most common mode of liquid chromatography. In RPLC, the mobile phase is a solvent mixture such as water with acetonitrile (CH3CN) that is forced through the column using high-pressure pumps. The column is typically made of stainless steel, has an inner diameter of 4.6 mm or smaller, and is only 20–250 mm (1–10 in.) in length (see Figure 1.1b). However, unlike most GC columns, most LC columns are packed with tiny spherical particles approximately 5 µm in diameter or smaller, as shown in Figure 1.1c and d. When rubbed between your fingers, the particles feel like talc or other fine powders. The particles are not completely solid, but rather are highly porous, with thousands of pores in each particle. The pores create cavities akin to caves within the particle. The pores create a large amount of surface area inside the particles. A stationary phase, typically an alkyl chain 18 carbon atoms long, is bonded to the surface of these pores. A more specific discussion of the important aspects of these particles, and variations in the kinds of stationary phases bonded to them, is provided in Chapter 3. For now, it is simply important to have an image of a stainless steel column packed with very fine porous particles that have an organic-like layer bonded to the surface of the pores.

Some of the important RPLC and capillary GC column characteristics are summarized in Table 1.1. We also point out here that a chromatographic analysis is conducted with an instrument called a chromatograph and results in a chromatogram, which is a plot of the detector's response versus time (see Figure 1.2). Subsequent sections describe how retention and separation of molecules are quantified.

Table 1.1 Common RPLC and GC Characteristics

| RPLC | GC (open tubular) |

| Column construction | Stainless steel | Quartz with a polyimide coating |

| Column length | 20–250 mm | 10–60 m |

| Column inner diameter | 2.1– 4.6 mm | 0.1–0.5 mm |

| Particle composition | Porous silica (SiO2) particles | No particles – open tube |

| Particle size | 1.8–5 µm | No particles – open tube |

| Mobile phase | Solvent mixture (e.g., water mixed with acetonitrile) | He, N2, or H2 |

| Stationary phase location | Alkyl chains (C-8 and C-18) bonded to particle surface | Liquid-like polymer film bonded to capillary walls |

| Stationary phase chemistry | Relatively nonpolar and organic in nature | Polysiloxane polymer derivatized with organic moieties |

Figure 1.2 An example of a chromatogram – a plot of signal versus time – measured using a chromatograph (the instrument). Each peak represents a different solute that emerges from the column at a different time than the others. The peak width and height are related to the amount of each solute present.

1.1.1 Component Separation

Different types of molecules are separated within the column because they have different strengths of intermolecular interactions with the mobile and stationary phases. To help understand chromatographic separations, we first use a simplified model of liquid chromatography with water as the mobile phase and octane (C8H18) as the stationary phase. Imagine that a mixture of toluene and phenol is introduced as solutes into the mobile phase as depicted in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 This figure depicts the behavior of phenol and toluene (solutes) partitioning between water and octane (bulk solvents). The water and octane serve as models for the mobile and stationary phases, respectively, in liquid chromatography. The left image depicts the system right after solutes are added to the aqueous phase before equilibrium is established. Once equilibrium is established (right), more toluene than phenol partitions into the nonpolar octane phase. Similarly, more phenol resides in the water due to hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions.

In this static image, given enough time, the solute molecules diffuse through the water and into the octane. They eventually reach equilibrium, being distributed to different extents between the water (mobile) and octane (stationary) phases. This equilibrium process is described in Equation 1.1

with the associated equilibrium constant

where “A” represents a specific analyte such as phenol or toluene, and K, by IUPAC definition, is known as the distribution constant. Many chromatographers refer to it as the partition coefficient or distribution coefficient. We will treat all of these as synonymous in this and the following chapters.

Because phenol is more polar than toluene and capable of hydrogen bonding with water, it does not partition into the octane to the extent that the toluene does. When looked at from a temporal perspective, phenol molecules spend less time in the octane, on average, than do the toluene molecules, which are attracted to the octane by dispersion interactions. It is important to understand that phenol is also attracted to the octane by dispersion interactions, and in fact, toluene is attracted to water through dispersion and dipole-induced dipole interactions. However, because phenol can participate in dipole–dipole and hydrogen-bonding interactions with water, and toluene cannot, phenol has a greater affinity for the aqueous phase than does toluene. As a consequence, phenol stays in the water more and partitions less into the stationary phase than does toluene.

It is clear from Figure 1.3 that what was once a mixture of an equal number of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.8.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Chemie ► Analytische Chemie |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Applications • Band broadening • Biowissenschaften • Cell & Molecular Biology • chemical engineering • Chemie • Chemische Verfahrenstechnik • Chemistry • Chromatographie • Chromatographie / Trennverfahren • Chromatography / Separation Techniques • Gas Chromatography • Golay • Life Sciences • Liquid chromatography • <p>Chromatography • textbook</p> • Theory, Practice • Trennverfahren • undergraduate • Van Deemter • Zell- u. Molekularbiologie |

| ISBN-13 | 9781119270904 / 9781119270904 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich