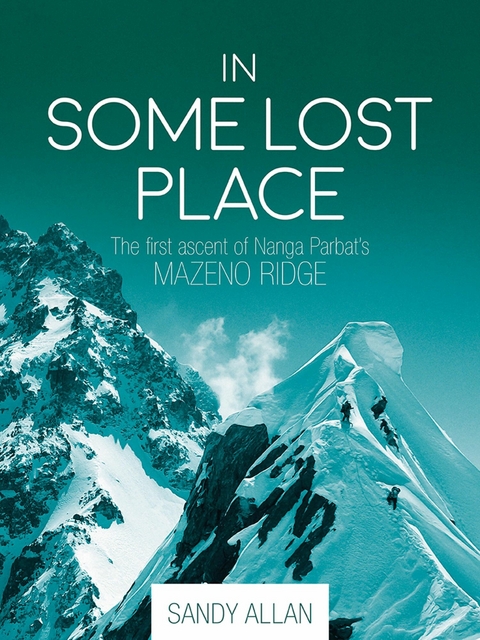

In Some Lost Place (eBook)

Vertebrate Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-910240-38-0 (ISBN)

In the summer of 2012, a team of six climbers set out to attempt the first ascent of one of the great unclimbed lines of the Himalaya - the giant Mazeno Ridge on Nanga Parbat, the world's ninth highest mountain. At ten kilometres in length, the Mazeno is the longest route to the summit of an 8,000-metre peak. Ten expeditions had tried and failed to climb this enormous ridge. Eleven days later two of the team, Sandy Allan and Rick Allen, both in their late fifties, reached the summit. They had run out of food and water and began hallucinating wildly from the effects of altitude and exhaustion. Heavy snow conditions meant they would need another three days to descend the far side of the 'killer mountain'. 'I began to wonder whether what we were doing was humanly possible. We had climbed the Mazeno and reached the summit, but we both knew we had wasted too much energy. In among the conflicting emotions, the exhaustion and the elation, we knew our bodies could not sustain this amount of time at altitude indefinitely, especially now we had no water. The slow trickle of attrition had turned into a flood; it was simply a matter of time before our bodies stopped functioning. Which one of us would succumb first?' In Some Lost Place is Sandy Allan's epic account of an incredible feat of endurance and commitment at the very limits of survival - and the first ascent of one of the last challenges in the Himalaya.

– Chapter 2 –

Mentors

Driving through the Pakistani countryside, I rested my head on the window and thought of all the people who, over the years, had got me here. Mal Duff had been there at the start of it all. He was part of the reason I was on this bus now. I remembered waiting for another ride, from London’s Victoria station to Chamonix for one of Mal’s legendary climbing courses. He had sent me joining instructions through the post, because that’s how things were done in the 1970s. We were to make our own way to London and meet at an appointed hour under Victoria’s huge departures board. Mal would gather up his latest recruits and we’d all drive off together – only it didn’t work out that way.

As a nineteen-year-old lad, I was looking forward to my first season in the Alps. I’d learned the basics of rock climbing near my home in the Cairngorms. I had spent long evenings poring over books by famous climbers, from Albert Frederick Mummery and Edward Whymper to Gaston Rébuffat and Lionel Terray. My biggest inspiration, as a Scot, was the Edinburgh climber Dougal Haston who, in 1966, had climbed a new route on the north face of the Eiger after John Harlin had fallen to his death. Then, in 1975, Haston survived an unplanned bivvy above 8,000 metres on the south-west face of Everest with Doug Scott. I knew that both of them had climbed with a fellow called Chris Bonington, who seemed good at getting media attention and had written a book called I Chose to Climb, which was open and honest, inspiring and quite different to other mountaineering books of that time. Doug, who looked a bit like John Lennon, and Dougal were all over the news thanks to their success on Everest. Their mountaineering achievements inspired a generation – my generation.

So I found myself walking across the concourse at Victoria where a number of other youths waited for Mal under the departures board. We introduced ourselves, sniffing round each other in the way that young men do, trying not to appear like we cared, but caring a great deal. They seemed far more streetwise than me. Some had sprouted immature beards and had grown up in the city. I felt very much the country bumpkin. This was my first adventure away from home. Even the train down to London had been a novel experience. The only other train I’d been on was the small puffer we had at Balmenach Distillery, where my father worked.

The engine was owned and maintained by the distillery and ran down to the main line at Cromdale where it would pick up wagons left in a siding. The little engine would hitch up the big wagons, loaded with tons of coal or barley, and pull them back up to the distillery, where they were unloaded by men with shovels. The barley was turned to malt, a vital ingredient for the final amber spirit; the coal powered it all. With my twin brother Gregor and younger sister Eunice, I’d hitch rides on the train to visit the local shop and play with other kids.

Balmenach is an excellent whisky, a ‘single malt’ that without doubt is one of the very best from Speyside. Not only was my dad a distiller, so was his father before him and almost all my uncles on that side of the family. My mother was from farming stock and we have many relations who own large parts of the Black Isle and drive those big green John Deere tractors that delay motorists driving along the A9.

When Greg and I were born, our parents were running the distillery at Dalwhinnie, in a wonderfully isolated spot in the Cairngorms often mentioned on the news as the coldest place in Britain. My dad had driven Mum to Raigmore Hospital in Inverness when we arrived on 8 September, with me emerging fifteen minutes ahead of my brother. We have been good buddies since birth and have an uncanny connection to each other. To this day, one of us can pick up the phone to call the other and be connected without the phone ringing at the other end of the line. We have even gone out to buy ourselves the same new car – the exact same model, same colour and everything – without even hinting to the other that we were buying a new vehicle.

Greg now lives in the Channel Islands. He doesn’t climb but the bond we have gives me fantastic strength. He left school with ambitions to become a chartered accountant while I wanted to be a shepherd and whisky distiller. He now runs his own company advising large investment houses and multinational companies, and sits on the boards of huge financial institutions giving expensive and apparently sound advice. I am a shepherd in a way, shepherding people in the mountains, rather than sheep. We each have two daughters and all are the best of friends.

So there I was, a naive Highland laddie, standing in Victoria station daring to speak to these cosmopolitan youths apparently accustomed to crowds and swearing broadly, something I’d not heard at home. British Rail staff, many of them Afro-Caribbean, moved around us, the first black people I’d seen who weren’t on television. My Karrimor ‘Haston Alpiniste’ rucksack showed the wear and tear from years of Munro-bagging and other adventures in the Scottish Highlands, but otherwise I felt I was the novice of the party.

Hours later an older man with a proper beard approached us. He was quite skinny and had a fine, clear Edinburgh accent – Mal Duff. As he talked his arms waved. Our vehicle, supposed to transport us to Chamonix, had broken down. There were apologies galore. We were to board a train, pay for it ourselves, go to Dover, catch a ferry and then continue to Paris, where we would transfer by Metro to another station on the other side of Paris and catch another train to Saint-Gervais and so eventually on to Chamonix. He had no idea what trains to catch, which platforms they left from or a single clue about times. He winged it all the way, something I quickly learned was typical of Mal.

It was a mad but exciting rush between platforms, all of us running after him like chicks, bent double under our huge rucksacks. I was totally exhausted, having not slept since leaving Scotland, and I kept falling asleep, sitting on train floors since the seats always seemed to be occupied. Eventually, starving and bedraggled, we all tumbled out on to the platform in Chamonix to be told that it was only a mile or so to walk – in blazing sunshine – to the campsite.

This, it turned out, was on the wonderfully infamous Snell’s Field on the outskirts of Chamonix. The place is a legend in Alpine-climbing tales, a wild camping area in more ways than one and still home to a famous boulder called the Pierre d’Orthaz. (We all thought it was named after some guy called Pierre, maybe the guy who owned the field.) Mal had a team of illustrious British climbers working for him, none of whom were qualified guides, at least not then. There were tents pitched haphazardly and a kitchen area with gas stoves, pans and a water butt. We were given a quick introduction to the camping area, our tents and sleeping places, and were handed mugs of hot tea with a sachet of powdered milk.

I hid my passport in my Blacks sleeping bag, something every British kid had at the time, and we walked into Chamonix for our first beer in the famous Bar Le National, a longstanding bastion of British climbing. By the bar sat the owner, a well-rounded man called Maurice Simond who seemed almost always half asleep. He had two wonderful daughters, Sylvie and Christine, who were both very welcoming. None of us could afford to buy more than one drink there and we soon learned to go to the supermarket and buy cheap bottles of beer before meeting up at the bar, where we would buy one beer from Maurice, drink it and then top up our glasses under the table. Maurice knew what we were up to but let it go, a kind man and welcoming to all British climbers. When he passed away many years later I wrote to the British Mountaineering Council suggesting we do something on behalf of British climbers to mark his passing. A little brass plaque was fixed to the wall of the Bar Le National recalling his hospitality ‘with thanks from all British alpinists’.

For a young man from the Highlands, Chamonix was an eye-opening experience. The girls were beautiful, always in their summer dresses, their legs tanned and long, and speaking English with French accents. Surrounding Chamonix, the mountains and rock faces were incredible; one could not look at them and not be inspired to climb. It was an amazing town back then, overflowing with free spirits. Everyone seemed to climb or live to be in the mountains; everyone I met seemed in some way unconventional. Real jobs, proper mundane work, was something to be put off until later. Years later. Most people had good enough climbing equipment and clothing, some even had good off-piste ski-mountaineering skis and climbed in the Himalaya, but otherwise we all avoided spending money on unnecessary stuff. Hitchhiking was how we travelled, or by taking possession of someone’s old banger of a car. Living on a shoestring was the norm.

Our ‘guides’ took us to the Bossons Glacier, in those days much closer to the road, and after a short walk through the pine-scented forest we arrived at the ice. (These days, with climate change and glacial retreat, it’s no longer considered a safe training venue.) I had never really used ice climbing tools before. I had an axe with an adze and an axe with a hammer, and some long nail-like ice screws called ‘warthogs’ and some clever new tubular screws introduced by a man called Yvon Chouinard. I wrapped long neoprene straps across my boots and through the rings on my crampons in a very deliberate pattern. Strapping on crampons was considered an art form. Then, with the buckles done up, I stomped along the ice.

It’s the most fantastic feeling, being able to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.7.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Schlagworte | cathy o'dowd • Doug Scott • Hermann Buhl • Mazeno Ridge • Nanga Parbat • Reinhold Messner • Rick Allen |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-38-9 / 1910240389 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-38-0 / 9781910240380 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich