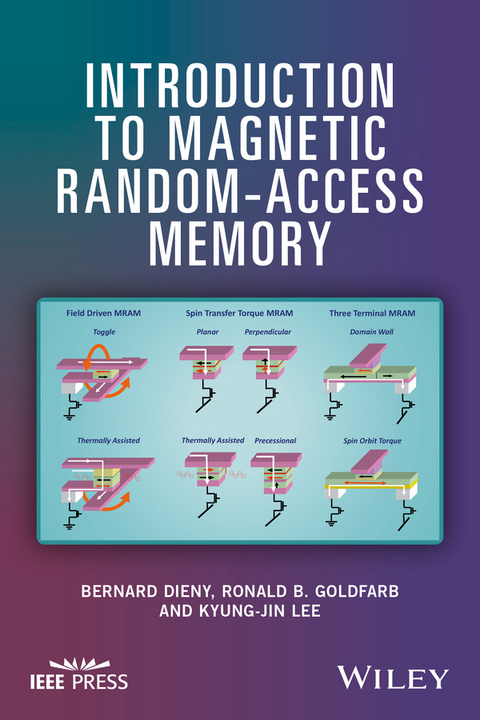

Magnetic random-access memory (MRAM) is poised to replace traditional computer memory based on complementary metal-oxide semiconductors (CMOS). MRAM will surpass all other types of memory devices in terms of nonvolatility, low energy dissipation, fast switching speed, radiation hardness, and durability. Although toggle-MRAM is currently a commercial product, it is clear that future developments in MRAM will be based on spin-transfer torque, which makes use of electrons' spin angular momentum instead of their charge. MRAM will require an amalgamation of magnetics and microelectronics technologies. However, researchers and developers in magnetics and in microelectronics attend different technical conferences, publish in different journals, use different tools, and have different backgrounds in condensed-matter physics, electrical engineering, and materials science.

This book is an introduction to MRAM for microelectronics engineers written by specialists in magnetic materials and devices. It presents the basic phenomena involved in MRAM, the materials and film stacks being used, the basic principles of the various types of MRAM (toggle and spin-transfer torque; magnetized in-plane or perpendicular-to-plane), the back-end magnetic technology, and recent developments toward logic-in-memory architectures. It helps bridge the cultural gap between the microelectronics and magnetics communities.Magnetic random-access memory (MRAM) is poised to replace traditional computer memory based on complementary metal-oxide semiconductors (CMOS). MRAM will surpass all other types of memory devices in terms of nonvolatility, low energy dissipation, fast switching speed, radiation hardness, and durability. Although toggle-MRAM is currently a commercial product, it is clear that future developments in MRAM will be based on spin-transfer torque, which makes use of electrons spin angular momentum instead of their charge. MRAM will require an amalgamation of magnetics and microelectronics technologies. However, researchers and developers in magnetics and in microelectronics attend different technical conferences, publish in different journals, use different tools, and have different backgrounds in condensed-matter physics, electrical engineering, and materials science. This book is an introduction to MRAM for microelectronics engineers written by specialists in magnetic materials and devices. It presents the basic phenomena involved in MRAM, the materials and film stacks being used, the basic principles of the various types of MRAM (toggle and spin-transfer torque; magnetized in-plane or perpendicular-to-plane), the back-end magnetic technology, and recent developments toward logic-in-memory architectures. It helps bridge the cultural gap between the microelectronics and magnetics communities.

Bernard Dieny has conducted research in magnetism for 30 years. He played a key role in the pioneering work on spin-valves at IBM Almaden Research Center in 1990-1991. In 2001, he co-founded SPINTEC in Grenoble, France, a public research laboratory devoted to spin-electronic phenomena and components. Dieny is co-inventor of 70 patents and has co-authored more than 340 scientific publications. He received an outstanding achievement award from IBM in 1992 for the development of spin-valves, the European Descartes Prize for Research in 2006, and two Advanced Research Grants from the European Research Council in 2009 and 2015. He is co-founder of two companies, one dedicated to magnetic random-access memory, Crocus Technology, the other to the design of hybrid CMOS/magnetic circuits, EVADERIS. In 2011 he was elected Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Ronald B. Goldfarb was leader of the Magnetics Group at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado, USA, from 2000 to 2015. He has published over 60 papers, book chapters, and encyclopedia articles in the areas of magnetic measurements, superconductor characterization, and instrumentation. In 2004 he was elected Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). From 1995 to 2004 he was editor in chief of IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. He is the founder and chief editor of IEEE Magnetics Letters, established in 2010. He received the IEEE Magnetics Society Distinguished Service Award in 2016. Kyung-Jin Lee is a professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and an adjunct professor of the KU-KIST Graduate School of Converging Science and Technology, at Korea University. Before joining the university, he worked for Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology in the areas of magnetic recording and magnetic random-access memory. His current research is focused on understanding the underlying physics of current-induced magnetic excitations and exploring new spintronic devices utilizing spin-transfer torque. He is co-inventor of 20 patents and has more than 100 scientific publications in the areas of magnetic random-access memory, spin-transfer torque, and spin-orbit torques. He received an outstanding patent award from the Korea Patent Office in 2005 and an award for Excellent Research on Basic Science from the Korean government in 2010. In 2013 he was recognized by the National Academy of Engineering of Korea as a leading scientist in spintronics, "one of the top 100 technologies of the future."

ABOUT THE EDITORS xi

PREFACE xiii

CHAPTER 1 BASIC SPINTRONIC TRANSPORT PHENOMENA 1

Nicolas Locatelli and Vincent Cros

1.1 Giant Magnetoresistance 2

1.2 Tunneling Magnetoresistance 9

1.3 The Spin-Transfer Phenomenon 20

CHAPTER 2 MAGNETIC PROPERTIES OF MATERIALS FOR MRAM 29

Shinji Yuasa

2.1 Magnetic Tunnel Junctions for MRAM 29

2.2 Magnetic Materials and Magnetic Properties 31

2.3 Basic Materials and Magnetotransport Properties 39

CHAPTER 3 MICROMAGNETISM APPLIED TO MAGNETIC NANOSTRUCTURES 55

Liliana D. Buda-Prejbeanu

3.1 Micromagnetic Theory: From Basic Concepts Toward the Equations 55

3.2 Micromagnetic Configurations in Magnetic Circular Dots 67

3.3 STT-Induced Magnetization Switching: Comparison of Macrospin and Micromagnetism 70

3.4 Example of Magnetization Precessional STT Switching: Role of Dipolar Coupling 73

CHAPTER 4 MAGNETIZATION DYNAMICS 79

William E. Bailey

4.1 Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert Equation 79

4.2 Small-Angle Magnetization Dynamics 84

4.3 Large-Angle Dynamics: Switching 90

4.4 Magnetization Switching by Spin-Transfer 95

CHAPTER 5 MAGNETIC RANDOM-ACCESS MEMORY 101

Bernard Dieny and I. Lucian Prejbeanu

5.1 Introduction to Magnetic Random-Access Memory (MRAM) 101

5.2 Storage Function: MRAM Retention 104

5.3 Read Function 110

5.4 Field-Written MRAM (FIMS-MRAM) 112

5.5 Spin-Transfer Torque MRAM (STT-MRAM) 118

5.6 Thermally-Assisted MRAM (TA-MRAM) 135

5.7 Three-Terminal MRAM Devices 150

5.8 Comparison of MRAM with Other Nonvolatile Memory Technologies 153

5.9 Conclusion 157

CHAPTER 6 MAGNETIC BACK-END TECHNOLOGY 165

Michael C. Gaidis

6.1 Magnetoresistive Random-Access Memory (MRAM) Basics 165

6.2 MRAM Back-End-of-Line Structures 166

6.3 MRAM Process Integration 169

6.4 Process Characterization 187

CHAPTER 7 BEYOND MRAM: NONVOLATILE LOGIC-IN-MEMORY VLSI 199

Takahiro Hanyu, Tetsuo Endoh, Shoji Ikeda, Tadahiko Sugibayashi, Naoki Kasai, Daisuke Suzuki, Masanori Natsui, Hiroki Koike, and Hideo Ohno

7.1 Introduction 199

7.2 Nonvolatile Logic-in-Memory Architecture 203

7.3 Circuit Scheme for Logic-in-Memory Architecture Based on Magnetic Flip-Flop Circuits 209

7.4 Nonvolatile Full Adder Using MTJ Devices in Combination with MOS Transistors 214

7.5 Content-Addressable Memory 217

7.6 MTJ-based Nonvolatile Field-Programmable Gate Array 224

APPENDIX 231

INDEX 233

Preface

A Perspective on Nonvolatile Magnetic Memory Technology

As context for this book, computer memory hierarchy ranges from cache (fastest and most expensive) to main memory, to mass storage (slowest and least expensive). Cache memory, immediately accessible by the central processing unit, is usually static random-access memory (SRAM). Main memory is usually dynamic random-access memory (DRAM); like SRAM, it requires power to maintain its memory state, but additionally must be electrically refreshed, typically every 64 ms (1). Mass storage is exemplified by nonvolatile flash memory (of the NAND and NOR varieties) and magnetic hard-disk drives.

Although magnetic random-access memory (MRAM), in particular spin-transfer torque MRAM (STT-MRAM), has the potential to serve as a universal computer memory—cache, main memory, and mass storage—it will likely be most cost-effective as main memory. MRAM is already a commercial product, albeit expensive and of low density relative to DRAM, and several variations of STT-MRAM are in development. Particular interest is in the superior performance of STT-MRAM with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Still under research are three-terminal spin–orbit torque MRAM (2,3), which has high endurance and separate paths for read and write current, and voltage-controlled magnetoelectric MRAM (4–7), which has low energy requirements.

More generally, MRAM, the subject of this book, is characterized by nonvolatility, low energy dissipation, high endurance (repeated writing), scalability to advanced (sub-20 nm) technology nodes, compatibility with complementary metal–oxide semiconductor (CMOS) processing, resistance to radiation damage, and short read and write times. The most intriguing of these, nonvolatility and low energy dissipation, are the main drivers of the technology.

Details of a 1024 bit core plane memory module (11). When magnetic-core memory was introduced in the mid-1950s, toroid cores were about 2 mm in outer diameter.

Nonvolatile MRAM is not really new. It was first developed in the early 1950s by Jay W. Forrester at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (8,9). As envisioned by Forrester, a three-dimensional magnetic-core memory module consisted of circumferentially magnetized toroids strung with x-, y-, and z-plane select wires and a fourth inductively driven output-signal wire. Switching times of the original material studied by Forrester, grain-oriented Ni50Fe50 “Deltamax,” were on the order of 10 ms. He noted that nonmetallic magnetic ferrites would switch in less than 1 μs based on materials research by William N. Papian (10), and that is how the technology developed. The estimated cost per bit was $1 ($9 today, adjusted for monetary inflation).

Another form of nonvolatile magnetic memory was developed by Andrew H. Bobeck and colleagues at Bell Laboratories in the late 1960s and early 1970s for mass storage: magnetic bubble memory (12,13). It was based on sequential, not random, access. Magnetic bubble domains in synthetic garnets with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy were stabilized by bias fields from permanent magnets. The presence or absence of a bubble—a logic “1” or “0”—was detected with magnetoresistive sensors. Bubbles could be generated, propagated, transferred, replicated, stored, and annihilated. Two orthogonal drive coils provided an in-plane rotating magnetic field to control the magnetization of Ni-Fe bubble-propagation elements (14).

The advent of DRAM in the 1970s, which sacrificed nonvolatility for reduced size, higher speed, and reduced cost, made core memory obsolete for main memory. By the early 1980s, storage density advances and cost reductions in hard-disk drives made bubble memory obsolete for mass storage (although bubble memory continued to be used in military and aerospace applications that required ruggedness).

Besides MRAM, other forms of nonvolatile memory are subjects of intense research. They are based on binary state variables that include “spin, phase, multipole orientation, mechanical position, polarity, orbital symmetry, magnetic flux quanta, molecular configuration, and other quantum states” (15). Mechanisms with great potential include resistive RAM (“memristors”) (16) and phase-change RAM (17). One of these may eventually become the dominant technology for cache memory, main memory, or mass storage, but for now, MRAM seems the most promising for main memory. Nevertheless, alternatives to MRAM should not be discounted (18,19).

Schematic diagram of the first commercial magnetic bubble memory module, TIB0103, manufactured in 1977 (14). Shown are the bias magnets, drive coils, control and interface circuits, bubble chip, and Ni-Fe “T-bar” bubble-propagation pattern. (An asymmetric chevron pattern was used instead in the TIB0203 in 1978.) The magnetic bubble diameter was 5 μm. The chip had 92,000 bits, a storage density of 155,000 bits/cm2, an access time of 2–4 ms, and a data transfer rate of 50,000 bits/s.

Coincident with the memory revolution is a rethinking of computer logic and architecture, particularly to address problems of energy consumption in supercomputers and massive data centers. For example, in the United States, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) has sponsored the development of a prototype cryogenic computer under its “Cryogenic Computing Complexity” program (20). Dramatic reductions are projected in both energy consumption and size (21). Such a computer would combine superconducting, single flux quantum (SFQ) logic with hybrid superconducting/magnetic RAM. Hybrid superconducting/magnetic Josephson junctions switched by spin-transfer torque, resulting in measureable changes in critical current, have been demonstrated (22).

Recent accelerated growth in data centers and their demand for energy are bringing the need for new computer logic and memory to a head. World Wide Web search engines have resorted to storing most of their data in energy-inefficient DRAM (23) because retrieval from mass storage is too slow. There is a need to prototype, test, and benchmark (24) the energy dissipation, high-speed performance, reliability, dimensional scalability, temperature margins, and fabrication reproducibility of MRAM materials, devices, and circuits. Inevitably, new physical phenomena arise as nanostructures shrink in size, and failures will be determined by unknown variables and the increased relative importance of uncontrolled edge properties with respect to the bulk (25).

Nanopillar Josephson junction with a Ni0.8Fe0.2/Cu/Ni pseudo-spin valve (PSV) barrier (left) and voltage versus current at 4 K and zero applied field for parallel and antiparallel magnetic states (right) (22).

This book is designed for microelectronics engineers who need a working knowledge of magnetic memory devices. As conceived by one of the editors, Bernard Dieny, it aims to promote synergy between researchers and developers working in the field of electron devices and those in magnetics and information storage.

The chapters in this volume cover basic concepts in spin electronics (spintronics); magnetic properties of materials; micromagnetic modeling; dynamics of magnetic precession and damping; different implementations of MRAM; the integration of MRAM with CMOS; and future hybrid logic-in-memory architectures.

The authors are leaders in their respective fields. Nicolas Locatelli and Vincent Cros are known for their major contributions in the field of spin torque nano-oscillators and nanodevices assembled in novel computer architectures (26,27). Shinji Yuasa is noted for his pioneering experimental work (28,29) on giant magnetoresistance in magnetic tunnel junctions with MgO barriers (30,31). Liliana Buda-Prejbeanu is expert in micromagnetic modeling and computational magnetics (32). Bill Bailey is an authority on magnetization dynamics and spin–orbit coupling (33). Bernard Dieny is famous for his key role in the discovery of giant magnetoresistance in spin valve structures (34,35). Lucian Prejbeanu is known for his work on thermally assisted MRAM (36). Michael Gaidis is a microwave engineer who has specialized in “back-end-of-line” integration of MRAM with CMOS (37). The chapter on nonvolatile logic-in-memory (38,39) by Takahiro Hanyu, Hideo Ohno, and the team at Tohoku University represents one of the most complete compilations on this topical subject.

This book was sponsored by the IEEE Magnetics Society and published under the Wiley-IEEE Press imprint. The editor at Wiley-IEEE Press was Mary Hatcher.

Ronald B. Goldfarb

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Boulder, Colorado, USA

Note

The preface is a contribution of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, not subject to copyright.

References

- 1. I. Bhati, M.-T. Chang, Z. Chishti, S.-L. Lu, and B. Jacob, “DRAM refresh mechanisms, penalties, and trade-offs,” IEEE Trans. Comput. 65, pp. 108–121 (2016); doi: 10.1109/TC.2015.2417540.

- 2. I. M. Miron, K. Garello, G. Gaudin, P.-J. Zermatten, M. V. Costache, S. Auffret, S. Bandiera, B. Rodmacq, A. Schuhl, and P. Gambardella, “Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection,” Nature 476, pp. 189–194 (2011); doi: 10.1038/nature10309.

- 3. L.-Q. Liu, C.-F. Pai, Y. Li, H. W. Tseng, D....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.11.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Informatik ► Weitere Themen ► Hardware |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Atom- / Kern- / Molekularphysik | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Festkörperphysik | |

| Technik ► Elektrotechnik / Energietechnik | |

| Schlagworte | Electrical & Electronics Engineering • Elektrotechnik u. Elektronik • fundamentals of magnetic materials • fundamentals of magnetic technology • fundamentals of MRAM • Halbleiter • Halbleiterphysik • introduction to MRAM • Magnetic random access memory • Magnetics • magnetism • Magnetismus • microelectronics • MRAM • Physics • Physik • Semiconductor physics • semiconductors |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-07944-6 / 1119079446 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-07944-6 / 9781119079446 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich