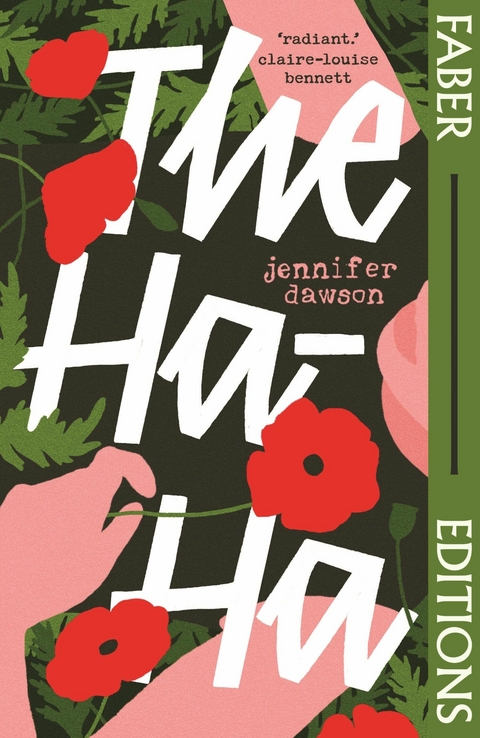

Ha-Ha (Faber Editions) (eBook)

252 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-39026-7 (ISBN)

Jennifer Dawson (1929 - 2000) was born and brought up in Kennington and Camberwell with her three sisters and one brother in a family of Fabian socialists; her mother was a journalist and her father worked for the Workers' Travel Association. She read History at St Anne's College, Oxford, where she suffered a breakdown and spent several months in the local hospital. After graduating in 1954, Dawson worked variously as a teacher in a convent in France; a dictionary subeditor and indexer for the Clarendon Press and Oxford University Press; a welfare worker in London's East End; and a social worker in a psychiatric hospital. Her experience both as a mental health professional and as a patient formed the basis for her acclaimed 1961 debut novel The Ha-Ha, which won that year's James Tait Black Memorial Prize as well as being adapted for the stage and broadcast by the BBC on radio and television. In 1959 she was awarded the Dawes Hicks Scholarship for Philosophy to study at University College London. Dawson was committed to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament from its inception and met her husband, Michael Hinton - an Oxford philosophy don - during the 1963 Aldermaston march. They lived for many years in Charlbury in Oxfordshire, where she remained active in the peace movement. Over her lifetime Dawson wrote six more novels, a collection of short stories, and co-authored a children's adventure story. She died in 2000.

This lost coming-of-age classic is a tragicomic portrait of one young woman's university breakdown and recovery for fans of The Bell Jar and Girl, Interrupted. 'More relevant than ever.' Daisy Johnson (in a new foreword)'It took my breath away.' Meg Mason'A magnificent literary experience.' Melissa Broder'Enthralling and necessary.' Claire Kilroy'Radiant and powerful.' Claire-Louise BennettI wanted the knack of existing. I did not know the rules ... A tea party at an Oxford college. Earnest undergraduates in floral dresses clink cups, discussing essay-crises, punting, summer balls. But to one student, they are grotesquely transformed: she is sitting among ominous armadillos with scaly shells, buzzing with black flies. Then, the laughter comes. As she is engulfed by mirthless hysterics, the Principal has no choice but to send her away. Josephine's entrance into the world of other people wasn't what she imagined. Since her mother's death, reality seems a badly painted canvas, viewed through the wrong end of a telescope; she always thinks the wrong things, cowed by the brightness of existence. It is a relief to belong, for once, within the mental institution where she is taken. But eventually, she must reintegrate with society-and through a transformative encounter with a fellow patient, a return to real life seems possible ... Winner of the 1961 James Tait Black Memorial Prize

‘they were all very kind at Oxford,’ I assured her, for she had seemed to think they were not. ‘No one shunned me or ripped my stockings or took my bicycle on “loan”.’

‘So,’ said the Sister nodding as she slid the enormous bundle of silver keys into her pocket. ‘So. That was good.’

She smiled and waited for me to go on. She was a German, I thought. Her voice moved up and down so, and her ‘r’s were so rich and long in her throat.

‘So.’ It seemed the right occasion, that first day, to go on. ‘So you see, I could not have been unhappy there. In fact I had no enemies at all. The other students were all very friendly and pleasant, and used to wave as they passed and cry: “How goes it?” or “Press on regardless”. Most encouraging. But in fact I never needed any encouragement. My favourite hymn had always been “Glad that I live am I”, to which Mother could add an excellent little alto part.’

‘Really. Is that so?’ the Sister nodded again, folding her starched apron carefully up in front of her and sitting down on the wireworks of the bed. I had not had time to make it up yet. ‘May I? May I make myself at home? So. That was good.’

She had only just come in and introduced herself as the ward-sister, and I had only just moved up here, to the second floor, to the ‘side-rooms’, as they were called, from the other ward that was always full and noisy. The room was very small, like a cupboard, with an iron bedstead down one half, and a wicker chair and a door on the other. It was a change of view I had only just been given, and when the Sister folded up her apron and sat down, I saw that the room was now mine, and that she wanted to talk.

‘So, that was good,’ she was repeating. She leaned back against the bed-end and stared at me. She was small and dark, but her eyes were large, and so full of a devouring emotion that I thought she might swallow me. ‘The intellectual, academic world must have been a very great experience. In Germany we call it studenten …’

But I have forgotten now what she said they called it. For that was a year ago and my mind was full of other things then, surprise and expectations.

It was true though that Oxford had been a very great experience. You see, in my adolescence and at school I had never really been au fait. I used to get into trouble for thinking of the wrong things and letting them loose verbally, and as no one ever told me what the right ones were, I was in the dark most of the time. But at the University, I discovered, there was no rule of this kind. You were allowed to think of what you liked, without any hindrance.

The Sister leaned over and searched my face with her yearning eyes. ‘So,’ she cried, ‘I see that you made some good friends at that very famous chair of learning? You …’ she fumbled for the word, ‘you …’

While she searched for the word I climbed over the bed on to the window-sill to see what it was like – this new world that I had just been given. It was evening. From the ward beneath came that prolonged, even and rhythmic clapping that I was so familiar with. I could picture her so well, Mrs. Dale, standing by the linen-room door in the twilight of the dark green corridor, clapping and applauding no one in particular, while the nurses picked up their aprons and handed in their keys. I remembered too how stuffy it had been in the evenings, and how my hopes would rise when the evening hymn started up, and the curtains were drawn across, and the night nurses started to arrive.

‘So, you made some fertile friendships at the University?’ the Sister pressed, rearranging her words tenaciously. ‘You found a rich inheritance?’ She pursued. ‘Then perhaps when you leave here …? to pick up the threads …?’

No. I had not made any friends, even there. For apart from Helena, who would drop in for a hot milk-drink in the evenings, and bring the ‘Battle of Maldon’ for some translation (which she was not very strong on) I had never been caught up in the student world.

I used to envy them though, as they shouted across the Broad, waving from their bicycles as though they did not mind about the ungulates and the horned mammals having been there before them – got there first, so to speak. I used to envy them as they called down from top windows in Walton Street, or spoke across the library-desk:

‘Are you playing tennis this afternoon, Jane?’ and the reply would come ‘pat’ before I had even had time in my mind’s eye to string the racket so that the ball did not slip straight through the frame, while I was still wondering whether it was really cat-gut:

‘Sorry, I’ve got an essay-crisis.’

I had often tried to describe Oxford life to Mother. I would tell her how they dressed and spent their time. I used to describe college balls and essay-crises and afternoons on the river and vacation trips and coffee-parties when they would stay up till midnight talking; I told her about how they sometimes fell in love or got engaged, and Mother would say that it took all types to make a world and that she would not like her student daughter to become too ‘fast’, to which I would agree.

I once said I thought they were like good riders who never came off their mounts, and she reminded me that we need more than one spill in life if it was to be a rich one and a good one. To which I agreed. Mother smiled and said her girl had plenty of imagination.

‘Why do you not, one day, when “the moil” [meaning my final examinations] is over, “when the battle’s lost or won”,’ she said playfully, ‘try to write some little sketches about Oxford life and personalities and your college idols, remembering all sides of the picture …’

No, I had not made any firm friendships, even there.

‘You see, unfortunately,’ I tried to explain to the Sister, ‘unfortunately I did not seem able to learn exactly how the appropriate reply fitted on to the prior remark, and a lot seemed to depend on this in undergraduate circles. With me the two never seemed to dovetail.’

There had always been that strange hiatus, that funny in-between gulf that other things took possession of when you were off your guard, and surprised you unawares: the purple buddleia with the butterfly clinging, the kangaroo, the groves of spotted bananas, and the egg-eating snake with the enamelled prong in his throat (for piercing the shell with). They had always been there, these other things, and when the undergraduates spoke again or stood there waiting for me to affix the right reply, I was, if you see what I mean, a little flummoxed, a little behindhand; not quite up to the mark. I had been tapped on the shoulder, so to speak; I seemed to be reduced to silence by the things the others got round so easily.

And then the laughter came. For when they spoke again, those members of Oxford University with whom I consorted, I could only laugh. Gale fumbling with the zip of her evening gloves; Prue pouting over her make-and-mend or struggling with the little portable wireless. And outside were all these strange things, spotted or quilled or feathered.

‘It was because of all the other things,’ I explained to the Sister, ‘that I usually ended in laughter.’

Unfortunately, it did not go unnoticed, and one day at the Principal’s little termly tea-party for her third-year students, the laughter happened once too often.

She was pouring out tea, and one of the guests, a Miss Veronica Piercy, was discussing the yearly ‘Mission’ to the University.

‘I am afraid, Lady Stocker,’ she was saying, ‘that we are drifting near to a spiritual holocaust. Much as I admire these Aldermaston Marchers, and racial demonstrators, they surely tend to forget that in spite of all the material threats to our valuable Western contribution to civilization, a much graver one lies ahead in the form of a spiritual waste, a spiritual vacuum. For the blank apathy of the masses …’

There we all were, in a row on a striped Regency settee, in afternoon dresses – Miss Piercy’s was a pale violet mohair – passing the painted, transparent cups and the daintily rolled sandwiches that had been set before us. Lady Stocker nodded politely, and another guest cried with a great rush of approval:

‘I, Lady Stocker, I couldn’t agree more.’

As we sat there I could see the even-toed ungulates marching through the waste, and files of armadillos with scaly shells, and hosts of big black flies. The door opened … it was only the maid in a starched cap carrying the silver kettle, but the laugh I gave shocked even the Principal.

The animals … the animals … I wanted to tell them all about the animals, but would they understand? They say the English are great animal lovers. I don’t think this can be strictly true though. I supposed at least that I was a great animal lover;...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.7.2025 |

|---|---|

| Einführung | Daisy Johnson |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Klassiker / Moderne Klassiker |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-39026-9 / 0571390269 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-39026-7 / 9780571390267 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich