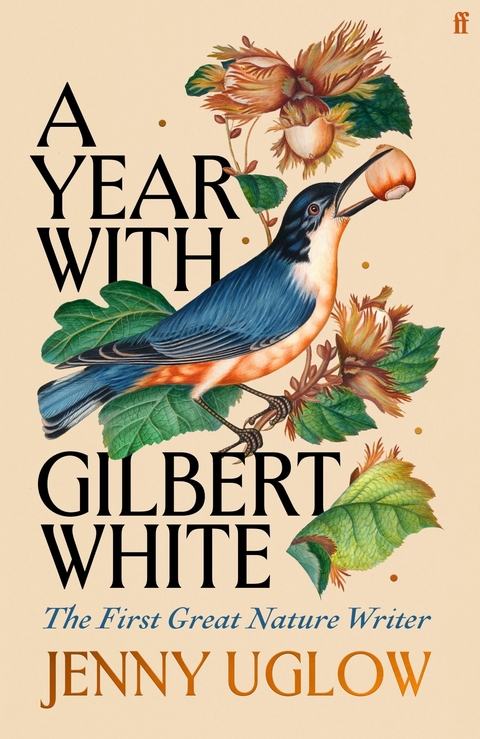

Year with Gilbert White (eBook)

416 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-35420-7 (ISBN)

Jenny Uglow writes on literature, art, and social history. Her books include award-winning biographies on Elizabeth Gaskell and George Eliot, William Hogarth, Thomas Bewick and Edward Lear, as well as group studies including The Lunar Men and the panoramic In These Times. A retired editorial director of Chatto & Windus, and former Chair of the Council of the Royal Society of Literature, she grew up in Cumbria, and she and her husband Steve now live in Borrowdale.

'Uglow makes us feel the life beyond the facts.' GUARDIAN'Few can match Uglow's skill at conjuring up a scene, or illuminating a character.' SUNDAY TIMES'Charming . . . Like Radio 4's shipping forecast for naturalists.' Andrea Wulf, FINANCIAL TIMES'A glorious celebration of curiosity and nature.'OBSERVERA BOOK OF THE YEAR IN THE TIMES, THE SPECTATOR, FINANCIAL TIMES, OBSERVER AND NEW STATESMANIn 1781, Gilbert White was a country curate, living in the Hampshire village he had known all his life. Fascinated by the fauna, flora and people around him, he kept journals for many years, and, at that time, was halfway to completing his path-breaking The Natural History of Selborne. No one had written like this before, with such close observation, humour, and sympathy: his spellbinding book has remained in print ever since, treasured by generations of readers. Jenny Uglow illuminates this quirky, warm-hearted man, 'the father of ecology', by following a single year in his Naturalist's Journal. As his diary jumps from topic to topic, she accompanies Gilbert from frost to summer drought, from the migration of birds to the sex lives of snails and the coming of harvest. Fresh, alive and original - and packed with rich colour illustrations - A Year with Gilbert White invites us to see the natural world anew, with astonishment and wonder. 'A feast of a book, it is beautifully illustrated and compulsively readable.'LITERARY REVIEW'The author brings her subject endearingly alive . . . [an] enriching book.' NATURE

In 1781, the year this book spends with Gilbert White, he was sixty, a country curate in Hampshire, comfortably off but not rich, living in a village he had known all his life, surrounded by friends and constantly in touch with his family. All that remained to complete his satisfaction, as Jane Austen might say, was the publication of his book, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. He had planned and worked on this for the past seven years and would spend a further seven polishing and revising it, so 1781 was the midpoint in its long gestation. But in fact the year could have been picked out with a pin, a typical year in the life of a man who was watching the natural world and the goings-on of his village, while slowly creating a wholly remarkable work.

The main part of Gilbert White’s book is a personal evocation of the birds, insects and other animals in a single parish, and of the people who lived there. The second part, about the parish history – the ‘Antiquities’ of its title – is often dropped from later editions, so it appears simply as The Natural History of Selborne. ‘Scientific’ in its detail, it is also intimate and informal in tone, open to speculation and amazement. No naturalist – or ‘natural philosopher’, as they were then called – had written like this before, with a vivid, flowing style that brings out the author’s own enquiring, warm personality, as well as his loving record of the life around him. This is what has made The Natural History a treasured work, never out of print since it was first published in 1789, a book that nineteenth-century emigrants and soldiers fighting in the trenches of World War I took with them as a vision of the country they had left behind, an emblem of ‘home’.

The book’s core is made up of two sequences of letters that White wrote to his fellow naturalists Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington. He kept copies of these letters, and over time he played with them and edited them, putting in new details and stories, and finally adding extra, invented ‘letters’, which were never sent, to give a frame for the whole.1 Letters are by their very nature open-ended, occasional and immediate, and this structure allowed him to jump from topic to topic, so that readers could follow him as he roamed through a wood or dissected a bird, sharing his feelings as he watched an owl swoop or recoiled from a foul-smelling bat, or pondered the reproduction of eels and chats about hops and hay.

As he worked, he turned constantly to the journals that he had kept for many years, using them to compare dates, to chart the slight variations in the flowering-time of wildflowers or the arrival of migrating birds. He mined his journals, too, for striking examples and incidents, like the nuthatch wedging nuts in a gate or the adder shedding its skin like a glove. The journals let him keep his finger on the pulse of the year, recording the small things that sum up a day. His jottings were quick, shorn of adjectives, curious, cross, delighted, awestruck, sharp as his watching eye.

*

Wrens scuttling under hedges, mist across fields, owls chasing swallows nesting in chimneys and falling down in clouds of soot – Gilbert White made these come alive for me when I picked up The Natural History of Selborne in my teens. The bald opening worked like a children’s book, telling you exactly where you were:

The parish of Selborne lies in the extreme eastern corner of the county of Hampshire,2 bordering on the county of Sussex, and not far from the county of Surrey; is about fifty miles south-west of London, in latitude 51, and near midway between the towns of Alton and Petersfield.

I liked the way he circled above the map like a hawk, before swooping down to the village street, to birds in the bushes and crickets in the grass. I liked the letter form, with its vivid digressions (‘first I must mention,3 as a great curiosity …’), turning blithely from ancient oaks to stubborn ravens and unearthed fossils. Back then, I didn’t read all of The Natural History, dense with detail, or appreciate White’s discoveries and arguments. He sprang into focus as a man and a naturalist when I read Richard Mabey’s biography, first published in 1986 (a perfect life, as far as I’m concerned). I then became intrigued as to how he fitted into the interest in natural history that blossomed from the mid-eighteenth to the early nineteenth century. This was shared among all classes, from Midlands industrialists collecting minerals and fossils to Thomas Bewick in Northumberland engraving birds; from women botanists dissecting bulbs to the workers of Manchester a generation later in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton, ‘who know the name and habitat of every plant within a day’s walk from their dwellings’.4

That spreading interest was something different and democratic. It drew on scholarly studies, but it was born from people’s contact with the natural world in the course of their daily lives. Its beginnings coincided with the vogue for the ‘picturesque’, which was not only an appreciation of landscape as a picture, but a valuing of an emotional response, the ability to admire, to be delighted or moved by the odd and the irregular, to see a familiar landscape in a new, personal way. A copse was no longer an economic fact – ‘a fine stand of timber’ – but a reminder of home, or of lost love, or of a sense of place so intense that the felling of an oak or a line of poplars could feel like a personal grief.

I wanted to understand this new kind of writing, which is imbued with such feeling and links scholarly knowledge to simple daily watching. It seemed to demand a new way of approaching Gilbert White. Was it possible, I wondered, to follow him through the year, writing day by day myself, alongside his Naturalist’s Journal?

The overarching narrative is the passing of the year, in which each month has its distinctive character. Following a journal, however, means surrendering continuity to serendipity, abandoning a straightforward account and accepting the wayward and random. The sequence may jump from poetry to potatoes, from sermons to swifts. Some days in 1781, Gilbert – I call him by his first name because there are so many Whites in his spreading family – has nothing to report except the weather. This lets me look at entries from other years, following the track of his life, forward and back and sideways, exploring the way that his thinking was coloured by his experience and milieu and the ideas of his time. It’s like meeting someone in late middle age, learning about them not in a chronological stream, but bit by bit, at first in a rush, then in sporadic bursts. Our lives are linear, running on through the years, but they are also layered, like strata, or a tangled hedgerow, where branches, fed by unseen roots, shelter an abundance of life.

*

In the century after Gilbert White died, his admirers developed an image of him as an unworldly clergyman exploring some pre-industrial idyll. To the American writer James Russell Lowell, he seemed ‘to have lived before the Fall … his volumes are the journal of Adam in Paradise’.5 Yet Selborne was no lost Eden and Gilbert no solitary idealist. In many ways he was typical of clergy families and country gentlefolk: classically educated, generous to the poor but complacently sure of his place and proud of his country. In 1781, the year of this journal, George III had been on the throne for twenty-one years, with no serious sign yet of his later madness. For most of that time, from the end of war with France in 1763 until the start of the American War of Independence in 1776, Britain basked in its dominance in Europe, and in its booming trade and ‘polite’ culture. Canals and new turnpikes criss-crossed the land, and huge, improved steam engines thumped in foundries and mines; soon steam would replace water power in mills and new ‘manufactories’. In the cities, theatres, pleasure gardens and coffee houses flourished. In small towns like Alton, three miles from Selborne, the doctors and lawyers, corn merchants and brewers and their families flocked to assemblies and balls, ordered new novels and set off for musical evenings and whist parties, the men brushing their wigs, and the women trying out new fashions.

The dominant note was the rise in prosperity of the ‘middling classes’, but such generalisations quickly crumble, as they do in any age. We have to set Gainsborough beauties against boys hung at Tyburn; tea caddies on the table against bloodshed in India; sugar cones in the larder against slave ships at sea. Squires enclosed the land, while homeless vagrants roamed the roads. A London toff could lose £20,000 in one night at cards, while a farm labourer earned 1s 6d a day. There were increasingly fierce demands for democratic rights. Amid all this, thinkers in Britain and America, and the rational philosophes in France, argued about society and politics, about...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.9.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-35420-3 / 0571354203 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-35420-7 / 9780571354207 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich