Navigating Cancer From Both Sides (eBook)

200 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3178-0624-8 (ISBN)

Deborah Robinson Bailey RN, BS, BSN, MSN is a retired nurse executive, professor, healthcare lobbyist, and two-time cancer survivor whose career has spanned nearly five decades. She served as Vice President of Nursing and later Executive Director of Governmental Affairs at a large healthcare system, where she played a key role in shaping public health policy, securing millions in healthcare funding, and advancing patient advocacy across Georgia. Deb's diverse experience includes psychiatric nursing, academic teaching, international consulting, and co-authoring award-winning psychiatric nursing textbooks. She has been appointed by three Georgia governors to multiple state healthcare boards, and has received numerous honors including the Inaugural Georgia Alliance of Community Hospitals' 'Healthcare Woman of the Year.' Also an accomplished artist and published writer, Deb blends clinical expertise with lived experience in her work-advocating for compassionate, informed, and empowered care.

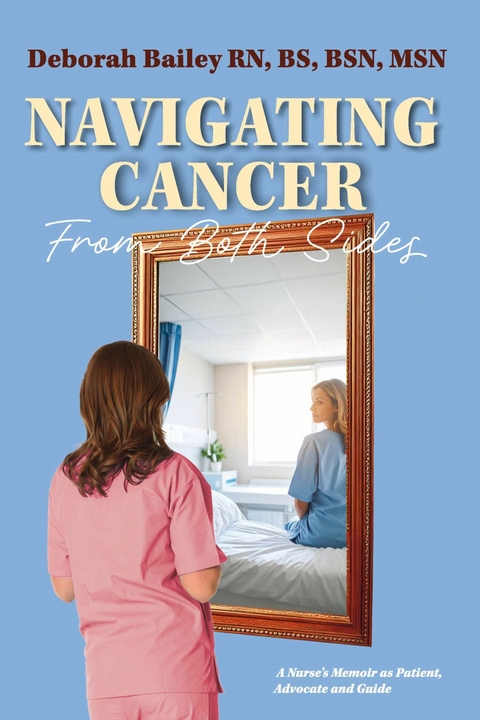

Navigating Cancer from Both Sides: A Nurse's Memoir as Patient, Advocate, and GuideWhen a nurse becomes the patient, the journey changes but the calling to heal remains. Deb Bailey was a marathon runner, a vegan, a non-drinker, and a lifelong healthcare professional. So when she was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40, she did what few expected: she chose surgery, but walked away from chemotherapy and radiation turning instead to alternative therapies, deep inner work, and fierce self-advocacy. Thirty years later, a second diagnosis this time of head and neck cancer brought her back into the fight, once again navigating fear, medicine, and healing in a system she thought she knew. Part memoir, part guidebook, Navigating Cancer from Both Sides weaves personal story, professional insight, and spiritual wisdom into a powerful invitation: to ask questions, trust your instincts, and reclaim your voice in the face of illness. With over 40 years as a nurse, professor, healthcare executive, and lobbyist, Deb offers readers a rare glimpse behind the curtain of modern medicine revealing both its strengths and its blind spots. This is not a one-size-fits-all survival story. It's an honest, hopeful roadmap for patients, caregivers, and anyone seeking to walk their own healing path with clarity and courage.

Chapter 1

Becoming the Nurse I Will Someday Need

I am standing in front of an audience of over three hundred professional healthcare workers, doctors, and elected members of the Georgia House of Representatives and Georgia State Senators. I am the recipient of the inaugural Healthcare Woman of the Year award for the State of Georgia.

I have worked hard to be a respected nurse leader and a constant professional, but I am more than what they see. Unknown to the audience, this award recipient has navigated a complex and personal journey through the very system she has spent her career improving. They see the accolades, the titles, the years of dedication to nursing, leadership, education, and advocacy. What they don’t see is the battle that began decades ago when, at just forty years old, I found myself not as a nurse caring for a patient, but as the patient myself—diagnosed with breast cancer.

As I stand at the podium, my mind flashes back to the younger version of myself—the eager nursing student, the determined young woman who entered healthcare with a mission to heal and serve. I never imagined that one day, I would have to use every ounce of knowledge, experience, and resilience to navigate my own care and to fight for my own survival.

My journey into nursing wasn’t just a career choice—it was a calling. But it wasn’t a calling I heard. It was a calling my mother said she heard for me; and in those early years, I followed it to please her. Much of my life back then revolved around seeking her approval, but that is a story for another time.

My parents grew up during the Great Depression, and they carried with them the weight of that era’s lessons. Hard work wasn’t just a virtue—it was a necessity. And they believed their five children should understand that as well. By the time I was eight, I was cutting grass and digging flower beds for wealthy neighbors. But at 14, my mother secured a job for me in the office, on weekends, at the nursing home where she worked as a nursing assistant.

The nursing home was a world unto itself—a 100-bed facility where I saw the extremes of human behavior. There was kindness—moments of quiet tenderness as caregivers comforted patients, their hands gentle and compassionate. But there was cruelty, too, and it left a mark on me that I would carry into my nursing career. Because of my age, I wasn’t really allowed to provide hands-on care, so I worked in the office, collecting payments from families who could barely afford to keep their loved ones there. I felt the weight of their struggles, but nothing could prepare me for what I witnessed behind the scenes.

The nursing home was run by the owner/administrator, a man who was almost a walking caricature. He was a large, cigar-chomping figure—the type you might expect to see in a film depicting greed and corruption. I watched him preside over the kitchen, watching the staff grind bologna to serve as the day’s meat, all in the name of saving a few extra dollars. His focus wasn’t on the well-being of the patients—it was on turning a profit.

I remember one moment with tremendous clarity: I watched him strike a patient. The injustice of it burned into me, sparking a quiet but growing determination that one day, I would do things differently. A few years later, perhaps driven by his own guilt, he ended his life, driving his expensive car off a bridge at a nearby lake.

I don’t know why some people burn with outrage at injustice. Perhaps I was always that way, but in that moment, my own powerlessness seared into me, shaping everything that would follow. That experience planted the seed of my purpose—one rooted not only in compassion and in the belief that every patient deserves kindness and dignity, but in an unshakable resolve to grow, to gain the knowledge and power that would ensure I could do more than just bear witness—I could act with agency.

Each day, I would take my lunch break out of the office to help the staff feed lunch to the patients who were not able to do this for themselves. Maybe it was during this time that I decided that I might, if I were a nurse, be able to make a difference in someone’s life. After working at the nursing home every weekend throughout high school, I decided to attend nursing school. I mentioned earlier that my mother was a nursing assistant; she only had a tenth-grade education. She left school to work behind the makeup counter at a Woolworths, but only for a short time, as she subsequently would become a “Rosie the Riveter,” making shells and bombs for the soldiers in World War II. She did not know at that time that one of those soldiers would one day become her husband, a soldier who had endured being a prisoner of war. He had escaped into the mountains of the Dolomites in Italy during the winter. He’d finally found his way back across enemy lines, but only after the army had told his family that he was dead. After finding his way back home, he and my mom married. His wartime experiences caused trauma that would last throughout his lifetime. They call it PTSD now, but earlier it didn’t really have a name. Sometimes, as with my dad, it was given another name: alcoholism.

He was the kindest soul that ever walked this earth, and it made sense to us, even as children, that he would have to drink to soothe his soul from what he had done and what he had seen. His demons would remain a mystery to his five children. Regardless of the suffering they endured during the war, his generation did not speak about the suffering they experienced, which plagued them for a lifetime.

It was with this upbringing that I left high school totally unprepared (from an education standpoint) for nursing school. I did many things to please my mom, but it wasn’t just my mother that I tried to please. I was born with something in me that made me do many things that I didn’t really want to do to try and make others happy, trying to make them like me. So, during high school, making people like me seemed much more important than learning. When I went to my first interview for admittance into nursing school, they told me I was not prepared. They were right. Later, I would also learn that my people-pleasing tendency is a common personality characteristic of women who develop breast cancer later in life.

Honestly, I should have known that I wasn’t prepared, but I thought if they liked me, they would admit me to nursing school. Then I met Mrs. Evelyn Waugh, and she was clear that I wasn’t going to be accepted into the nursing program. She had exceptionally high standards for her students, and her school had a 100 percent success rate on the National Nursing Board Exams. She wasn’t about to let someone like me ruin that record. If I even wanted to be considered for the upcoming class, I would first need to attend summer school, take organic and inorganic chemistry in a college environment, and, further, make As. Then I would be accepted provisionally into nursing school. I had made Cs in chemistry in high school. I’m not sure what I was thinking that I could somehow go to college and make As, but there is something about being told “no” that motivates me. I applied myself, and in the fall of 1971, I became a nursing student. Little did I realize at that time that Mrs. Waugh, as I continued to call her the rest of her life, would become one of my most cherished best friends and a professional mentor for the rest of my career.

It was also that fall that my mother, with her tenth-grade education, got her GED, and we entered nursing school on the same day. She would go to LPN School, and I would attend an RN program. We were so proud of her, and I would come home from school most weekends to help her with her classes. Learning to do the equations and the dosages was especially hard for her, but she was determined to be better equipped to influence the care she had witnessed and been permitted to provide. Becoming a nurse was not easy; the education was rigorous, the training grueling, and the first years in the profession were nothing short of baptism by fire. The long shifts, the emotional toll of patient care, the constant learning—all of it shaped me into the nurse I would become.

There was so much about nursing school that I really did not like, but I was determined by that point, and I succeeded, receiving the medical-surgical nursing awards, becoming the president of my senior class, and excelling in every way. What stood out to me most in nursing school wasn’t the medical-surgical rotations—honestly, I didn’t enjoy that part. What truly drew me in was psychiatric nursing. I still remember walking into the state psychiatric hospital and hearing the door lock behind me. In that moment, I felt a deep sense of compassion—more than I had ever felt for patients in other settings. There was a stark difference in how these individuals were treated. While patients with physical illnesses were often met with understanding and care, those with mental illness faced stigma and a noticeable lack of empathy. It struck me as a profound injustice that seemed widely accepted in the field. Even back then, I knew that mental illness was a disease like any other, even if that wasn’t the prevailing view. The absence of kindness in their care is part of what drew me to psychiatry—it felt like a place where compassion was most urgently needed. Upon graduation, I started working on a psychiatric unit that also served as a drug rehab unit. I can still remember my faculty disparaging my choice and telling me I was going to be a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.7.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3178-0624-8 / 9798317806248 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 641 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich