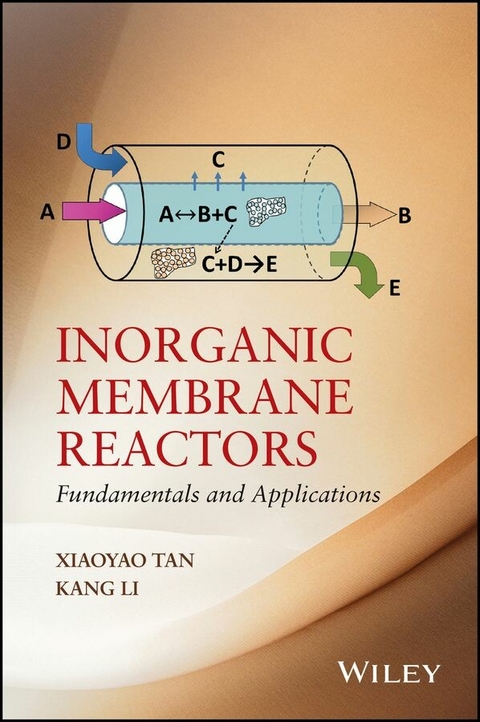

Inorganic Membrane Reactors (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-67255-6 (ISBN)

Membrane reactors combine membrane functions such as separation, reactant distribution, and catalyst support with chemical reactions in a single unit. The benefits of this approach include enhanced conversion, increased yield, and selectivity, as well as a more compact and cost-effect design of reactor system. Hence, membrane reactors are an effective route toward chemical process intensification.

This book covers all types of porous membrane reactors, including ceramic, silica, carbon, zeolite, and dense metallic reactors such as Pd or Pd-alloy, oxygen ion-conducting, and proton-conducting ceramics. For each type of membrane reactor, the membrane transport principles, membrane fabrication, configuration and operation of membrane reactors, and their current and potential applications are described comprehensively. A summary of the critical issues and hurdles for each membrane reaction process is also provided, with the aim of encouraging successful commercial applications.

The audience for Inorganic Membrane Reactors includes advanced students, industrial and academic researchers, and engineers with an interest in membrane reactors.

Membrane reactors combine membrane functions such as separation, reactant distribution, and catalyst support with chemical reactions in a single unit. The benefits of this approach include enhanced conversion, increased yield, and selectivity, as well as a more compact and cost-effect design of reactor system. Hence, membrane reactors are an effective route toward chemical process intensification. This book covers all types of porous membrane reactors, including ceramic, silica, carbon, zeolite, and dense metallic reactors such as Pd or Pd-alloy, oxygen ion-conducting, and proton-conducting ceramics. For each type of membrane reactor, the membrane transport principles, membrane fabrication, configuration and operation of membrane reactors, and their current and potential applications are described comprehensively. A summary of the critical issues and hurdles for each membrane reaction process is also provided, with the aim of encouraging successful commercial applications. The audience for Inorganic Membrane Reactors includes advanced students, industrial and academic researchers, and engineers with an interest in membrane reactors.

Xiaoyao Tan is Professor of Chemical Engineering at Tianjin Polytechnic University, China Currently he teaches Membrane Science and Technology to undergraduate students. He received his PhD from Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1995, and has been working in the membrane area for more than 15 years. His research interests involve the preparation and characterization of various inorganic membranes such as ceramics, metals, and zeolites for fluid separations/reactions. He has published 120+ research papers in international referred journals, 15 patents and 4 book chapters in the area of inorganic membranes and membrane reactors. Kang Li is Professor of Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London. His present research interests are in the preparation and characterisation of polymeric and inorganic hollow fibre membranes, fluid separations using membranes, and membrane reactors for energy application and CO2 capture. Kang Li currently leads a research group at Imperial of 2 MSc students, 8 PhD students and 3 post-doctorial research fellows. He has published over 180 research papers in international referred journals, holds five patents, and is the author of a book in the area of ceramic membranes (Ceramic Membranes for Separation and Reaction, John Wiley, 2007).

1

Fundamentals of Membrane Reactors

1.1 Introduction

A membrane reactor (MR) is a device integrating a membrane with a reactor in which the membrane serves as a product separator, a reactant distributor, or a catalyst support. The combination of chemical reactions with the membrane functions in a single step exhibits many advantages, such as preferentially removing an intermediate (or final) product, controlling the addition of a reactant, controlling the way for gases to contact catalysts, and combining different reactions in the same system. As a result, the conversion and yield can be improved (even beyond the equilibrium values), the reaction conditions can be alleviated, and the capital and operational costs can be reduced significantly. Different reactions usually require different types of membranes. Membrane reactors are also operated in different modes. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce readers to the main concepts of membranes and membrane reactors. The principles, structure, and operation of inorganic membrane reactors are presented below.

1.2 Membrane and Membrane Separation

A membrane is defined as a region of discontinuity interposed between two phases [1]. It restricts the transport of certain chemical species in a specific manner. In most cases, the membrane is a permeable or semi-permeable medium and is characterized by permeation and perm-selectivity. In other words, the membrane may have the ability to transport one component more readily than others due to the differences in physical and/or chemical properties between the membrane and the permeating components.

1.2.1 Membrane Structure

Membranes can be classified according to different viewpoints – for example, membrane materials, morphology and structure of the membranes, preparation methods, separation principles, or application areas. In general, the most illustrative means of classifying membranes is by their morphology or structure, because the membrane structure determines the separation mechanism and the membrane application. Accordingly, two types of membranes may be distinguished: symmetric and asymmetric membranes. Symmetric membranes have a uniform structure in all directions, which may be either porous or non-porous (dense). A special form of symmetric membrane is the liquid immobilized membrane (LIM) that consists of a porous support filled with a semi-permeable liquid or a molten salt solution. Asymmetric membranes are characterized by a non-uniform structure comprising a selective top layer supported by a porous substrate of the same material. If the selective layer is made of a different material from the porous substrate, we have a composite membrane. Figure 1.1 shows schematically the principal types of membranes.

Figure 1.1 Schematic diagrams of the principal types of membranes: (a) porous symmetric membrane; (b) non-porous/dense symmetric membrane; (c) liquid immobilized membrane; (d) asymmetric membrane with porous separation layer; (e) asymmetric membrane with dense separation layer.

Sometimes, the porous support itself may also possess different pores and exhibit an asymmetric structure. Figure 1.2 depicts the cross-section of an asymmetric membrane where the structural asymmetry is clearly observed [2]. The asymmetric membranes usually have a thin selective top layer to obtain high permeation flux and a thick porous support to provide high mechanical strength. The resistance of the membrane to mass transfer is largely determined by the thin top layer.

Figure 1.2 Cross-sectional SEM image of an asymmetric membrane.

Reproduced from [2]. With permission from Elsevier.

Based on the membrane structure and separation principle, membranes can also be classified into porous and dense (non-porous) membranes, as depicted schematically in Figure 1.3. The porous membranes have a porous separation layer and induce separation by discriminating between particle (molecular) sizes (Figure 1.3(a)). The separation characteristics (i.e., flux and selectivity) are determined by the dimensions of the pores in the separation layer. The membrane material is of crucial importance for chemical, thermal, and mechanical stability but not for flux and rejection. The non-porous/dense membranes have a dense separation layer, and separation is achieved through differences in solubility or reactivity and the mobility of various species in the membrane. Therefore, the intrinsic properties of the membrane material determine the extent of selectivity and permeability. The LIMs can be considered as a special dense membrane since separation takes place via the filled liquid semi-permeable phase, although a porous structure is contained within the membrane.

Figure 1.3 Schematic drawing of the permeation in porous and dense membranes.

1.2.2 Membrane Separation

The membrane separation process is characterized by the use of a membrane to accomplish a particular separation. Figure 1.4 shows the concept of a membrane separation process. By controlling the relative transport rates of various species, the membrane separates the feed into two streams: the retentate and the permeate. Either the retentate or the permeate can be the product of the separation process.

Figure 1.4 Schematic drawing of the membrane separation process.

The performance of a membrane in separation can be described in terms of permeation rate or permeation flux (mol m–2 s–1) and perm-selectivity. The permeation flux is usually normalized per unit of pressure (mol m–2 s–1 Pa–1), called the permeance, or is further normalized per unit of thickness (mol m m–2 s–1 Pa–1), called the permeability, if the thickness of the separation layer is known. In many cases only a part of the separation layer is active, and the use of permeability gives rise to larger values than the real intrinsic ones. Therefore, in case of doubt, the flux values should always be given together with the (partial) pressure of the relevant components at the high-pressure (feed) and low-pressure (permeate) sides of the membrane as well as the apparent membrane thickness.

The permeation flux is defined as the molar (or volumetric or mass) flow rate of the fluid permeating through the membrane per unit membrane area. It is determined by the driving force acting on an individual component and the mechanism by which the component is transported. In general cases, the permeation flux (J) through a membrane is proportional to the driving force; that is, the flux–force relationship can be described by a linear phenomenological equation:

where L is called the phenomenological coefficient and dX/dx is the driving force, expressed as the gradient of X (temperature, concentration, pressure, etc.) along the coordinate (x) perpendicular to the transport barrier. The mass transport through a membrane may be caused by convection or by diffusion of an individual molecule – induced by a concentration, pressure, or temperature gradient – or by an electric field. The driving force for membrane permeation may be the chemical potential gradient (Δμ) or the electrical potential gradient (Δϕ) or both (the electrochemical potential is the sum of the chemical potential and the electrical potential). In case the concentration gradient serves as the driving force, the transport equation can be described by Fick's law:

where DAm (m2 s–1) is the diffusion coefficient of component A within the membrane. It is a measure of the mobility of the individual molecules in the membrane and its value depends on the properties of the species, the chemical compatibility of the species, the membrane material, and the membrane structure as well. In practical diffusion-controlled separation processes, useful fluxes across the membrane are achieved by making the membranes very thin and creating large concentration gradients across the membrane.

For the pressure-driven convective flow, which is most commonly used to describe flow in a capillary or porous medium, the transport equation may be described by Darcy's law:

where dp/dx is the pressure gradient existing in the porous medium, cA is the concentration of component A in the medium, and K is a coefficient reflecting the nature of the medium. In general, convective-pressure-driven membrane fluxes are high compared with those obtained by simple diffusion. More details of the transport mechanisms in membranes can be found elsewhere [3].

The perm-selectivity of a membrane toward a mixture is generally expressed by one of two parameters: the separation factor and retention. The separation factor is defined by

where yA and yB, xA and xB are the mole fractions of components A and B in the permeate and the retentate streams, respectively.

The retention is defined as the fraction of solute in the feed retained by the membrane, which is expressed...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.3.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Chemie ► Technische Chemie |

| Technik ► Umwelttechnik / Biotechnologie | |

| Schlagworte | Approach • Benefits • Book • Chemical • chemical engineering • Chemische Verfahrenstechnik • Conversion • costeffect design • effective route • Electrical & Electronics Engineering • Electronic materials • Elektronische Materialien • Elektrotechnik u. Elektronik • Functions • intensification • Materials Science • Materialwissenschaften • Membrane • Membrane Reactors • Metallic • Pd • Porous • Process • Reactions • Reactor • Reactors • Single • System • Types • Unit |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-67255-0 / 1118672550 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-67255-6 / 9781118672556 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich