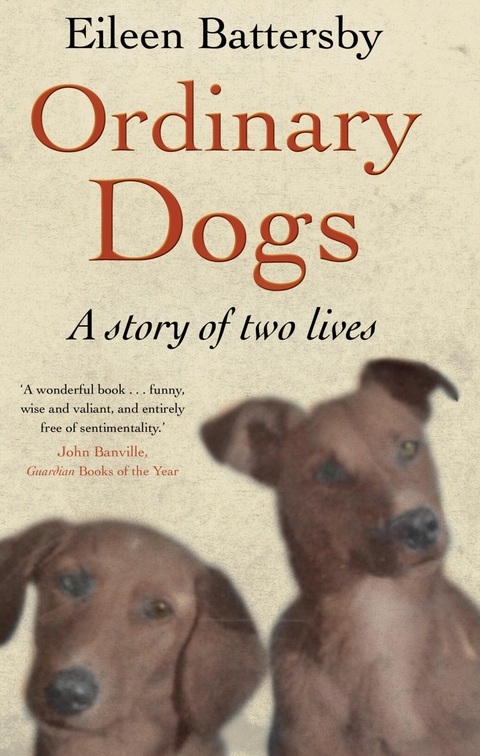

Ordinary Dogs (eBook)

336 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-27785-8 (ISBN)

Born in California, Eileen Battersby is an Irish Times staff arts journalist and the paper's Literary Correspondent. Four-time winner of the National Arts Journalist of the Year award, she lives in the country with her daughter, Nadia, and their horses, dogs and cats. Her ambition is to breed and/or produce an Olympic showjumper.

Eileen Battersby is the chief literature critic of The Irish Times and is, in the words of John Banville, 'the finest fiction critic we have'. But her first full-length book is not about international literature or the state of the novel. It is about dogs. Two dogs in particular, with the unlikely names of Bilbo and Frodo. She adopted the first from a horrible dog pound, and the second decided he liked her and moved in to join the family. She was in her very early twenties, an intensely serious student and runner who had just moved to Ireland from California. The dogs became her most loyal companions for over twenty years, witnesses to an often difficult human life and more important to her than most other humans. This book is about two animals with personalities, emotions and prejudices. It is unlike any other book ever written about dogs. It is not sentimental or twee. Battersby became intimately involved in the lives of these intelligent, shrewd creatures, and brings them to life with rare passion and insight. She writes honestly and movingly about the reasons why, for certain people - especially women - there is more integrity in the mysterious relationship with a mammal who cannot speak than there is in most of the relationships that human society has to offer.

The only dogs I knew when I was small belonged to other people.

The first dog I became close to was an old yellow hound that lived in the mountain village near Lake Arrowhead in California, where we had a cabin. He was self-possessed and had long, flat ears and was lean, rangy and sinewy, respected by all. If I ever knew his name I have long since forgotten it. But he should have been called Colonel: he ambled about like a Southern gent, stiff in his quarters, and probably had his own views on how the Civil War had been fought and lost. I see him now in my mind’s eye, sauntering slowly, struggling for balance as he cocks a leg against a tree or a rock, or that intrusive automobile there, the one with the out-of-state plates, a car that had no right to be cluttering up the pine-forest path where the clearing extended beyond the tree line to the mountains.

He may have been born there, or perhaps he just fetched up one fine day and decided he liked the lake view and the sharp, clean mountain air. He would stretch out in the sun on the porch of his owner’s large clapboard house with the flaking blue paint and sigh at regular intervals. His calm eyes were the colour of pewter. There’s a photograph of a young child on his back; I like to think it’s me. With age the yellow of his coat faded to pale, dirty grey, his jaw became slacker and his teeth deserted him. Together we’d watched a skunk browsing through the undergrowth on a high bank veined by the roots of ancient trees, always making sure they were roots and not one of those swift-moving mountain snakes. He’d come counting squirrels with me and understood not to scare them. He must have known by heart long passages from The Incredible Journey, that classic story about two dogs and a Siamese cat who crossed Canada together to return home. I used to read it aloud to him.

One summer he wasn’t there any more. A first loss; but he was never my dog – a friend, but not my dog. I had had no rights over him. He had not been allowed to sleep by my bed in the attic room with the sharply pitched roof. I wasn’t even allowed to bring him into the kitchen downstairs. But at least I could mourn him, and I missed him. Even now, I often think of his flat-footed gait and his habit of leaning against me for support.

There were other dogs. The dogs on leashes in the park, the ones you could pet without the owners becoming tense; the dogs who raided picnics and upended beach baskets. I remember a skinny collie that once ran into a bakery while we all watched. The dog was frantic and intent as he tore an iced birthday cake apart, gulping down huge bits, choking and spitting in desperation. It happened in La Jolla, a trendy enclave beside San Diego, near the US–Mexico border. The baker’s wife, who was perhaps Austrian or possibly Swiss, shouted in German and threw an order book at the dog; her face was red, and the people who had ordered the cake for a party later that day gazed mutely at the debris and shrugged the way naturally resigned people do.

Years passed, and I always liked dogs, worrying about the fate of hungry strays, but never having a dog of my own, always having to decline the offer of puppies. I was the product of an ultra-clean home and was neurotically tidy, the sort of kid who wouldn’t sleep on pillows in case I creased them. I used to vacuum my bedroom before I went to school. My books and music were filed according to subject as if in a library.

Somehow the timing was never right. But then one day it was. I was no longer living in a rented room, or staying in someone else’s house. I had just completed writing a thesis about Thomas Wolfe, a restless, troubled individual from Asheville, North Carolina. When he moved to New York to become a writer, he often wandered the streets at night, arguing with himself. I reckoned that my life would be very different from his – and far quieter. I had a cottage, small and bare except for books, so many books. Sheets of brown paper covered most of the windows. There was no heating and the cottage was isolated, but it was my first house. Then strange things started happening during the night. Laundry was stolen off the line and a tracksuit top was found lying on the doorstep in the morning, folded neatly but cut in two. Clay pots would be smashed, the plants trampled. My bike was stolen, as was its replacement. I needed a dog.

One bright winter morning in early December, a Tuesday, I set off to get a dog. I wanted a big German Shepherd; I would call him Ludwig in honour of Beethoven and take him for runs. My friend Sophie’s mother, Trudi, was going to drive me to the dogs’ home. She had told me that it was all very well buying a dog from a breeder but, if I went to a pound, I would be saving a dog’s life. Such a dog would have superior intelligence, a stronger character and an intuitive understanding of the most important things.

On the drive there I felt a surge of happiness. I didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission; this would be my dog.

At the pound, the first thing I noticed was the noise: the barking, the howling, the communal despair and, above all, the smells. There was the harsh, medicinal aroma, intended to mask the animal odours. Buckets of undiluted disinfectant must have been poured neat on to the ground and into the cages, under all that newspaper. But the strongest, most penetrating scent that asserted itself was cat pee. The animals endured that in confined spaces, inhaling that burning smell all day long. No wonder the staff all appeared to be smokers.

A man turned round when he heard us near the first of the kennels. He was holding a sweeping brush and regarded us with a sour glance, as if we had arrived at a prison outside visiting hours. ‘I want a big dog, a German Shepherd,’ I announced, quickly adding, ‘or a kind of German Shepherd,’ for fear the man would think I was a snob intent on a pedigree. ‘A big dog who likes running, I’m a runner.’ I realised I was sounding like a ten-year-old – I’ve always babbled when I’m nervous. And I was nervous, I wanted a dog, I didn’t want to leave that dreadful, sad place without a dog, the dog that I had been waiting for all my life.

‘There’s a fella there,’ said the man, half lifting his brush to point at a cage, and he asked if I considered the dog big enough for me. But it wasn’t a question; it was more like a challenge. A lone dog prowled a space that seemed too big for one, considering that in several of the nearby kennels eight or ten dogs were tumbling over each other in their desperation to catch a saviour’s eye, as if each stray knew they were trapped by a ticking clock. Five days to get a home or die. The solitary dog was medium-sized; black, a kind of skinny Labrador with small, mean eyes. He was cross-bred with something else, possibly a greyhound or a whippet. Whatever his origins, he was wary, suspicious. He looked fit, and was perhaps three or four years of age.

Not what I had had in mind, but then appearance isn’t everything. I went over to the cage, ‘Hi, boy,’ I said, thinking, ‘So this is it, the moment.’ It could have gone better. The dog snarled, threw his weight against the mesh and made sure I knew he was ready to rip my fingers off. ‘He’s bit vicious,’ said the man, enjoying his little joke, ‘but, sure, when you get him out running with you, he’ll be grand.’ The dog no doubt had a story but there was no one to tell it.

I said that I was thinking of something younger, more of a puppy and obviously not quite as aggressive, and oh, yes, a dog, not a female. I would have liked to shout at the cynical old son of a bitch, but Sophie’s kind, consummately civilised mother was standing beside me. The man pointed to some young pups, but assured me that they were all female. I don’t know why I was so intent on a male dog. The kennel they were in was overcrowded and soiled: no one could have kept the floor clean, as the puppies were falling over each other, playing, fighting, peeing. Two of them were very quiet, disturbingly subdued. A pretty, fox-coloured one with big white socks and a thick, black, fawn-and-white tail looked right at me and thrust a paw through the bars. The fur was soft but damp with urine; the puppy stared at me with large amber eyes. The black muzzle followed the paws through the bars. A girl in a white lab coat arrived with a small trolley holding several large metal dishes of food.

All the puppies dashed to the side of the kennel as the girl opened the door and pushed her trolley through. The little dog also joined the others, but quickly left the food and returned to where I was standing. I’ve never had any interest in jewellery but I noticed that the puppy’s black-ringed, burnished eyes were exactly the same colour as the smooth stone in Trudi’s silver ring. The puppy appeared to be wearing eyeliner and had delicate black eyebrows and beguiling ears that often stood to attention but also flopped over neatly. A very cute creature; a teddy bear of a dog, with a thick shawl of fur coming down from the back of the head, and over the neck to taper off halfway down the back.

The puppy jumped up and down as if she was trying to tell me something. She wanted me and it was decided. I would take her. I told the horrible little man that I had found a dog and went to open the cage. He stopped me, explaining that I had to go into the office and pay for her, then come back to him, but only if they agreed. There was a formal process. He seemed to enjoy his power. His eyes glittered when he looked at me and said that if I got approval...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.11.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Tiere / Tierhaltung | |

| Naturwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | animals • Behaviour • Dogs • Friendship • Human Condition |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-27785-3 / 0571277853 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-27785-8 / 9780571277858 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.