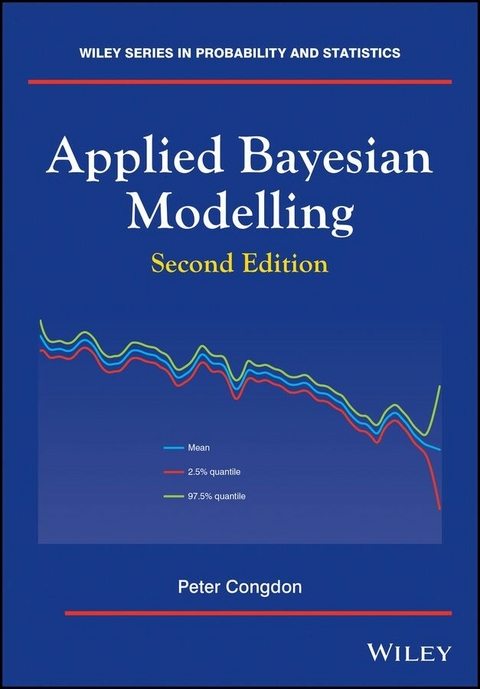

Applied Bayesian Modelling (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-89506-1 (ISBN)

This book provides an accessible approach to Bayesian computing and data analysis, with an emphasis on the interpretation of real data sets. Following in the tradition of the successful first edition, this book aims to make a wide range of statistical modeling applications accessible using tested code that can be readily adapted to the reader's own applications. The second edition has been thoroughly reworked and updated to take account of advances in the field. A new set of worked examples is included. The novel aspect of the first edition was the coverage of statistical modeling using WinBUGS and OPENBUGS. This feature continues in the new edition along with examples using R to broaden appeal and for completeness of coverage.

Peter Congdon is Research Professor of Quantitative Geography and Health Statistics at Queen Mary University of London. He has written three earlier books on Bayesian modelling and data analysis techniques with Wiley, and has a wide range of publications in statistical methodology and in application areas. His current interests include applications to spatial and survey data relating to health status and health service research.

"A nice guidebook to intermediate and advanced Bayesian models." (Scientific Computing, 13 January 2015)

Chapter 1

Bayesian methods and Bayesian estimation

1.1 Introduction

Bayesian analysis of data in the health, social and physical sciences has been greatly facilitated in the last two decades by improved scope for estimation via iterative sampling methods. Recent overviews are provided by Brooks et al. (2011), Hamelryck et al. (2012), and Damien et al. (2013). Since the first edition of this book in 2003, the major changes in Bayesian technology relevant to practical data analysis have arguably been in distinct new approaches to estimation, such as the INLA method, and in a much extended range of computer packages, especially in R, for applying Bayesian techniques (e.g. Martin and Quinn, 2006; Albert, 2007; Statisticat LLC, 2013).

Among the benefits of the Bayesian approach and of sampling methods of Bayesian estimation (Gelfand and Smith, 1990; Geyer, 2011) are a more natural interpretation of parameter uncertainty (e.g. through credible intervals) (Lu et al., 2012), and the ease with which the full parameter density (possibly skew or multi-modal) may be estimated. By contrast, frequentist estimates may rely on normality approximations based on large sample asymptotics (Bayarri and Berger, 2004). Unlike classical techniques, the Bayesian method allows model comparison across non-nested alternatives, and recent sampling estimation developments have facilitated new methods of model choice (e.g. Barbieri and Berger, 2004; Chib and Jeliazkov, 2005). The flexibility of Bayesian sampling estimation extends to derived ‘structural’ parameters combining model parameters and possibly data, and with substantive meaning in application areas, which under classical methods might require the delta technique. For example, Parent and Rivot (2012) refer to ‘management parameters’ derived from hierarchical ecological models.

New estimation methods also assist in the application of hierarchical models to represent latent process variables, which act to borrow strength in estimation across related units and outcomes (Wikle, 2003; Clark and Gelfand, 2006). Letting and denote joint and conditional densities respectively, the paradigm for a hierarchical model specifies

based on an assumption that observations are imperfect realisations of an underlying process and that units are exchangeable. Usually the observations are considered conditionally independent given the process and parameters.

Such techniques play a major role in applications such as spatial disease patterns, small domain estimation for survey outcomes (Ghosh and Rao, 1994), meta-analysis across several studies (Sutton and Abrams, 2001), educational and psychological testing (Sahu, 2002; Shiffrin et al., 2008) and performance comparisons (e.g. Racz and Sedransk, 2010; Ding et al., 2013).

The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methodology may also be used to augment the data, providing an analogue to the classical EM method. Examples of such data augmentation (with a missing data interpretation) are latent continuous data underlying binary outcomes (Albert and Chib, 1993; Rouder and Lu, 2005) and latent multinomial group membership indicators that underlie parametric mixtures. MCMC mixing may also be improved by introducing auxiliary variables (Gilks and Roberts, 1996).

1.1.1 Summarising existing knowledge: Prior densities for parameters

In classical inference the sample data are taken as random while population parameters , of dimension , are taken as fixed. In Bayesian analysis, parameters themselves follow a probability distribution, knowledge about which (before considering the data at hand) is summarised in a prior distribution . In many situations it might be beneficial to include in this prior density cumulative evidence about a parameter from previous scientific studies. This might be obtained by a formal or informal meta-analysis of existing studies. A range of other methods exist to determine or elicit subjective priors (Garthwaite et al., 2005; Gill and Walker, 2005). For example, the histogram method divides the range of into a set of intervals (or ‘bins’) and uses the subjective probability of lying in each interval; from this set of probabilities, may be represented as a discrete prior or converted to a smooth density. Another technique uses prior estimates of moments, for instance in a normal density with prior estimates and of the mean and variance, or prior estimates of summary statistics (median, range) which can be converted to estimates of and (Hozo et al., 2005).

Often, a prior amounts to a form of modelling assumption or hypothesis about the nature of parameters, for example, in random effects models. Thus small area death rate models may include spatially correlated random effects, exchangeable random effects with no spatial pattern, or both. A prior specifying the errors as spatially correlated is likely to be a working model assumption rather than a true cumulation of knowledge.

In many situations, existing knowledge may be difficult to summarise or elicit in the form of an informative prior, and to reflect such essentially prior ignorance, resort is made to non-informative priors. Examples are flat priors (e.g. that a parameter is uniformly distributed between and ) and Jeffreys prior

where is the expected information1 matrix. It is possible that a prior is improper (does not integrate to 1 over its range). Such priors may add to identifiability problems (Gelfand and Sahu, 1999), especially in hierarchical models with random effects intermediate between hyperparameters and data. An alternative strategy is to adopt vague (minimally informative) priors which are ‘just proper’. This strategy is considered below in terms of possible prior densities to adopt for the variance or its inverse. An example for a parameter distributed over all real values might be a normal with mean zero and large variance. To adequately reflect prior ignorance while avoiding impropriety, Spiegelhalter et al. (1996) suggest a prior standard deviation at least an order of magnitude greater than the posterior standard deviation.

1.1.2 Updating information: Prior, likelihood and posterior densities

In classical approaches such as maximum likelihood, inference is based on the likelihood of the data alone. In Bayesian models, the likelihood of the observed data , given a set of parameters , denoted or equivalently , is used to modify the prior beliefs . Updated knowledge based on the observed data and the information contained in the prior densities is summarised in a posterior density, . The relationship between these densities follows from standard probability relations. Thus

and therefore the posterior density can be written

The denominator is a known as the marginal likelihood of the data, and found by integrating the likelihood over the joint prior density

This quantity plays a central role in formal approaches to Bayesian model choice, but for the present purpose can be seen as an unknown proportionality factor, so that

or equivalently

The product is sometimes called the un-normalised posterior density. From the Bayesian perspective, the likelihood is viewed as a function of given fixed data and so elements in the likelihood that are not functions of become part of the proportionality constant in (1.2). Similarly, for a hierarchical model as in (1.1), let denote latent variables depending on hyperparameters . Then one has

or equivalently

Equations (1.2) and (1.3) express mathematically the process whereby updated beliefs are a function of prior knowledge and the sample data evidence.

It is worth introducing at this point the notion of the full conditional density for individual parameters (or parameter blocks) , namely

where denotes the parameter set excluding . These densities are important in MCMC sampling, as discussed below. The full conditional density can be abstracted from the un-normalised posterior density by regarding all terms except those involving as constants.

For example, consider a normal density for observations with likelihood

Assume a gamma prior on , and a prior on . Then the joint posterior density, concatenating constant terms (including the inverse of the marginal likelihood) into the constant , is

The full conditional density for is expressed analytically as

and can be obtained from (1.4) by focusing only on terms that are functions of . Thus

By algebraic re-expression, and with , one may show

Similarly

which can be re-expressed as

where denotes a gamma density with mean and variance .

1.1.3 Predictions and assessment

The principle of updating extends to replicate values or predictions. Before the study a prediction would be based on random draws from the prior density of parameters and is likely to have little precision. Part of the goal of a new study is to use the data as a basis for making improved predictions or evaluation of future options. Thus in a meta-analysis of mortality odds ratios (e.g. for a new as against conventional therapy), it may be useful to assess the likely odds ratio in a hypothetical future study on the basis of findings from existing studies. Such a prediction is based on the likelihood of averaged over the posterior density based on :

where the likelihood of , , usually takes the same...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.6.2014 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics |

| Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics | Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Statistik |

| Mathematik / Informatik ► Mathematik ► Wahrscheinlichkeit / Kombinatorik | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | algorithm • algorithms • Angewandte Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung u. Statistik • Applied Probability & Statistics • APPROACHES • Bayesian • Bayesian analysis • Bayessches Verfahren • Bayes-Verfahren • Biostatistics • Biostatistik • densities • Diagnostics • formal • Hierarchical • hyper population • Introduction • Knowledge • MCMC • metropolishastings • Model Choice • Models • parameters • Prior • References • Software • Statistics • Statistik • Units |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-89506-1 / 1118895061 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-89506-1 / 9781118895061 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich