Meta-Analysis (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-95782-0 (ISBN)

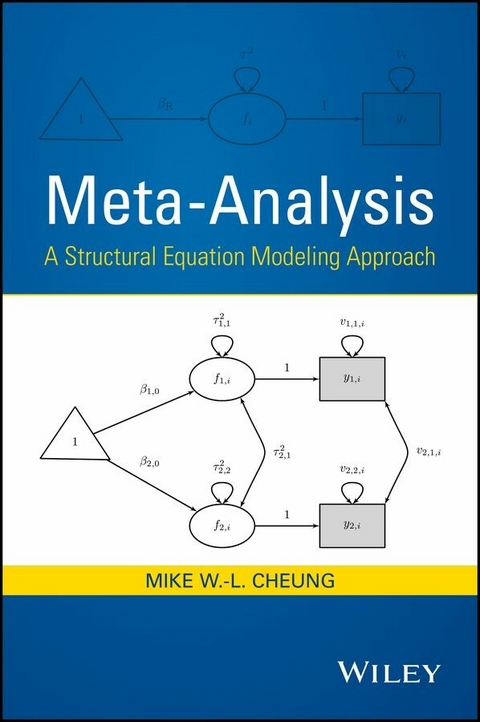

Presents a novel approach to conducting meta-analysis using structural equation modeling.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) and meta-analysis are two powerful statistical methods in the educational, social, behavioral, and medical sciences. They are often treated as two unrelated topics in the literature. This book presents a unified framework on analyzing meta-analytic data within the SEM framework, and illustrates how to conduct meta-analysis using the metaSEM package in the R statistical environment.

Meta-Analysis: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach begins by introducing the importance of SEM and meta-analysis in answering research questions. Key ideas in meta-analysis and SEM are briefly reviewed, and various meta-analytic models are then introduced and linked to the SEM framework. Fixed-, random-, and mixed-effects models in univariate and multivariate meta-analyses, three-level meta-analysis, and meta-analytic structural equation modeling, are introduced. Advanced topics, such as using restricted maximum likelihood estimation method and handling missing covariates, are also covered. Readers will learn a single framework to apply both meta-analysis and SEM. Examples in R and in Mplus are included.

This book will be a valuable resource for statistical and academic researchers and graduate students carrying out meta-analyses, and will also be useful to researchers and statisticians using SEM in biostatistics. Basic knowledge of either SEM or meta-analysis will be helpful in understanding the materials in this book.

Mike W.-L. Cheung, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Presents a novel approach to conducting meta-analysis using structural equation modeling. Structural equation modeling (SEM) and meta-analysis are two powerful statistical methods in the educational, social, behavioral, and medical sciences. They are often treated as two unrelated topics in the literature. This book presents a unified framework on analyzing meta-analytic data within the SEM framework, and illustrates how to conduct meta-analysis using the metaSEM package in the R statistical environment. Meta-Analysis: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach begins by introducing the importance of SEM and meta-analysis in answering research questions. Key ideas in meta-analysis and SEM are briefly reviewed, and various meta-analytic models are then introduced and linked to the SEM framework. Fixed-, random-, and mixed-effects models in univariate and multivariate meta-analyses, three-level meta-analysis, and meta-analytic structural equation modeling, are introduced. Advanced topics, such as using restricted maximum likelihood estimation method and handling missing covariates, are also covered. Readers will learn a single framework to apply both meta-analysis and SEM. Examples in R and in Mplus are included. This book will be a valuable resource for statistical and academic researchers and graduate students carrying out meta-analyses, and will also be useful to researchers and statisticians using SEM in biostatistics. Basic knowledge of either SEM or meta-analysis will be helpful in understanding the materials in this book.

Mike W.-L. Cheung, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Preface xiii

Acknowledgments xv

List of abbreviations xvii

List of figures xix

List of tables xxi

1 Introduction 1

1.1 What is meta-analysis? 1

1.2 What is structural equation modeling? 2

1.3 Reasons for writing a book on meta-analysis and structural equation modeling 3

1.4 Outline of the following chapters 6

1.5 Concluding remarks and further readings 8

2 Brief review of structural equation modeling 13

2.1 Introduction 13

2.2 Model specification 14

2.3 Common structural equation models 18

2.4 Estimation methods, test statistics, and goodness-of-fit indices 25

2.5 Extensions on structural equation modeling 38

2.6 Concluding remarks and further readings 42

3 Computing effect sizes for meta-analysis 48

3.1 Introduction 48

3.2 Effect sizes for univariate meta-analysis 50

3.3 Effect sizes for multivariate meta-analysis 57

3.4 General approach to estimating the sampling variances and covariances 60

3.5 Illustrations Using R 68

3.6 Concluding remarks and further readings 78

4 Univariate meta-analysis 81

4.1 Introduction 81

4.2 Fixed-effects model 83

4.3 Random-effects model 87

4.4 Comparisons between the fixed- and the random-effects models 93

4.5 Mixed-effects model 96

4.6 Structural equation modeling approach 100

4.7 Illustrations using R 105

4.8 Concluding remarks and further readings 116

5 Multivariate meta-analysis 121

5.1 Introduction 121

5.2 Fixed-effects model 124

5.3 Random-effects model 127

5.4 Mixed-effects model 134

5.5 Structural equation modeling approach 136

5.6 Extensions: mediation and moderation models on the effect sizes 140

5.7 Illustrations using R 145

5.8 Concluding remarks and further readings 174

6 Three-level meta-analysis 179

6.1 Introduction 179

6.2 Three-level model 183

6.3 Structural equation modeling approach 188

6.4 Relationship between the multivariate and the three-level meta-analyses 195

6.5 Illustrations using R 200

6.6 Concluding remarks and further readings 210

7 Meta-analytic structural equation modeling 214

7.1 Introduction 214

7.2 Conventional approaches 218

7.3 Two-stage structural equation modeling: fixed-effects models 223

7.4 Two-stage structural equation modeling: random-effects models 233

7.5 Related issues 235

7.6 Illustrations using R 244

7.7 Concluding remarks and further readings 273

8 Advanced topics in SEM-based meta-analysis 279

8.1 Restricted (or residual) maximum likelihood estimation 279

8.2 Missing values in the moderators 289

8.3 Illustrations using R 294

8.4 Concluding remarks and further readings 309

9 Conducting meta-analysis with Mplus 313

9.1 Introduction 313

9.2 Univariate meta-analysis 314

9.3 Multivariate meta-analysis 327

9.4 Three-level meta-analysis 346

9.5 Concluding remarks and further readings 353

A A brief introduction to R, OpenMx, and metaSEM packages 356

A.1 R 357

A.2 OpenMx 362

A.3 metaSEM 364

References 368

Index 369

"This book will be a valuable resource for statistical and academic researchers and graduate students carrying out meta-analyses, and will also be useful to researchers and statisticians using SEM in biostatistics. cover, would sit well on the bookshelves of those interested in this increasingly important field of scientific endeavour." (Zentralblatt MATH, 1 June 2015)

Chapter 1

Introduction

This chapter gives an overview of this book. It first briefly reviews the history and applications of meta-analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM). The importance of using meta-analysis and SEM to advancing scientific research is discussed. This chapter then addresses the needs and advantages of integrating meta-analysis and SEM. It further outlines the remaining chapters and the data sets used in the book. We close this chapter by addressing topics that will not be further discussed in this book.

1.1 What is meta-analysis?

Pearson (1904) was often credited as one of the earliest researchers applying ideas of meta-analysis (e.g., Chalmers et al., 2002; Cooper and Hedges, 2009; National Research Council, 1992; O'Rourke, 2007). He tried to determine the relationship between mortality and inoculation with a vaccine for enteric fever by averaging correlation coefficients across 11 small-sample studies. The idea of combining and pooling studies has been widely used in the physical and social sciences. There are many successful stories as documented in, for example, National Research Council (1992) and Hunt (1997). The term meta-analysis was coined by Gene Glass in educational psychology to represent “the statistical analysis of a large collection of analysis results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings” (Glass 1976, p.3).

Validity generalization, another technique with similar objectives, was independently developed by Schmidt and Hunter (1977) in industrial and organizational psychology in nearly the same period. Later, Hedges and Olkin (1985) wrote a classic text that provides the statistical foundation of meta-analysis. These techniques have been expanded, refined, and adopted in many disciplines. Meta-analysis is now a popular statistical technique to synthesizing research findings in many disciplines including educational, social, and medical sciences.

A meta-analysis begins by conceptualizing the research questions. The research questions must be empirically testable based on the published studies. The published studies should be able to provide enough information to calculate the effect sizes, the ingredients for a meta-analysis. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are developed to guide which studies are eligible to be included in the meta-analysis. After extracting the effect sizes and the study characteristics, the data can be subjected to a statistical analysis. The next step is to interpret the results and prepare reports to disseminate the findings.

This book mainly focuses on the statistical issues in a meta-analysis.Generally speaking, the statistical models discussed in this book fall into three dimensions:

- fixed-effects versus random-effects models;

- independent versus nonindependent effect sizes; and

- models with or without structural models on the averaged effect sizes.

The first dimension is fixed-effects versus random-effects models. Fixed-effects models provide conditional inferences on the studies included in the meta-analysis, while random-effects models attempt to generalize the inferences beyond the studies used in the meta-analysis. Statistically speaking, the fixed-effects models, also known as the common effects models, are special cases of the random-effects models.

The second dimension focuses on whether the effect sizes are independent or nonindependent. Most meta-analytic models, such as the univariate meta-analysis introduced in this book, assume independence on the effect sizes. When there is more than one effect size reported per study, the effect sizes are likely nonindependent. Both the multivariate and three-level meta-analyses are introduced to handle the nonindependent effect sizes depending on the assumptions of the data. The last dimension is whether the research questions are related to the averaged effect sizes themselves or some forms of structural models on the averaged effect sizes. If researchers are only interested in the effect sizes, conventional univariate, multivariate, and three-level meta-analyses are sufficient. Sometimes, researchers are interested in testing proposed structures on the effect size. This type of research questions can be addressed by testing the mediation and moderation models on the effect sizes (Section 5.6) or the meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM; Chapter 7).

1.2 What is structural equation modeling?

SEM is a flexible modeling technique to test proposed models. The proposed models can be specified as path diagrams, equations, or matrices. SEM integrates several statistical techniques into a single framework—path analysis in biology and sociology, factor analysis in psychology, and simultaneous equation and errors-in-variables models in economics (e.g., Matsueda 2012). Jöreskog (1969, 1970, 1978) was usually credited as the one who first integrated these techniques into a single framework. He further proposed computational feasible approaches to conduct the analysis. These algorithms were implemented in LISREL (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1996), the first SEM package in the market. At nearly the same time, Bentler contributed a lot in the methodological development of SEM (e.g., Bentler 1986, 1990; Bentler and Weeks, 1980). He also wrote a user friendly program called EQS (Bentler, 2006) to conduct SEM. The availability of LISREL and EQS popularized applications of SEM in various fields. Both Jöreskog and Bentler received the Award for Distinguished Scientific Applications of Psychology (American Psychological Association, 2007a, b) “[f]or [their] development of models, statistical procedures, and a computer algorithm for structural equation modeling (SEM) that changed the way in which inferences are made from observational data; namely, SEM permits hypotheses derived from theory to be tested.”

Many recent methodological advances have been developed and integrated into Mplus, a popular and powerful SEM package (Muthén and Muthén, 2012). SEM is now widely used as a statistical model to test research hypotheses. Readers may refer to, for example, MacCallum and Austin (2000) and Bollen (2002) for some applications in the social sciences.

1.3 Reasons for writing a book on meta-analysis and structural equation modeling

There are already many good books on the topic of meta-analysis (e.g., Borenstein et al., 2010; Card, 2012; Hedges and Olkin, 1985; Lipsey and Wilson, 2000; Schmidt and Hunter, 2015; Whitehead, 2002). Moreover, meta-analysis has also been covered as special cases of mixed-effects or multilevel models (e.g., Demidenko, 2013, Goldstein, 2011, Hox, 2010; Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). It seems that there is no need to write another book on meta-analysis. On the other hand, this book did not aim to be a comprehensive introduction to SEM neither. Before answering this question, let us first review the current state of applications of meta-analysis and SEM in academic research.

Figure 1.1 shows two figures on the numbers of publications using meta-analysis and SEM in Web of Science. The figures were averaged over 5 years. For example, the number for 2010 was calculated by averaging from 1998 to 2012. Figure 1.1a depicts the actual numbers of publications, while Figure 1.1b converts the numbers to percentages by dividing the numbers by the total numbers of publications. The trends in both figures are nearly identical in terms of actual numbers and percentages. One speculation why the numbers on meta-analysis are higher than those on SEM is that meta-analysis is very popular in medical research, whereas SEM is rarely used in medical research (cf. Song and Lee, 2012). Anyway, it is clear that both techniques are getting more and more popular over time.

Figure 1.1 Publications using meta-analysis and structural equation modeling. (a) Actual number of publications per year and (b) percentage of publications.

Although both SEM and meta-analysis are very popular in the educational, social, behavioral, and medical sciences, both techniques are treated as two unrelated techniques in the literature. They have their own assumptions, models, terminologies, software packages, communities, and even journals (Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal and Research Synthesis Methods). These two techniques are also considered as separate topics in doctoral training in psychology (Aiken et al., 2008). Users of SEM are mainly interested in primary research, while users of meta-analysis only conduct research synthesis on the literature. Researchers working in one area rarely refer to the work in the other area. Users of SEM seldom have the motivation to learn meta-analysis and vice versa. Advances in one area have basically no impact on the other area.

There were some attempts to bring these two techniques together. One such topic is known as MASEM (e.g., Cheung and Chan, 2005b; Viswesvaran and Ones, 1995). There are two stages involved in an MASEM. Meta-analysis is usually used to pool correlation matrices together in the stage 1 analysis. The pooled correlation matrix is used to fit structural equation models in the stage 2 analysis. As researchers usually apply ad hoc procedures to fit structural equation models, some of these procedures are not statistically defensible from an SEM perspective. Therefore, one of the goals of this book (Chapter 7) was to provide a statistically defensible approach to conduct...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.4.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Analysis |

| Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Statistik | |

| Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Wahrscheinlichkeit / Kombinatorik | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Allg. Naturwissenschaft • Angew. Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechn. u. Statistik / Modelle • Applied Probability & Statistics - Models • General Science • Metaanalyse • meta-analysis, structural equation models, statistics, R, educational science, social science, behavioral science, medical science • Statistics • Statistics for Social Sciences • Statistik • Statistik in den Sozialwissenschaften • Strukturgleichungsmodell |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-95782-2 / 1118957822 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-95782-0 / 9781118957820 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich