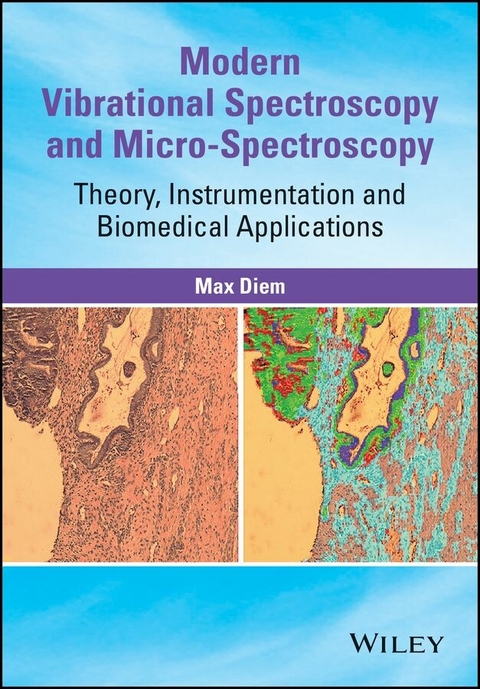

Modern Vibrational Spectroscopy and Micro-Spectroscopy (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-82498-6 (ISBN)

Max Diem Northeastern University, USA

"Graduate students who are entering the complex and rapidly developing field of vibrational biospectroscopy or microscopy would find this book useful. Experienced scientists and instructors in vibrational spectroscopy and microspectroscopy will also find this book a valuable reference for their work." (Optics & Photonics News, 1 January 2016)

Part I

Modern Vibrational Spectroscopy and Micro-spectroscopy: Theory, Instrumentation and Biomedical Applications

Introduction

I.1 Historical Perspective of Vibrational Spectroscopy

The subject of this monograph, vibrational spectroscopy, derives its name from the fact that atoms in molecules undergo continuous vibrational motion about their equilibrium position, and that these vibrational motions can be probed via one of two major techniques: infrared (IR) absorption spectroscopy and Raman scattering, and several variants of these two major categories. IR spectroscopy experienced a boon in the years of World War II, when the US military was involved in an effort to produce and characterize synthetic rubber. Vibrational spectroscopy, for which industrial application guides were published as early as 1944 [1], turned out to be a fast and accurate way to identify different synthetic products. The rapid growth of the field of vibrational spectroscopy can be gauged by the fact that by the mid-1940s, the field was firmly established as a scientific endeavor, and the volume “Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure” by Herzberg (one volume of a trilogy of incredibly advanced treatises on molecular spectroscopy [2]) reported infrared and Raman results on hundreds of small molecules. Similarly, the earliest efforts to use infrared spectroscopy as a means to distinguish normal and diseased tissue – the subject of Part II of this book – were reported by Blout and Mellors [3] and by Woernley [4] by the late 1940s and early 1950s. In the 1960s, the petroleum industry added another industrial use for these spectroscopic techniques when it was realized that hydrocarbons of different chain lengths and degrees of saturation produced distinct infrared spectral patterns, and for the first time, computational methods to understand, reproduce, and predict spectral patterns were introduced [5]. By then, commercial scanning infrared spectrometers were commercially available.

The 1970 produced another boon when commercial Fourier transform (FT) infrared spectrometers became commercially available, and gas lasers replaced the mercury arc lamp as excitation source for Raman spectroscopy. Before lasers, Raman spectroscopy was a somewhat esoteric technique, since large sample volumes and a lot of time were required to collect Raman data with the prevailing Hg arc excitation sources. Yet, after the introduction of laser sources, Raman spectra could be acquired rapidly and as easily as infrared spectra. After the introduction and wide acceptance of interferometry, infrared spectroscopy became the method of choice for many routine and quality control applications. During the ensuing decade, the field of vibrational spectroscopy blossomed at a phenomenal rate, and it is safe to state that no other spectroscopy grew at such a pace than vibrational spectroscopy, perhaps with the exception of nuclear magnetic resonance techniques. Other spectroscopic methods, such as ultraviolet/visible (UV/vis), microwave, or electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy certainly profited from theoretical and technical advances; however, in vibrational spectroscopy, the sensitivity of the measurements increased by orders of magnitude while the time requirements for data acquisition dropped similarly.

After the introduction of tunable, high power, and pulsed lasers, not only were faster and more sensitive techniques developed (for example, resonance Raman and time-resolved techniques), but also, entirely new spectroscopic methods were discovered, among them a number of “non-linear” Raman techniques (such as Hyper-Raman and Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering, CARS) in which the effect depends non-linearly on the laser field strength. Dramatic progress was also achieved in IR spectroscopy, due to the advent of infrared lasers and further refinements of interferometric methods.

Aside from small molecule applications of vibrational spectroscopy, the past three decades have seen an ever increasing use of vibrational spectroscopy in biophysical, biochemical, and biomedical studies. This field has enormously enhanced the ability to determine solution conformations of biological molecules, their interaction and even reaction pathways. All major classes of biological molecules, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, exhibit vibrational spectra that are enormously sensitive to structure and structural changes, and thousands of research papers have been published demonstrating the value of these methods for the understanding of biochemical processes.

With the advent of vibrational micro-spectroscopic instruments, that is, infrared or Raman spectrometers coupled to optical microscopes, cell biological and medical application of vibrational spectroscopy was practical since the spatial resolution in Raman and infrared absorption microscopy is sufficient to distinguish, by spectral features, parts of cells and tissue. These methods are poised to enter the medical diagnostic field as inherently reproducible and objective tools. This monograph will provide an introduction to many of these fields mentioned above.

I.2 Vibrational Spectroscopy within Molecular Spectroscopy

Molecular spectroscopy is a branch of science in which the interactions of electromagnetic radiation and matter are studied. While the theory of these interactions itself is the subject of ongoing research, the aim and goal of the discussions here is the elucidation of information on molecular structure and dynamics, the environment of the sample molecules and their state of association, interactions with solvent, and many other topics.

Molecular (or atomic) spectroscopy is usually classified by the wavelength ranges (or energies) of the electromagnetic radiation (e.g., microwave or infrared spectroscopies) interacting with the molecular systems. These spectral ranges are summarized in Table I.1.

Table I.1 Table of photon energies and spectroscopic ranges

| νphoton | λphoton | Ephoton (J) | Ephoton (kJ mol−1) | Ephoton (cm−1) | Transition |

| Radio | 750 MHz | 0.4 m | 5 × 10−25 | 3 × 10−4 | 0.025 | NMR |

| Microwave | 3 GHz | 10 cm | 2 × 10−24 | 0.001 | 0.1 | EPR |

| Microwave | 30 GHz | 1 cm | 2 × 10−23 | 0.012 | 1 | Rotational |

| Infrared | 3 × 1013 Hz | 10 µm | 2 × 10−20 | 12 | 1 000 | Vibrational |

| UV-visible | 1015 | 300 nm | 6 × 10−19 | 360 | 30 000 | Electronic |

| X-ray | 1018 | 0.3 nm | 6 × 10−16 | 3.6 × 105 | 3 × 107 | X-ray absorption |

In Table 1.1, NMR and EPR stand for nuclear magnetic and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, respectively. In both these spectroscopic techniques, the transition energy of a proton or electron spin depends on the applied magnetic field strength. All techniques listed in Table 1.1 can be described by absorption processes (see below) although other descriptions, such as bulk magnetization in NMR, are possible as well.

The interaction of the radiation with molecules or atoms that was referred to above as an “absorption process” requires that the energy difference between two (molecular or atomic) “stationary states” exactly matches the energy of the photon:

where h denotes Planck's constant (h = 6.6 × 10−34Js) and ν the frequency of the photon, in s−1. As seen from Table 1.1, these photon energies are between 10−16 and 10−25 J/molecule or about 10−4 to 105 kJ/(mol photons). In an absorption process, one photon interacts with one atom or molecule to promote it into a state of higher excitation, and the photon is annihilated. The reverse process also occurs where an atomic or molecular system undergoes a transition from a more highly excited to a less highly excited state; in this process, a photon is created. However, this view of the interaction between light and matter is somewhat restrictive, since radiation interacts with matter even if its wavelength is far different than the specific wavelength at which a transition occurs. Thus, a classification of spectroscopy, which is more general than that given by the wavelength range alone, would be a resonance/off-resonance distinction. Many of the effects described and discussed in spectroscopy books are observed as resonance interactions where the incident light, indeed, possesses the exact energy of the molecular transition in question. IR and UV/vis absorption spectroscopy, microwave spectroscopy, or EPR are examples of such resonance interactions. However, interaction of light and matter occurs, in a more subtle way, even if the wavelength of light is different from that of a molecular transition. These off-resonance interactions between electromagnetic radiation and matter give rise to well-known phenomena such as the refractive index of dielectric materials, and the anomalous dispersion of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.6.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Chemie ► Analytische Chemie |

| Technik ► Maschinenbau | |

| Technik ► Umwelttechnik / Biotechnologie | |

| Schlagworte | Bildgebende Verfahren i. d. Biomedizin • biomedical engineering • Biomedical Imaging • Biomedizintechnik • Biophysical and bio-structural research • Chemie • Chemistry • computational methods • Diagnostic Applications • infrared spectroscopy • materials characterization • Materials Science • Materialwissenschaften • microscopic data acquisition • Micro-spectral datasets • Micro-Spectroscopy • multivariate analysis • Raman spectroscopy • Resonance and Non-linear Raman effects • Small and large molecules • Spectral Cytopathology (SCP) • Spectral Histopathology (SHP) • spectroscopy • Spektroskopie • Time Resolved Spectroscopy • Vibrational optical activity • vibrational spectroscopy • Werkstoffprüfung • Werkstoffprüfung |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-82498-9 / 1118824989 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-82498-6 / 9781118824986 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich