Adventures of Max Spitzkopf: The Yiddish Sherlock Holmes (eBook)

587 Seiten

White Goat Press (Verlag)

979-8-9909980-6-3 (ISBN)

Mikhl Yashinsky was born in Detroit and graduated with a degree in European history and literature from Harvard. Now living in New York, he works as a teacher and translator; performs in Yiddish theater (singing and acting in Fiddler on the Roof directed by Joel Grey and in the title role of the operetta The Sorceress, both New York Times 'Critic's Pick' productions); and is one of the few people in the world writing original Yiddish plays and musicals. He co-authored the award-winning new Yiddish textbook In eynem (White Goat Press) and is the translator of The Mother of Yiddish Theatre: Memoirs of Ester-Rokhl Kaminska (Bloomsbury).

A rabbi's granddaughter missing, feared murdered . . . a Jew wrong-fully accused of espionage . . . a shtetl teenager kidnapped and sold into prostitution in Turkey . . . in a far corner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, crime is rampant and Jews are at their wit's end. Enter super-sleuth Max Spitzkopf, passionate defender of his people. Brave, ingenious, and a master of disguise, Spitzkopf's crime-solving adventures take him from an Alpine fortress to the sewers of Vienna, and into casinos, brothels, dungeons, and monasteries. Giving a unique twist to a beloved literary genre, the fifteen Spitzkopf mysteries enthralled Yiddish readers over a century ago. Reading these page-turning tales, with their linguistic verve and historical charm masterfully rendered in Mikhl Yashinsky's translation, it's easy to see why the young Isaac Bashevis Singer raced to his Warsaw newsstand to catch each new episode.

Introduction By Mikhl Yashinsky

I present you with a mystery: What would a great writer—the only Nobel laureate of his besieged but unbounded minority language, the son and grandson of rabbis, a fabulist of phantoms and demons, and a sardonic Jeremiah of his destroyed people— read for pleasure as a child? What could possibly be deep and dark enough to fire the imagination of such a boy?

I speak, of course, of Isaac Bashevis Singer. And what was this writer reading as a child under the covers while his father inveighed against the heretical dangers of modernity and his brother began publishing secular literature in the local newspapers? Why, what else but the detective stories of Max Spitzkopf, the “king of detectives, the Viennese Sherlock Holmes”!

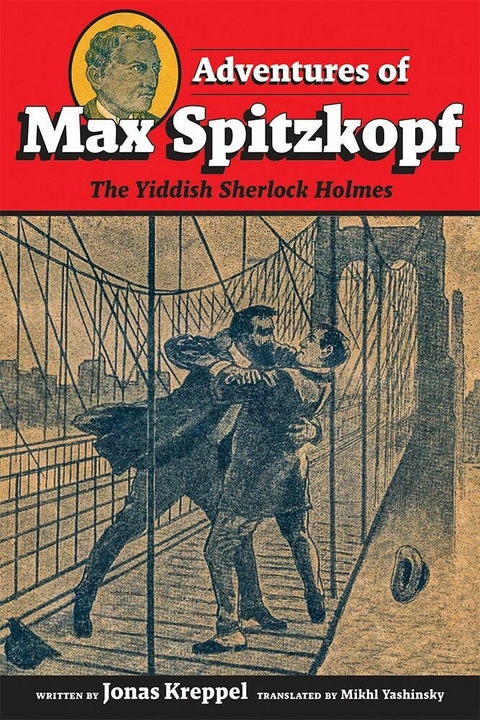

Such were the appellations that accompanied this fictional sleuth’s name on the fifteen pulp-fiction pamphlets that cost only twenty Austrian heller for each shabby little shocker of thirty-two pages, published in Kraków around 1908. Young Isaac Singer wolfed down each volumette like it was nothing more than a dumpling—incidentally, the meaning of their author Jonas Kreppel’s surname. Here is what the Nobel laureate wrote, in his own memoirs, about these fiction feasts of his childhood:

In my eyes, these detective stories were high art. They simply enchanted me. A sentence from one of the booklets remains with me to this very day. It was a caption to an illustration that depicted Max Spitzkopf and his assistant Fuchs surprising a bandit, revolvers in hand. And the detective is calling out, “Halt, you scoundrel! The game is up!”

These naïve words resounded in my ears like heavenly music. I invested them with all of my youthful fantasy.

No Spitzkopf cover exists that adheres perfectly to every detail remembered by Bashevis, a man in his fifties when he set down these memories, but one comes pretty close. Hermann Fuchs, Robin to Spitzkopf’s Batman, does not appear on the cover of “The Smugglers,” but the master detective is there, bearing his usual firearm and the usual defiant expression on his sharp-angled face as he confronts a gang of miscreants with the words “Halt! Shurken!”—“Halt! Scoundrels!”

Pulp can be powerful. A book of fiction need not have the sweep of a thousand-page novel to awe us, and a detective story need not be difficult to figure out in order to surprise us, make us root for the heroes, seethe with hatred for the villains, and wonder if Fuchs will yet again wind up bound in a dungeon somewhere. (Of course he will—and sometimes his hyperintelligent master might, too.) For the mysteries of this supersleuth are not, ultimately, very hard to sleuth out. Often, we do so right along with Spitzkopf, somewhere near the beginning. But how fearlessly he sallies forth into the vortex of danger; how ingeniously he tracks the culprits; how curious his contrivances and costumes; how adorably hapless his assistant; how dastardly the anti-Jewish plots they unravel; how tenderly grateful the victims and their families! It is the colorful settings of wine-and-coffee-soaked Vienna and the faith-immersed shtetl, the lively plotting, the forceful language, the absurdity and slapstick, the vivid and unsubtle characterization, that give these stories their perpetual charm and excitement.

One might not guess that such wildness and derring-do would have emerged from the mind of their stolid creator. In his photograph, the Jewish-Austrian bureaucrat Jonas Kreppel (1874–1940) looks refined and serious, neatly cravatted and mustachioed. But there is a twinkle in his eye and an upward turn to his lips. For all of his serious literary and political accomplishments—and they were many—he also wrote some of the most ludicrous (and ludicrously popular) fiction of his day.

When Kreppel was born on Christmas Day in the shtetl of Drohobych in Austrian Poland, the fourth of seven children, he was called Yoyne by his Hasidic parents, a biblical name meaning “dove.” He played on the reference in one of his many pseudonyms—“La Paloma.” The Spitzkopf stories were issued anonymously, but it was an open secret that they were Kreppel’s handiwork. Perhaps the author left his name off to lend credence to the claim, stated on the back cover of every booklet, that his hero was a real man who “Lives And Breathes” and that “the stories about him are The Absolute Truth.”

This was merely an advertising strategy—there is no evidence that Spitzkopf or his Viennese detective agency, Blitz, actually existed—but it is incontestably true that the crises our hero flew into were nightmarishly prevalent in the reality of European Jewry. The private eye, the back cover goes on to proclaim, “IS A JEW—and he has always taken every opportunity to stand up FOR JEWS.” These Jews in trouble are variously accused of treason against the Austrian state (shades of Alfred Dreyfus) or of blood libel, beset with pogroms, abducted and sold into sexual slavery or sent for forced baptism by Christian clergy, or otherwise ensnared in any number of murderous, rapacious, antisemitic plots.

Tales such as these would have seized the hearts of Yiddish readers, already familiar with them through contemporary newspaper reports and the experiences of neighbors and friends. For them, a hero like Spitzkopf not only nabbed the guilty and freed the innocent but did so with irresistible panache and—perhaps most importantly—in their own language. He would have shone as a beacon of comfort and hope, bright as the rays of his omnipresent elektrishe lampe. And he was such a wiz, a man whose ultra-sharp deduction skills resided in a “pointy head” (the literal meaning of “Spitzkopf”)—that is to say, a decidedly clever mind. The stories of his exploits sold like so many slices of hot strudel. Kreppel became a master at such fare, derided as shund—lowbrow trash—in the more rarefied echelons of Yiddish literature but adored by the eagerly reading masses.

Writing Spitzkopf stories was hardly Kreppel’s sole endeavor. After marrying Helene Fischer, the daughter of Kraków publisher Josef Fischer, Kreppel put his training as a printer and typesetter to good use when he took over the management of his father-in-law’s popular fiction business, the Jüdischer Roman-Verlag (Jewish Novel Publishing House). For both that firm and, a couple decades later, in the 1920s, that of publisher Symcha Freund in the Polish city of Przemyśl, Kreppel penned dozens of the slim-format page-turners that Spitzkopf helped popularize—crime capers, biblical and Hasidic legends, supposedly firsthand accounts of the First World War and of Jews who met Napoleon. Nor was Kreppel’s engagement with the personalities and predicaments of his people limited to storybooks. His longest work was in German and amounts to 891 scrupulously researched pages on Juden und Judentum von Heute (Jews and Judaism of Today), published in Zürich and Vienna in 1925. Even Yoel Teitelbaum, the august founder of the strict Satmar Hasidic sect, had to be impressed by Kreppel’s success. Upon encountering the “tall, lanky” man as a youth around the close of the nineteenth century and being regaled by him with one of his homespun yarns, the name Kreppel stuck in the “dumpling” of Teitelbaum’s mind, as he put it. Eventually, he started seeing that unforgettable moniker pop up on newsstands everywhere. The man’s books, Teitelbaum later wrote, were “being sold and distributed far and wide as though they were Holy Writ. A terrible and terrifying thing.”

In 1915, after a successful publishing career in Kraków and Lviv and after serving as a delegate to the famous 1908 “Conference for the Yiddish Language” in Czernowitz, Kreppel moved to Vienna, the royal and imperial capital that had so fired his fancy in the Spitzkopf tales. There he embarked on the second of his grand careers, one fairly unusual for a Yiddish man of letters: serving Austria, of which he was an avowed patriot, as a government press officer, first in the Austrian Foreign Ministry during the waning days of the Habsburg Empire and then, from 1924, in the Federal Chancellery of the Austrian Republic. Setting up shop at his favored Café Arkaden, he gradually gained the approbation of his colleagues and co-religionists. He was a Viennese gentleman at last, one whose suavity and skill matched those of his most famous protagonist. In his adopted city Kreppel edited the German-language journal Jüdische Korrespondenz, the organ of the Orthodox Jewish political movement known as the Agudas Yisroel. His twin allegiances, to his people and his patria, are reflected in the title of the only biography dedicated to his life, published in Vienna in 2017: Jonas Kreppel—Glaubenstreu und Vaterländisch (“true to his faith and his fatherland”).

But when that fatherland turned on him, such fidelity was for naught. As Hitler consolidated power, Kreppel published a pamphlet alerting the German-reading public to the peril of the dictator’s expansionist plans and criticizing the appeasement policies that weakly hoped to restrain him. He titled it with his usual flair: 1935—das Shicksalsjahr Europas (Europe’s Fateful Year). In May 1938, seven weeks after Austria welcomed Nazi annexation, Kreppel was rounded up along with other...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.12.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-9909980-6-3 / 9798990998063 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,4 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich