Mercy of Others (eBook)

227 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3178-1870-8 (ISBN)

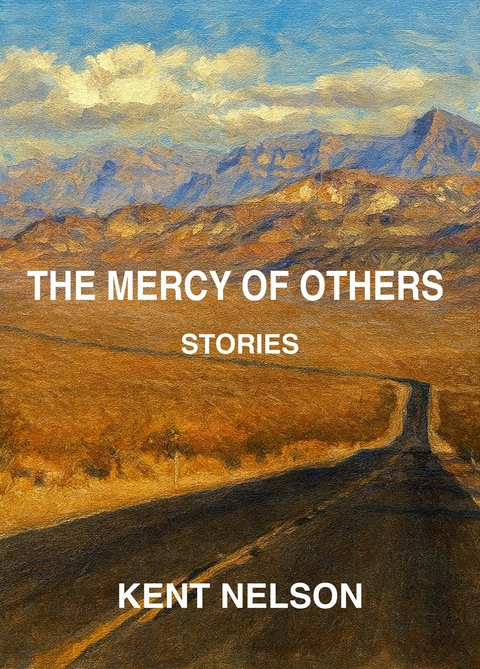

Kent Nelson is a prolific author who has published twelve books of fiction and over one hundred and sixty stories. His stories have been included in the Pushcart and O. Henry anthologies, as well multiple times within The Best American Stories series, while his books have been awarded numerous accolades including the Edward Abbey Prize for Eco-fiction, the Colorado Book Award, and the Mountain and Plains Booksellers award for best novel. Kent has been a life-long birder, and searching for rare species has led him to every part of North America, including Attu-the last Aleutian Island-as well as to Costa Rica, Ecuador, Uruguay, Bhutan, New Zealand, and Australia. He has a life list of 771 species in North America and 890 in Ecuador. In college, Kent was a varsity athlete in tennis and ice hockey. He later played professional tennis in Europe and was once ranked sixth in North America in 45+ squash. He has run the Pikes Peak Marathon twice, 26.2 miles and 7814 feet up and down. Kent lives in Ouray, Colorado.

In Death Valley, a man picks up a Dutch woman hitchhiker, and things go from bad to worse. A father in South Carolina receives a goodbye call from his daughter, prompting him to fly to New Mexico to look for her. A couple from Minnesota with a sordid past spend the winter in an RV park in Texas. A truant kid and his girlfriend in Nebraska find a moose that's wandered into the state. A Black woman in Florida who goes to live on her father's abandoned farm discovers a White woman has been staying there. In this compelling collection of heart-wrenching stories, narrators of disparate ages and backgrounds grapple with odd and unexpected circumstances that awaken understanding and self-discovery. Readers who appreciate beautiful and meaningful prose will savor The Mercy of Others.

PUBLIC TROUBLE

We should have been more alert, all of us, more aware. Those closer to the circumstances, like Ivo Darius and his wife, Frieda, might have figured out something was wrong, but they were busy feeding cattle and had used the down time in winter to build an aluminum storage shed. The dental hygienist, Sara Warren, who also lived out there, could have said more, but why would she? Of course Emily Jefferson’s silence was understandable, but she didn’t enter the picture until later, when it was too late to change the course of events. We have all pointed at social services, but they can’t be involved until someone comes forward, unless there’s public trouble—malnourishment, truancy from school, a suspicious bruise. And there wasn’t. But even with full knowledge in advance, could we have done anything? Even if all of us together had been vigilant of the signs, even if someone had spoken up, could we have prevented it from happening?

Everyone knew the Olshanskys. The father, Del, worked part-time at the loading dock at Walmart, and we often saw him in town at the Silver Nugget on Main Street or on the town’s embarrassing highway strip at the bowling alley, or Taco Bell, or the Branding Iron. He was a handsome man—dark eyes, a strong nose, chin and jaw unshaven, the way movie stars appear these days. If he’d cared at all for appearances, he might have been called dashing. He looked like the sort who’d lose his temper and get into bar fights, but no, he was calm, off-hand, halfway pleasant, no matter what he’d had to drink. His appearance was rough—his jeans had holes in the knees, and his shirts were torn—and he didn’t have much ambition. That isn’t a crime. The sheriff, all of us in town, had seen a lot of men worse than Del, lots of couples worse than Del and Billie Jean.

The Olshanskys lived out past the landfill in the piñon-juniper foothills where there wasn't much water. They had dug a well and watered a patch of grass bordered by rocks worn smooth by the river. There was an Elcar-fenced pen for a dog, too, though when we were there—in the winter, when this all happened—there wasn’t a dog. The house was really a trailer they’d added on to. In front they'd built a porch with a green plastic snowshed roof slanting to one side, and a façade of cinder blocks to hide the cheap vinyl siding. In back, they’d cobbled on two bedrooms with views of the Sangre de Cristos. Billie Jean was a nurse’s assistant at the hospital, just a hundred beds, but apparently she had time for a garden because there was a raised bed inside railroad ties and hauled-in topsoil. We don't know what she grew because, when we saw it, the plants were black and draped in snow.

Most of us don't blame Del and Billie Jean. We think it started at that school, though who knows whether a beginning to such a thing can be deciphered. Even if it didn’t start at the school, the place was a catalyst. It had to be. Before that, for the first several years they were around, the Olshansky kids had gone to the public school. They lived in town most of that time, and even for two years after they moved to the trailer, the kids took the school bus in. Danielle, the oldest, was Billie Jean’s daughter from a former marriage. She was a smart kid, and one of the English teachers, Mary Padua, thought Danielle had photographic memory because she recited “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” and often wrote answers on exams in the exact same words that were in the texts. If she’d wanted to, she could have gone to college, but college wasn't an ambition for most high school students here, and after graduation she moved upriver to Nathrop and worked as a scheduler for raft trips.

Six years younger was Marya, Del's first. She was the athlete. A lot of us had kids in school, and all through junior high and high school we saw Marya play basketball. She was not just good, she was great. She leaped higher than any other girl we’d seen, and her jump shot floated to the basket. She was pretty, too, tall and lithe, and ambitious. Often, when we delivered our children to school in the mornings, Marya had ridden her bike six miles in from the trailer and was at the playground shooting baskets.

The youngest was Carlos, two grades behind Marya. No one understood naming a child Carlos when he wasn't Latino, but, as someone said, it's no different from naming a child Danielle and Kurt. The thing about Carlos was—how do you say it about a boy?—he was easy to look at. He had long blond hair, high cheekbones, a perfect nose. His eyes were deep set, shadowed, and such a pale shade of blue that when you saw them in a certain light, they reminded you of sky. Many of us, when we first laid eyes on him, said, “There is the most beautiful boy in the world.”

During the school year we heard about Carlos every day. Our children came home saying Carlos this, Carlos that, how good he was at sports, how pretty he was. When he walked by in the hall, apparently everyone, all grades, boys and girls both, stopped whatever they were doing and watched him pass.

He wasn't a big kid, but he played halfback and ran track, and he was a good student, all As. The girls loved him, and the boys admired him, too, though they were all a little afraid of him because of his beauty. He wasn’t one of them.

“He doesn’t choose one girl.” That’s what all our kids said. That’s what the parents heard. “He likes everybody,” they said. Or, “He barely talks. We can’t tell what girl he likes.”

“What would you like him to say?” we asked.

The kids didn't know what Carlos should say. Silence was power. It made them uneasy he was so quiet. He went days without saying anything. He wouldn’t even answer questions in class.

The Olshanskys came from up north, Wyoming or Montana, no one knew for sure. Del was pretty vague on the subject. When we first knew them, they lived on River Street, right downtown, six blocks from the water, in a rented house barely big enough for a couple, let alone a family. At that time, Del did home repair, mowed lawns, worked freelance as an auto mechanic. We all gave him work. When Fred Larsen put a garage on his split-level, he hired Del for the crew, and when Jerry Matuzcek's Blazer broke down, he paid Del to fix it. Del was quiet, but personable, and talked if he was spoken to. They lived in that house on River Street for several years, and there was never any trouble. Nedda Saenz owned the house, and she said they were late every month with the rent, but eventually they got the money to her. “I don’t know why it wasn’t on the first,” Nedda said, “but at least they paid.”

They weren't first-of-the-month people. They had a way about them that made people unsure. They looked unreliable. Billie Jean, for instance, never looked right at you when she spoke, and she was frequently late to work at the hospital. Once there was a dispute about some missing money. Everyone thought she'd taken it—she never denied it—but it was later proved to be a clerical error. Why wouldn't she have said she was not guilty? And though Del never had enough money for new clothes, he had enough to buy beer. They never saved for another car, or a newer used one, but Del managed to keep their '81 Dodge truck running, even if it wasn't the most efficient vehicle. They weren't shiftless, exactly, but no one would have been surprised if, one day, the whole family was up and gone. We thought of them as about to disappear.

At first we admired them, reluctantly perhaps, for buying the trailer and settling in. At the same time, it was foolish because the land was glacial moraine, and they had to put in a deep well. They had payments to make every month on the land, and, in general, it cost more to live out of town. Telephone and trash pick up was more expensive; appliance repairmen and plumbers charged mileage; Billie Jean had to drive farther to work. And you're isolated—that's a hidden cost. If you needed help, neighbors weren’t close by.

For a few years there, we in town were less attentive to them. Ivo and Frieda Darius and Luther and Sara Warren lived farther west up the gravel road where the creek came out of the mountains, and they saw the Olshanskys more often than anyone else. Sara worked in a dentist’s office, and she drove by every morning. She frequently saw the Olshansky kids at the bus stop—the three of them standing alone on the highway. In warmer weather, coming home late in the day, she sometimes saw Del working on the façade of the trailer or Billie Jean digging in the garden. Ivo Darius was older, a rancher, and was frequently laid up with real or imaginary illnesses. He said he’d heard gunshots a few times—target practice, he assumed—out in the arroyo. There was nothing unusual about that. Ivo owned two rifles himself and sometimes shot marauding skunks or coyotes.

The only occasion anyone had close contact with one of the Olshanskys was on a spring morning when Sara Warren saw Carlos running to the bus stop. Carlos was twelve or thirteen then, and the Olshanskys had lived in the trailer more than a year. At the bottom of the hill, the bus was pulling away, and Carlos accepted a lift to school. Sara asked the predictable general questions—how was school? How do you like living out here? What are you doing this summer? But Carlos made no reply beyond a few guttural sounds. Carlos stared straight out the windshield as if he were fixated or drugged, or so focused inward he hadn't heard the questions. Sara said later she wasn’t sure Carlos could speak. Sara remembered that particular morning because an eagle had dived down right next to the gravel road into the piñons and killed a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.11.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3178-1870-8 / 9798317818708 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich