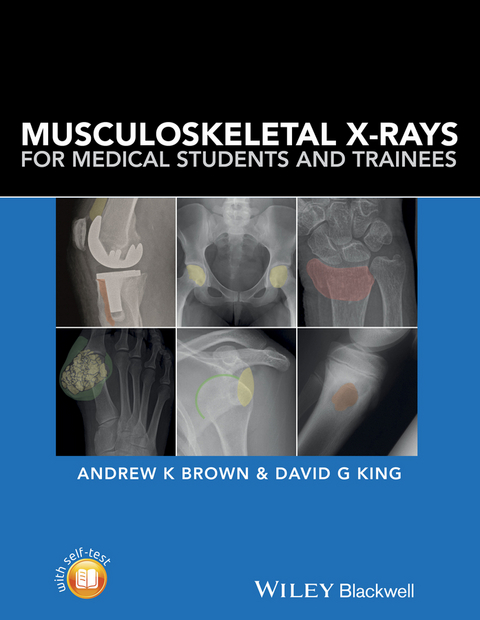

Musculoskeletal X-Rays for Medical Students and Trainees (eBook)

491 Seiten

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-45872-3 (ISBN)

Musculoskeletal X-rays for Medical Students:

• Presents each radiograph twice, side by side - once as would be seen in a clinical setting and again with clearly highlighted anatomy or pathology

• Focuses on radiographic appearances and abnormalities seen in common clinical presentations, highlighting key learning points relevant to each condition

• Covers introductory principles, normal anatomy and common pathologies, in addition to disease-specific sections covering adult and paediatric practice

• Includes self-assessment to test knowledge and presentation techniques

Musculoskeletal X-rays for Medical Students is designed for medical students, junior doctors, nurses and radiographers, and is ideal for both study and clinical reference.

Dr Andrew Brown is a Consultant Rheumatologist and Senior Lecturer in Medical Education at Hull York Medical School, and as such is involved in all aspects of undergraduate and postgraduate education with an emphasis on his clinical discipline of musculoskeletal medicine.

Dr David King is a Consultant Musculoskeletal Radiologist based at The York Teaching Hospital. He teaches musculoskeletal radiology to medical students, trainees in radiology, orhopaedics and emergency medicine, as well as professionals allied to medicine.

Musculoskeletal X-rays for Medical Students provides the key principles and skills needed for the assessment of normal and abnormal musculoskeletal radiographs. With a focus on concise information and clear visual presentation, it uses a unique colour overlay system to clearly present abnormalities. Musculoskeletal X-rays for Medical Students: Presents each radiograph twice, side by side once as would be seen in a clinical setting and again with clearly highlighted anatomy or pathology Focuses on radiographic appearances and abnormalities seen in common clinical presentations, highlighting key learning points relevant to each condition Covers introductory principles, normal anatomy and common pathologies, in addition to disease-specific sections covering adult and paediatric practice Includes self-assessment to test knowledge and presentation techniques Musculoskeletal X-rays for Medical Students is designed for medical students, junior doctors, nurses and radiographers, and is ideal for both study and clinical reference.

Dr Andrew Brown is a Consultant Rheumatologist and Senior Lecturer in Medical Education at Hull York Medical School, and as such is involved in all aspects of undergraduate and postgraduate education with an emphasis on his clinical discipline of musculoskeletal medicine. Dr David King is a Consultant Musculoskeletal Radiologist based at The York Teaching Hospital. He teaches musculoskeletal radiology to medical students, trainees in radiology, orhopaedics and emergency medicine, as well as professionals allied to medicine.

Preface, vii

Acknowledgements, viii

Part 1: Introduction, 1

1 Musculoskeletal X?-rays, 3

Introduction, 3

Basic principles of requesting plain radiographs of bones and joints, 4

Basic principles of examining and reporting plain radiographs of bones and joints, 6

Normal anatomy on musculoskeletal X-rays, 8

Part 2: Pathology, 21

2 Trauma, 23

Bone and joint injuries, 23

Specific injuries, 41

Spine, 58

Paediatric fractures, 67

Fractures in child abuse, 73

Further reading, 76

3 Arthritis, 77

Osteoarthritis, 77

Rheumatoid arthritis, 80

Crystal arthropathy, 83

Gout, 83

Calcium pyrophosphate disease, 86

Psoriatic arthritis, 91

Axial spondyloarthritis (ankylosing spondylitis), 95

4 Tumours and tumour?-like lesions, 98

Radiological evaluation of the patient, 98

X-rays - general principles, 101

Malignant tumours, 105

Bone metastases, 105

Multiple myeloma, 107

Plasmacytoma, 108

Osteosarcoma, 110

Chondrosarcoma, 111

Ewing's sarcoma, 113

Benign tumours, 114

Exostosis (Osteochondroma), 115

Osteoid osteoma, 116

Tumour?-like lesions, 117

Simple bone cyst, 118

Infection, 119

5 Metabolic bone disease, 120

Osteoporosis, 120

Osteomalacia, 121

Hyperparathyroidism, 122

Chronic kidney disease metabolic bone disorder, 124

Haemochromatosis, 126

6 Infection, 128

Routes of spread, 128

Causative organisms, 128

Osteomyelitis, 129

Septic arthritis, 134

Infective discitis, 136

7 Non?-traumatic paediatric conditions, 138

Developmental dysplasia of the hip, 138

Perthes' disease, 140

Tarsal coalition, 141

Osteochondritis dissecans, 143

8 Other bone pathology, 144

Paget's disease of bone, 144

Hypertrophic Osteoarthropathy (HOA), 147

Avascular necrosis, 147

9 Joint replacement, 149

Hardware failure and aseptic loosening, 149

Infection, 154

Malalignment and instability, 155

Periprosthetic fracture, 156

Part 3, 157

Self-assessment questions, 159

Self-assessment answers, 172

Index, 185

1

Musculoskeletal X‐rays

Introduction

Despite the availability of a wide range of imaging techniques to visualise musculoskeletal structures, plain radiographs or X‐rays remain an important and widely used first‐line investigation. It is probably the most readily available and least expensive imaging modality and is easily accessible to patients and healthcare professionals. As such, all medical professionals require at least a basic level of knowledge and training in the fundamental principles of requesting, interpreting and reporting plain radiographs of bones and joints.

Basic principles of requesting plain radiographs of bones and joints

Which structures?

Before requesting an X‐ray, the clinician should already have a good idea of the likely nature of the clinical problem and which musculoskeletal structures may be affected and what may or may not be visualised on an X‐ray. For example, radiographs are best at detecting pathological changes in bones, joints and cartilage, such as joint space narrowing, fracture, subluxation and dislocation. However, many soft tissue structures such as ligaments, tendons and synovium are not well visualised, and alternative imaging may be more appropriate to provide additional useful information to aid diagnosis and treatment.

Clinical assessment including the patient’s symptoms and a physical examination will usually determine the site or region that is to be evaluated by X‐ray. Exceptions may include a patient with rheumatoid arthritis where X‐rays of both hands and feet may be used to evaluate the extent of disease or structural damage which may be repeated serially to compare any disease progression over time.

Which views?

It is important to consider which views are chosen to visualise a particular region of interest. This is because the X‐ray beam creates a two dimensional shadow of a structure so selecting the correct view will maximise sensitivity. A basic principle is that two views should be requested, ideally 90° apart, which are usually obtained in antero‐posterior (AP) and lateral or oblique views. This is particularly important in a trauma context where fracture or dislocation may be missed if only a single view is acquired but may be less important for the assessment of arthritis. There are a number of established techniques and protocols for optimal image acquisition using standardised views of most musculoskeletal sites. Specialist views may also be considered in particular clinical situations, such as a ‘skyline view’ for the patello‐femoral joint or ‘through‐mouth view’ for the cervical spine. As well as the particular plane used to acquire the radiographic image, the position of the patient should also be considered. For example, weight‐bearing views with the patient in a standing position are often much more informative in evaluating cartilage loss in the knees of a patient with osteoarthritis or in providing additional information concerning biomechanical changes in the feet.

Compare both sides and review previous images

Particularly in equivocal cases, it may be informative to compare findings in a symptomatic area with the same region on the opposite side of the body or to look at the same region on a previous X‐ray. For example, in a patient with hip pain, an AP X‐ray of the pelvis allows some comparison between both hip joints, or in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, comparison with a previous X‐ray of the hands allows interpretation of any progression of erosive joint damage.

Correlation with clinical and other imaging findings

Any X‐ray findings always need to be interpreted in clinical context, with an individual’s symptoms, clinical examination findings and any other investigation results in mind. It may be necessary to perform additional imaging using alternative techniques such as ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, which may offer important additional or confirmatory information. Discussion with a specialist musculoskeletal radiologist is frequently helpful, and sharing and reviewing more challenging cases at a musculoskeletal radiology meeting involving clinicians and radiologists are often productive.

Safety considerations

Whilst undertaking a radiographic assessment is a well‐regulated process and is generally considered safe, it is important to remember that the procedure exposes a patient to ionising radiation and a number of important safety precautions need to be considered. This is particularly important in children and young adults and when the area includes any organ which is more sensitive to ionising radiation such as the thyroid, breasts or gonads. In women of childbearing age if the area involves the abdomen, spine or pelvis, it is essential to ask the patient about the possibility of pregnancy and an X‐ray in these circumstances should only be performed if absolutely necessary, such as a suspected pelvic fracture.

The amount of radiation exposure varies depending on the structure being visualised. Radiographs of deeper structures, such as the pelvis or lumbar spine, subject the patient to considerably greater radiation exposure than that of more peripheral structures, such as an examination of a single limb joint. The number of views and images obtained are proportional to the amount of radiation received. In all circumstances, it is important to be able to justify any radiation exposure on the basis of potential risk and benefit. The Department of Health Policy on Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000 [1] covers these aspects in detail.

Basic principles of examining and reporting plain radiographs of bones and joints

Everyone should have a straightforward strategy for reviewing and interpreting musculoskeletal X‐rays, including some basic principles and a systematic approach that can be routinely followed. It can often feel intimidating to review, interpret and describe an X‐ray, but this need not be complex or jargon‐heavy and confident use of simple descriptive language is all that is required. Undoubtedly, knowledge of musculoskeletal anatomy and understanding of pathological processes affecting bone, cartilage, joints and soft tissues will help, but a lot of information can be gained from describing any obvious abnormal or different appearances using simple descriptions, words and phrases. Even if you see an abnormality, it is still important to continue to evaluate the whole X‐ray in case other findings are present. If an obvious change is not present or immediately apparent, then it is useful to be able to fall back on a standard framework with which to organise your thoughts and report your observations. An example of such an approach is outlined as follows:

- Check patient identification details and labelling.

Do the patient and X‐ray identification details correspond, is it the correct X‐ray being viewed, date and time, left or right?

- Is the image quality satisfactory? Are imaging angles optimal?

Consider densities, penetration and blackening of film (see “X‐ray densities” below) and any inappropriate rotation and viewing angles. Also consider all additional views and patient position, has the region of interest been included?

X‐ray densities

To understand the appearance of different densities on an X‐ray, it is useful to consider the basic concept of how it has been produced. The image is essentially a shadow made by sending X‐rays through an area of the body onto a detector behind. For about 100 years, the detector used was film. More recently, film has been swapped for electronic digital detectors but the concept remains the same. Where there is only air between the X‐ray source and the detector, such as in the area around a limb, the film will be very exposed, that is blackened. Dense structures, such as bone, will stop most X‐rays and the film will be less exposed, that is more white. Soft tissues produce intermediate shades of grey.

Assuming there is no metallic foreign body or other man‐made artefact, there are only four densities to think about on an X‐ray: calcium is white and gas is black. Of the soft tissues, fat is a darker shade of grey because it is a little less dense to X‐rays than other soft tissues. All other soft tissues are the same lighter shade of grey, as is fluid (see Figure 1.1).

- Describe any obvious abnormality using simple descriptive language.

Name the specific bone (e.g. right tibia) and describe the location of any abnormality (e.g. proximal, middle or distal; head, neck or shaft; cortex or medulla). Basic terminology used for the paediatric and adult skeleton is shown in Figure 1.2. A combination of these terms and specific anatomical names should be used.

- Use a systematic approach to consider specific musculoskeletal structures (bones, joints, cartilage and soft tissues).

- Bone alignment – are there any changes in position which may suggest a fracture or dislocation?

- Bone cortices – follow the outline of each bone as any breach in the cortex may indicate a fracture or an erosive arthritis.

- Bone texture – Altered density or disruption in the usual trabecular pattern within the substance of the bone may indicate pathology.

- Joint and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.6.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Orthopädie |

| Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Radiologie / Bildgebende Verfahren ► Radiologie | |

| Schlagworte | Adult • anatomy • Assessment • Clinical disease • Imaging • Junior Doctor • medical education • Medical Science • medical student • Medizin • Medizinstudium • Musculoskeletal • Nurse • Paediatric • Pathology • Pediatric • Radiograph • radiographer • Radiologie • Radiologie u. Bildgebende Verfahren • Radiology & Imaging • X-Ray • XRay |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-45872-9 / 1118458729 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-45872-3 / 9781118458723 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich