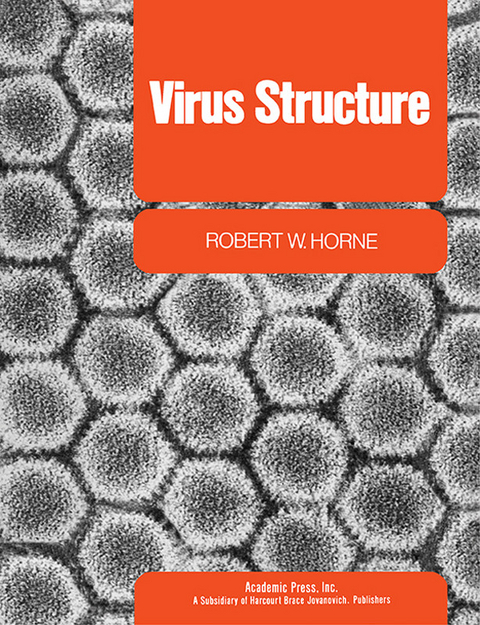

Virus Structure (eBook)

56 Seiten

Elsevier Science (Verlag)

978-1-4832-7392-1 (ISBN)

Virus Structure describes the physical characteristics of isolated viruses that represent typical structural groups, with particular reference to those features analyzed with the aid of the electron microscope. For descriptive purposes, the book has been divided into sections starting with the small icosahedral viruses and leading to the larger and more sophisticated structures, regardless of whether they are animal, plant, or bacterial viruses. These include double-stranded DNA icosahedral viruses, herpesvirus, viruses with helical symmetry, and viruses with complex or a combination of symmetries. Many common architectural features will be found in those viruses selected for discussion in each of the sections, and for these reasons the introduction places some emphasis on the symmetry elements rather than the shapes of viruses. The mechanism by which viruses enter host cells and the events that follow once the cell has been infected are only mentioned briefly as the virus-host interaction is a relatively complex one.

Front Cover 1

Virus Structure 2

Copyright Page 3

Table of Contents 4

PREFACE 5

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 5

INTRODUCTION 6

SYMMETRY IN VIRIONS 8

SMALL DNA ICOSAHEDRAL VIRUSES 17

SMALL RNA ICOSAHEDRAL VIRUSES (NAPOVIRUSES AND PICORNAVIRUSES) 17

DOUBLE-STRANDED DNA ICOSAHEDRAL VIRUSES 21

HERPESVIRUS 25

VIRUSES WITH HELICAL SYMMETRY 27

VIRUSES WITH COMPLEX OR A COMBINATION OF SYMMETRIES 37

SUMMARY 50

REFERENCES 52

INDEX 56

SYMMETRY IN VIRIONS

Publisher Summary

From the studies on isolated virus particles and their components carried out with the aid of a large variety of physicochemical methods, it is now possible to group these infective agents within three main geometrical and symmetry plans. This chapter discusses the composition of geometrical groups: (1) virions with helical symmetry, (2) those with icosahedral symmetry, and (3) those with combined symmetries or complex geometrical patterns. The rod-shaped tobacco mosaic virus is the best example for illustrating the presence of helical symmetry in a virion. The chapter presents the morphology of the rods as seen in the electron microscope together with the data derived from X-ray diffraction studies. The symmetry and shape of the regular icosahedron is also presented in the chapter. It is shown that the icosahedron possesses 5. 3. 2. rotation symmetry which is particularly relevant to the viral capsids.

There is an increasing amount of evidence from various experimental approaches to show that many components in living cells are probably put together by self-assembly. One of the clear examples is that of small viruses in which the amount of nucleic acid contained in the particles is limited and is only capable of coding for a small number of proteins. This point was discussed by Crick and Watson (18) who considered that protein molecules as asymmetric units are most likely assembled according to a geometrical or symmetrical plan.

From the studies on isolated virus particles and their components carried out with the aid of a large variety of physicochemical methods, it is now possible to group these infective agents within three main geometrical and symmetry plans. The geometrical groups comprise (a) virions with helical symmetry, (b) those with icosahedral symmetry, and (c) those with combined symmetries or complex geometrical patterns (see 14, 15, 40).

Helical Symmetry

The rod-shaped tobacco mosaic virus is the best example for illustrating the presence of helical symmetry in a virion. From X-ray diffraction studies complemented by biochemical analysis and electron microscopy, it has been possible to build a three-dimensional model of the TMV structure. The morphology of the rods as seen in the electron microscope together with the data derived from X-ray diffraction studies is illustrated in Figs. 2 and 17. The ribonucleic acid is deeply embedded in the protein, and the former is arranged in a helical array. The protein is composed of identical structure or chemical asymmetric units arranged in a regular helix. The pitch of the helix is 2.3 nm and the number of structure units in each turn of the helix is approximately 13. It follows that in every 3 turns of the helix there will be an axial repeat in the structure of about 6.9 nm containing 49 structure units. It should be noted that each structure unit possesses 6 neighbors (apart from those located at the ends of the rods), and the units are related to each other in precisely the same way. The bond sites between neighboring structure units would result in the rigid rods illustrated in the electron micrograph shown in Fig. 17 possessing a strict helix.

It follows that more flexuous helical structures could result from there being preferential specific bonding sites between structure units in one direction to assemble a structure resembling a spring. That is to say, there would be few bond interactions between neighboring turns of the helix. This type of quasi-helix can be seen in the components forming the nucleoprotein in citrus tristeza virus, potato virus X, and the myxoviruses as illustrated in Figs. 18 and 21. A large number of rodlike and filamentous structures are assembled according to a helical or quasi-helical pattern (15).

Icosahedral Symmetry

Examination of a large range of different “spherical-shaped” viruses with the aid of X-ray diffraction techniques and high resolution electron microscopy has established that the capsids of these particles are built according to icosahedral symmetry. For the reasons mentioned earlier concerning the economic packing of protein molecules to enclose space, there are also the problems of how such a structure assembles itself within the infected cell and the formation of a structure possessing minimum stress.

The icosahedron is one of the five Platonic bodies (see Fig. 4), and in order to discuss some of the electron micrographs of icosahedral viruses, some brief details of the geometrical properties of the icosahedra are needed. The five Platonic bodies consist of the tetrahedron, octahedron, cube, icosahedron, and dodecahedron. These five bodies can be inscribed within a sphere in such a way that their vertexes are equidistant apart at the surface of a sphere. They are also related to Euler’s formula S + 2 = V + F, where S = the number of sides, V = number of vertexes, and F = number of faces.

Fig. 4 The five Platonic bodies: (A) tetrahedron, (B) octahedron, (C) cube, (D) dodecahedron, and (E) icosahedron.

The symmetry and shape of the regular icosahedron is illustrated in Fig. 5, and it is important to mention that the symmetry operation is rotational. It will be seen from the diagram that the icosahedron possesses 5. 3. 2. rotation symmetry which is particularly relevant to the viral capsids discussed later.

Fig. 5 The icosahedron viewed in three positions: (A) looking along an axis of fivefold rotational symmetry (apex); (B) an axis of threefold rotational symmetry (face); and (C) an axis of twofold rotational symmetry (edge).

The important point to be made here is that it is possible to pack asymmetric units or structure units in such a way that they will form an icosahedral shell. One simple example is illustrated in Fig. 7 which shows how the packing of identical units (the lines forming the edges of the hexamers and pentamers) in accordance with icosahedral symmetry generates a number of pentamer and hexamer patterns. A similar series of patterns can result by drawing the great circle radius of a sphere to intersect points of icosahedral symmetry (Fig. 8). These latter patterns fall within the subject of descriptive geometry and are considered as geodesies or multisymmetric polyhedra. They are of greater interest to the mathematician than the virologist (27).

Fig. 7 A spherical object constructed of pentamers and hexamers arranged according to 5. 3. 2. (icosahedral) rotational symmetry. When viewed in the position (A) the object is seen along a fivefold rotational axis. At (B) the object is viewed along a threefold rotational axis; at (C), along a twofold symmetry axis. The identical units are the lines forming the edges of the hexamers and pentamers.

Fig. 8 The sphere illustrated in the diagram shows the generation of pentamer, hexamer, and spherical triangles resulting from drawing the great circle radius to intersect points of icosahedral symmetry. A regular icosahedron (Fig. 5) could be placed in the sphere in such a way that the 12 apexes would be located at the center of the 12 pentamers indicated by the black spots at the sphere surface.

It is possible to construct a number of crystallographic models including icosahedra projected on plane surfaces. Regular patterns corresponding to the model are drawn on a suitable surface to form “nets” or appropriate facets. The nets can be folded or plaited in such a way that they result in the three-dimensional polyhedron. For those readers interested in the construction of the polyhedra related to viruses, the publications of Cundy and Rollett (19) and Pargeter (69) are particularly relevant.

For the purposes of understanding and analyzing virus capsids and their components we shall refer to Figs. 9 and 10, which cover the essential geometrical arrangements relating to the symmetry and icosahedra. It is also possible to construct a series of simple models consisting of 12 pentamer units (penton capsomeres) and an x number of hexamer units (hexon capsomeres) in accordance with icosahedral symmetry which represent the capsids observed in various “spherical” viruses. The model shown in Fig. 9D shows a capsid consisting of 12 morphological units as pentamers located on the 12 fivefold rotational symmetry axes of an icosahedron. This model represents the most basic and smallest capsid. Particles of this type have been observed in the electron microscope and the reader is referred to the details of bacteriophage ϕX174 described under small DNA viruses (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9 The icosahedral models have been constructed from hollow pentamer and hexamer columnar prisms to represent possible virus capsids. These prisms indicate the morphological units or capsomeres resolved in negatively stained preparations when photographed in the electron microscope. At (A) the model consists of 162 capsomers with the fivefold units indicated at the surface. The model shown at (B) is constructed of 92 capsomeres. It can be seen that, by reducing the number of hexamers from 3 as in (A) to 2 between the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.6.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Biochemie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Evolution | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Angewandte Physik | |

| Technik | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4832-7392-X / 148327392X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4832-7392-1 / 9781483273921 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich