First global comprehensive review of this ecologically diverse set of species

- Conservation of antelopes who serve as prey is critical to ensure conservation of corresponding predator species

- Ecological diverity of these species ensures that conservation issues from Antelopes can be easily applied to other species

- Includes state of the art approaches such as molecular techniques and the application of landscape genetics

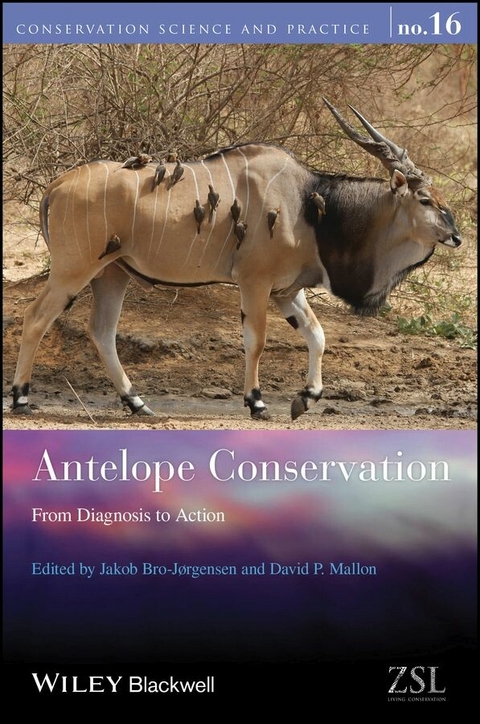

Antelopes constitute a fundamental part of ecosystems throughout Africa and Asia where they act as habitat architects, dispersers of seeds, and prey for large carnivores. The fascication they hold in the human mind is evident from prehistoric rock paintings and ancient Egyptian art to today's wildlife documentaries and popularity in zoos. In recent years, however, the spectacular herds of the past have been decimated or extripated over wide areas in the wilds, and urgent conservation action is needed to preserve this world heritage for generations to come.As the first book dedicated to antelope conservation, this volume sets out to diagnose the causes of the drastic declines in antelope biodiversity and on this basis identify the most effective points of action. In doing so, the book covers central issues in the current conservation debate, especially related to the management of overexploitation, habitat fragmentation, disease transmission, climate change, populations genetics, and reintroductions. The contributions are authored by world-leading experts in the field, and the book is a useful resource to conservation scientists and practitioners, researchers, and students in related disciplines as well as interested lay people.

Jakob Bro-Jorgensen, Department of Evolution, Ecology and Behaviour, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. David P. Mallon, Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, Manchester, Metropolitan University, United Kingdom.

Contributors vii

Preface and Acknowledgements x

Foreword xiii

Richard D. Estes

1 Our Antelope Heritage - Why the Fuss? 1

Jakob Bro-Jørgensen

2 Conservation Challenges Facing African Savanna Ecosystems 11

Adam T. Ford, John M. Fryxell, and Anthony R. E. Sinclair

3 Population Regulation and Climate Change: The Future of Africa's Antelope 32

J. Grant C. Hopcraft

4 Interspecific Resource Competition in Antelopes: Search for Evidence 51

Herbert H. T. Prins

5 Importance of Antelope Bushmeat Consumption in African Wet and Moist Tropical Forests 78

John E. Fa

6 Opportunities and Pitfalls in Realising the Potential Contribution of Trophy Hunting to Antelope Conservation 92

Nils Bunnefeld and E. J. Milner-Gulland

7 Antelope Diseases - the Good, the Bad and the Ugly 108

Richard Kock, Philippe Chardonnet, and Claire Risley

8 Hands-on Approaches to Managing Antelopes and their Ecosystems: A South African Perspective 137

Michael H. Knight, Peter Novellie, Stephen Holness, Jacobus du Toit, Sam Ferreira, Markus Hofmeyr, Christina Grant, Marna Herbst, and Angela Gaylard

9 DNA in the Conservation and Management of African Antelope 162

Eline D. Lorenzen

10 Biological Conservation Founded on Landscape Genetics: The Case of the Endangered Mountain Nyala in the Southern Highlands of Ethiopia 172

Anagaw Atickem, Eli K. Rueness, Leif E. Loe, and Nils C. Stenseth

11 The Use of Camera-Traps to Monitor Forest Antelope Species 190

Rajan Amin, Andrew E. Bowkett, and Tim Wacher

12 Reintroduction as an Antelope Conservation Solution 217

Mark R. Stanley Price

13 Desert Antelopes on the Brink: How Resilient is the Sahelo-Saharan Ecosystem? 253

John Newby, Tim Wacher, Sarah M. Durant, Nathalie Pettorelli, and Tania Gilbert

14 The Fall and Rise of the Scimitar-Horned Oryx: A Case Study of Ex-Situ Conservation and Reintroduction in Practice 280

Tim Woodfine and Tania Gilbert

15 Two Decades of Saiga Antelope Research: What have we Learnt? 297

E. J. Milner-Gulland and Navinder J. Singh

16 Synthesis: Antelope Conservation - Realising the Potential 315

Jakob Bro-Jørgensen

Appendix: IUCN Red List Status of Antelope Species April 2016 329

Index 332

1

Our Antelope Heritage – Why the Fuss?

Jakob Bro‐Jørgensen

Mammalian Behaviour and Evolution Group, Department of Evolution, Ecology and Behaviour, Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Introduction

Why a book dedicated to antelope conservation? Our planet has witnessed a decrease of more than 50% in its vertebrate populations since 1970, and this drastic decline has hit antelopes particularly hard, according to the Living Planet Index (BBC, 2008; McLellan, 2014; see also Craigie et al., 2010). Many will agree that antelopes constitute an outstanding aspect of the world’s biodiversity and that the prospect of losing this heritage is a concern in its own right. A savanna bereft of flickering herds of gazelles (Figure 1) or a rainforest where duikers no longer lurk in the understorey may be likened to bodies that have lost their souls. But leaving subjective sentiments aside, antelopes are also of fundamental importance for the functioning of many ecosystems across Africa and Asia. They have important roles as architects of habitats, as dispersers of seed, as the prey base for endangered carnivores and indeed in nutrient cycling in general (Sinclair & Arcese, 1995; Sinclair et al., 2008; Gallagher, 2013). Maintaining healthy antelope populations is therefore vital for the management of many ecosystems, and the motivation for this book comes from an urgent concern not only at the species level but also relating to wider repercussions at the ecosystem level.

Figure 1 Thomson gazelles and impalas in Maasai Mara National Reserve, Kenya

(© Jakob Bro‐Jørgensen).

Antelopes moreover provide a well‐suited model to obtain insights into the operation of threat processes affecting wildlife populations more generally. Because they share the same basic biology, yet display a striking variation in habitats and threats, this species‐rich group presents an extraordinary opportunity to pinpoint how human impact on wildlife populations depends on the interaction between threats and specific species traits. Many of the issues facing antelopes are central to the current conservation debate, including the sustainable use of wildlife (for meat and trophies), protection of migratory as well as highly habitat‐specific species in a world of climate change and habitat fragmentation, and the coexistence of wildlife with people and their livestock without conflict. Typically, antelope conservation takes place in developing countries with growing human populations and severely under‐resourced wildlife authorities, which brings the issue of how to integrate conservation and development to the forefront. Valuable long‐term data sets are present for several antelope species, placing them in a strong position to provide some general lessons for conservation biology, especially in relation to the particular challenge of preserving large mammals (MacDonald et al., 2013).

However, following a surge in pioneering field studies of many antelope species in the 1960s and 1970s, the reality is that antelope research seems to have lost its general appeal, and the attention from the general public is modest compared to that received by many of their mammalian relatives, such as carnivores and primates, which are widely seen as more charismatic. This book is intended to reinvigorate the interest in antelope research and give a deeper understanding of the threat drivers facing antelopes today, thereby providing a basis for reflection on common best practices in conservation. As a background, this introductory chapter will first take an evolutionary perspective to understanding the ecological importance of global antelope biodiversity and then outline the current conservation status of this world heritage.

Antelopes – an evolutionary success story … so far

A green world presents a tremendous opportunity for the evolution of efficient plant‐eaters, and here antelopes have been an extraordinary success story. A major evolutionary breakthrough took place in the Eocene some 50 Myrs BP when the compartmentalized ruminant stomach evolved (Fernández & Vrba, 2005). This enabled a more efficient breakdown of fibrous plant material by chewing cud and using microbial symbionts to digest cellulose. The antelopes are members of the ruminant family Bovidae, characterized by permanent horns consisting of a bone core covered by a sheath of keratin. The first known bovid fossil, Eotragus, dates back to the early Miocene some 20 Myrs BP (Gentry, 2000; Fernandez & Vrba, 2005), and since then, an astonishing adaptive radiation has taken place as bovid species have evolved to occupy a wide range of ecological niches. The majority of these species are antelopes: 88 extant species are represented by 14 species in Asia and 75 species in their main stronghold in Africa, with only the dorcas gazelle (Gazella dorcas) found on both continents. Antelopes vary in size from the 1.5 kg of a royal antelope (Neotragus pygmaeus) (Plate 3) to nearly a ton in a full‐grown giant eland bull (Tragelaphus derbianus) (cover).

So what distinguishes antelopes? Treating antelopes as a group is questionable from a strict evolutionary perspective because it violates the ideal of keeping together all species descending from a given distinctive ancestor. The group is created by cutting off two distinct monophyletic branches from the bovid tree: (i) the wild oxen Bovini, characterized by their heavier build and water‐dependence, and (ii) the wild goats and sheep Caprinae, characterized by their extreme adaptation to rocky habitats (Figure 2). However, antelopes are not defined only by what they are not (i.e., as a bovid that is neither an oxen nor a goat). They can be succinctly described as horned ruminants lightly built for swift movement in habitats with predominantly even ground. This has resulted in a characteristic graceful and elegant morphology, often adorned with spectacular ornaments and weapons due to strong sexual selection in the more social species (Stoner et al., 2003; Bro‐Jørgensen, 2007).

Figure 2 The evolution within Bovidae since the divergence from deer 32 million years ago (for common names, see the Appendix). Bar indicates one million years.

Based on Fernández & Vrba 2005; drawn in Dendroscope, Huson & Scornavacca 2012.

The broad array of ecological adaptations in antelopes is apparent when considering the variety between the 12 tribes (Plates 1, 2, & 3). The spiral‐horned antelopes of Africa Tragelaphini (elands, kudus, nyalas and allies), together with their Asian relatives Pseudorygini (saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) and Boselaphini (nilgai Boselaphus tragocamelus, four‐horned antelope Tetracerus quadricornis), represent a highly diverse ancient line from within which the wild oxen descended. Except for the browsing saola, they are mixed feeders; that is, feeding on both browse and grass. They vary more than tenfold in size and are found from dense forests (bongo Tragelaphus eurycerus, saola) to semi‐deserts (common eland Tragelaphus oryx), and from swamps (sitatunga Tragelaphus spekii) to mountains (mountain nyala Tragelaphus buxtoni). Other mixed feeders include the arid‐adapted gazelles Antilopini which span from hot to rather cold regions, and the horse antelopes Hippotragini, which predominantly graze and occur from relatively moist savannas (roan Hippotragus equinus and sable antelope Hippotragus niger) to semi‐deserts (oryxes) and deserts (addax Addax nasomaculatus). Both the latter tribes have representatives in Africa as well as Asia. Also mixed‐feeders, the African impala (Aepyceros melampus) and rhebok (Pelea capreolus) are the only living representatives of the tribes Aepycerotini and Peleini respectively. The grazing tribes include the reduncines Reduncini (lechwes, reedbucks and allies), adapted to relatively moist savannas and wetlands, and the alcelaphines Alcelaphini (wildebeests and allies), adapted to drier savannas; both are exclusively African. The Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii), the only representative of the caprine‐related Pantholopini, also feeds on grass, as well as herbs, on the often snowy steppes of the Tibetan Plateau. Smaller antelopes include the duikers Cephalophini, which are adapted to the ecology of African forests, where they feed on high‐quality browse and fruits, and the dwarf antelopes Neotragini which are ecologically diverse, mainly browsers and frugivores, but some also feeding on grass (notably the oribi Ourebia ourebi), and inhabiting a wide range of habitats spanning from forests (royal antelope) and thickets (suni Neotragus moschatus, dik‐diks), to rocky outcrops (klipspringer Oreotragus oreotragus, beira Dorcatragus megalotis) and fairly open savannas (oribi); several neotragines are actually likely to be more closely related to gazelles than to the genus Neotragus. In contrast to the gregarious species of the open land, the smaller species in dense habitats are usually solitary or found in groups of minimal size (Jarman, 1974; Brashares et al., 2000).

Antelopes as an integral part of the structure and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.6.2016 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Conservation Science and Practice |

| Conservation Science and Practice | Conservation Science and Practice |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geologie | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Africa • Ãkologie / Tiere • Animal ecology • Animal Science & Zoology • Antelope • Biowissenschaften • Bovidae • conservation • Conservation Science • Developing Countries • Ecology • Herbivore • Life Sciences • mammals • Naturschutzbiologie • Ökologie / Tiere • tropics • Ungulate • Zoologie |

| ISBN-13 | 9781118409626 / 9781118409626 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich