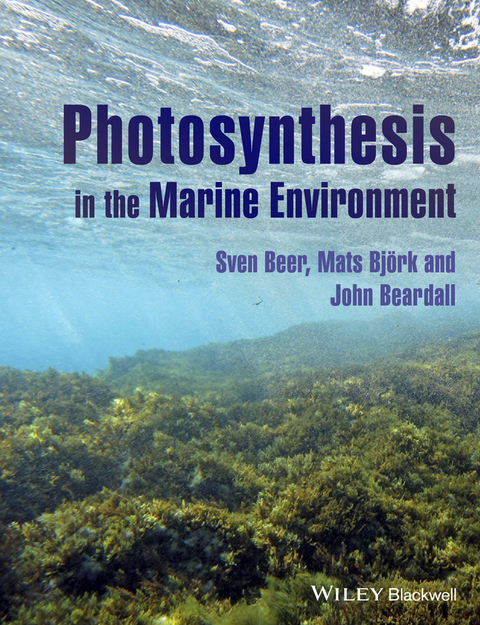

Photosynthesis in the Marine Environment (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-80338-7 (ISBN)

'Marine photosynthesis provides for at least half of the primary production worldwide...'

Photosynthesis in the Marine Environment constitutes a comprehensive explanation of photosynthetic processes as related to the special environment in which marine plants live. The first part of the book introduces the different photosynthesising organisms of the various marine habitats: the phytoplankton (both cyanobacteria and eukaryotes) in open waters, and macroalgae, marine angiosperms and photosymbiont-containing invertebrates in those benthic environments where there is enough light for photosynthesis to support growth, and describes how these organisms evolved. The special properties of seawater for sustaining primary production are then considered, and the two main differences between terrestrial and marine environments in supporting photosynthesis and plant growth are examined, namely irradiance and inorganic carbon. The second part of the book outlines the general mechanisms of photosynthesis, and then points towards the differences in light-capturing and carbon acquisition between terrestrial and marine plants. This is followed by discussing the need for a CO2 concentrating mechanism in most of the latter, and a description of how such mechanisms function in different marine plants. Part three deals with the various ways in which photosynthesis can be measured for marine plants, with an emphasis on novel in situ measurements, including discussions of the extent to which such measurements can serve as a proxy for plant growth and productivity. The final chapters of the book are devoted to ecological aspects of marine plant photosynthesis and growth, including predictions for the future."e;Marine photosynthesis provides for at least half of the primary production worldwide..."e; Photosynthesis in the Marine Environment constitutes a comprehensive explanation of photosynthetic processes as related to the special environment in which marine plants live. The first part of the book introduces the different photosynthesising organisms of the various marine habitats: the phytoplankton (both cyanobacteria and eukaryotes) in open waters, and macroalgae, marine angiosperms and photosymbiont-containing invertebrates in those benthic environments where there is enough light for photosynthesis to support growth, and describes how these organisms evolved. The special properties of seawater for sustaining primary production are then considered, and the two main differences between terrestrial and marine environments in supporting photosynthesis and plant growth are examined, namely irradiance and inorganic carbon. The second part of the book outlines the general mechanisms of photosynthesis, and then points towards the differences in light-capturing and carbon acquisition between terrestrial and marine plants. This is followed by discussing the need for a CO2 concentrating mechanism in most of the latter, and a description of how such mechanisms function in different marine plants. Part three deals with the various ways in which photosynthesis can be measured for marine plants, with an emphasis on novel in situ measurements, including discussions of the extent to which such measurements can serve as a proxy for plant growth and productivity. The final chapters of the book are devoted to ecological aspects of marine plant photosynthesis and growth, including predictions for the future.

Sven Beer, Professor of Marine Botany, Tel Aviv University, Department of Plant Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. Mats Björk, Botany Department, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden. John Beardall, School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Australia.

About the authors ix

Preface xi

About the companion website xiii

Part I Plants and the Oceans 1

Introduction 1

Chapter 1 The evolution of photosynthetic organisms in the oceans 5

Chapter 2 The different groups of marine plants 15

2.1 Cyanobacteria 16

2.2 Eukaryotic microalgae 17

2.3 Photosymbionts 23

2.4 Macroalgae 27

2.5 Seagrasses 34

Chapter 3 Seawater as a medium for photosynthesis and plant growth 39

3.1 Light 40

3.2 Inorganic carbon 45

3.3 Other abiotic factors 52

Summary notes of Part I 55

Part II Mechanisms of Photosynthesis, and Carbon Acquisition in Marine Plants 57

Introduction to Part II 57

Chapter 4 Harvesting of light in marine plants: The photosynthetic pigments 61

4.1 Chlorophylls 61

4.2 Carotenoids 63

4.3 Phycobilins 64

Chapter 5 Light reactions 67

5.1 Photochemistry: excitation, de-excitation, energy transfer and primary electron transfer 67

5.2 Electron transport 74

5.3 ATP formation 76

5.4 Alternative pathways of electron flow 77

Chapter 6 Photosynthetic CO2-fixation and -reduction 81

6.1 The Calvin cycle 81

6.2 CO2-concentrating mechanisms 89

Chapter 7 Acquisition of carbon in marine plants 95

7.1 Cyanobacteria and microalgae 96

7.2 Photosymbionts 101

7.3 Macroalgae 104

7.4 Seagrasses 118

7.5 Calcification and photosynthesis 122

Summary notes of Part II 124

Part III Quantitative Measurements, and Ecological Aspects, of Marine Photosynthesis 127

Introduction to Part III 127

Chapter 8 Quantitative measurements 129

8.1 Gas exchange 131

8.2 How to measure gas exchange 133

8.3 Pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometry 137

8.4 How to measure PAM fluorescence 142

8.5 What method to use: Strengths and limitations 146

Chapter 9 Photosynthetic responses, acclimations and adaptations to light 157

9.1 Responses of high- and low-light plants to irradiance 157

9.2 Light responses of cyanobacteria and microalgae 163

9.3 Light effects on photosymbionts 164

9.4 Adaptations of carbon acquisition mechanisms to light 169

9.5 Acclimations of seagrasses to high and low irradiances 169

Chapter 10 Photosynthetic acclimations and adaptations to stress in the intertidal 175

10.1 Adaptations of macrophytes to desiccation 175

10.2 Other stresses in the intertidal 181

Chapter 11 How some marine plants modify the environment for other organisms 183

11.1 Epiphytes and other 'thieves' 183

11.2 Ulva can generate its own empires 185

11.3 Seagrasses can alter environments for macroalgae and vice versa 187

11.4 Cyanobacteria and eukaryotic microalgae 189

Chapter 12 Future perspectives on marine photosynthesis 191

12.1 'Harvesting' marine plant photosynthesis 191

12.2 Predictions for the future 192

12.3 Scaling of photosynthesis towards community and ecosystem production 194

Summary notes of Part III 197

References 199

Index 203

Part I

Plants and the Oceans

Introduction

Our planet as viewed from space is largely blue. This is because it is largely covered by water, mainly in the form of oceans (and we explain why the oceans are blue in Box 3.2, i.e. Box 2 in Chapter 3). So why then call this planet Earth? In our view, Planet Ocean, or Oceanus, would be a more suitable name; since the primary hit on Google for ‘Planet Ocean’ is a watch brand, let's meanwhile stick with Oceanus. Not only is the area covered by oceans larger than that covered by earth, rocks, cities and other dry places, but the volume of the oceans that can sustain life is vastly larger than that of their terrestrial counterparts. Thus, if we approximate that the majority of terrestrial life extends from just beneath the soil surface (where bacteria and some worms live) to some tens of metres (m) up (where the birds soar), and given the fact that, on the other hand, life in the oceans extends to their deepest depths of some 11 000 m, then a simple multiplication of the surface areas (∼70% for oceans and ∼30% for land) with the average depth of the oceans (3800 m), or height of terrestrial environments, gives the result that the oceans constitute a life-sustaining volume that is some 1000 times larger than that of the land. If we do the same calculation for plants only under the assumptions that the average terrestrial-plant height is 1 m (including the roots) and that there is enough light to drive diel positive apparent (or net) photosynthesis1 down to an average depth of 100 m, then the ‘life volume’ for plant growth in the oceans is 250 times that provided by the terrestrial environments.

It has been estimated that photosynthesis by aquatic plants2 provides roughly half of the global primary production3 of organic matter (see, e.g. the book Aquatic Photosynthesis by Paul Falkowski and John Raven). Given that the salty seas occupy much larger areas of our planet than the freshwater lakes and rivers, there is no doubt that the vastly greater part of that aquatic productivity stems from photosynthetic organisms of the oceans. Other researchers have indicated that the marine primary (i.e. photosynthetic) productivity may be even higher than the terrestrial one: Woodward in a 2007 paper estimated the global marine primary production to be 65 Gt4 carbon year−1 while the terrestrial one was 60 Gt year−1. This, and recently increasing realisations of the important contributions from very small, cyanobacterial, organisms previously missed by researchers (see Figure I.1a), lends thought to the realistic possibility that photosynthesis in the marine environment contributes to the major part of the primary productivity worldwide. Some of the players contributing to the marine primary production are depicted in Fig. I.1, while many others are described in Chapter 2.

Figure I.1 Some of the ‘players’ in marine photosynthetic productivity. (a) The tiniest cyanobacterium (Prochlorococcus marinus) – the cyanobacteria may provide close to half of the oceanic primary production, at least in nutrient-poor waters. (b) A eukaryotic phytoplankter (the microalga Chaetoceros sp.) – the microalgae are probably the main primary producers of the seas. (c) Two photosymbiont- (zooxanthellae-)containing corals from the Red Sea (Millepora sp., left, and Stylophora pistillata, right) – while quantitatively minor providers to global primary production, these photosymbionts keep the coral reefs alive. (d) The temperate macroalga Laminaria digitata – macroalgae provide maybe up to 10% of the marine primary production. (e) A meadow of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica – even though their primary productivity is amongst the highest in the world on an area basis, the contribution of seagrasses to the global primary production is small (but they form beautiful meadows!). Photos with permission from, and thanks to, William K. W. Li (Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, NS, Canada) and Frédéric Partensky (Station Biologique, CNRS, Roscoff, France) (a), Olivia Sackett (b), Sven Beer (c), Katrin Österlund (d) and Mats Björk (e).

Because marine plants are the basis for generating energy for virtually every marine food web5, and given that the oceans may be even more productive than all terrestrial environments together, it is logical that the process of marine photosynthesis should be of interest to every biologist. But what about non-biologists? Why should the average person care about marine photosynthesis or marine plants? One of SB's in-laws has never eaten algae or any other products stemming from the sea; he hates even the smell of fish! However, after telling him that the oxygen (O2) we breathe is (virtually, see Box 1.2) exclusively generated by plants through the process of photosynthesis, and that approximately half of the global photosynthetic activity takes place in the seas, even he agreed that any interference with the oceans that would lower their photosynthetic production would indeed also jeopardise his own wellbeing. And for those who like fish as part of their diet, the primary production of phytoplankton6 is directly related to global fisheries' catches. So, for whatever reason, the need to maintain a healthy marine environment that promotes high rates of photosynthesis and, accordingly, plant growth in the oceans should be of high concern for everyone, just as it is of more intuitive concern to maintain healthy terrestrial environments.

This book will in this, its first, part initially review what we think we know about the evolution of marine photosynthetic organisms. Then, the different photosynthetic ‘players’ in the various marine environments will be introduced: the cyanobacteria and microalgae that constitute the bulk of the phytoplankton in sunlit open waters, the photosymbionts that inhabit many marine invertebrates, and the different macroalgae as well as seagrasses in those benthic7 environments where there is enough light during the day for dielly positive net (or ‘apparent’, see, e.g. Section 8.1) photosynthesis to take place. Finally, the third chapter of this part will outline the different properties of seawater that are conducive to plant photosynthesis and growth, and in doing so will especially focus on what we view as the two main differences between the marine and terrestrial environments: the availability of light and inorganic carbon8. In doing so, this first part will, hopefully, become the basis for understanding the other two parts, which deal more specifically with photosynthesis in the marine environment.

Personal Note: Why algae are important

Most of the students taking my (JB) Marine Biology class are more interested in the animals (especially the ‘charismatic’ mega-fauna like dolphins, turtles and whales) than in those plants that ultimately provide their food. Indeed, when I first started my PhD, my supervisor advised me to “…never admit at parties to what you are studying (i.e. algae), or no-one will talk to you…”. However, algae (as a major proportion of the marine flora) are far more important than ‘just those things that cause green scum in swimming pools’. I deal with this in the very first lecture of my course by asking the students to put down their pens (or these days their laptops) and take a deep breath. They do this and I then I ask them to take a second deep breath – by this time they are wondering if I've finally lost it, but then I explain that the second breath they have just taken is using oxygen from photosynthesis by marine plants and that if it wasn't for this group of organisms, not only would our fisheries be more depleted than they already are, but also we'd only have half the oxygen to breath! This tends to focus their attention on those organisms at the bottom of the marine food chain and the fact that algae are responsible for around half of the biological CO2 draw-down that occurs on our planet. As a consequence, algae get more of their respect.

Notes

1 Diel (= within 24 h, i.e. during the day AND the night) apparent (or net) photosynthesis is the metabolic gas exchange of CO2 or O2 resulting from photosynthesis and respiration in a 24-h cycle of light (where both processes take place) and darkness (where only respiration occurs). Net photosynthesis is positive if, during these 24 h, there is a net consumption of CO2 or a net production of O2. 2The word ‘plant(s)’ is used here in the wider sense of encompassing all photosynthetic organisms, including those algae sometimes classified as belonging to the kingdom Protista (in, e.g. Peter Raven's et al. textbook Biology of Plants) and, unconventionally, also those photosynthetic prokaryotes referred to as cyanobacteria. The latter are of course not included taxonomically in the kingdom Plantae (they belong to the Eubacteria), but can, just like the algae, functionally be considered as ‘plants’ in terms of their (important) role as primary (photosynthetic) producers in the oceans. 3Since photosynthesis is the basic process that produces energy for the life and growth of all organisms, its outcome is often called primary production; the rate at...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.3.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Biochemie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Limnologie / Meeresbiologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Ãkologie / Salzwasser • Basis • Biowissenschaften • Book • Botanik • Botanik / Biochemie • Comprehensive • Environment • Explanation • First • Half • least • Life Sciences • Marine • Marine Ecology • Meeresbiologie • Nearly • Ökologie / Salzwasser • Organisms • Part • Photosynthese • photosynthesis • photosynthesising • Photosynthetic • Planets • plant biochemistry • plant science • processes • Production • provides • Reader • relate • Special |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-80338-8 / 1118803388 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-80338-7 / 9781118803387 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich