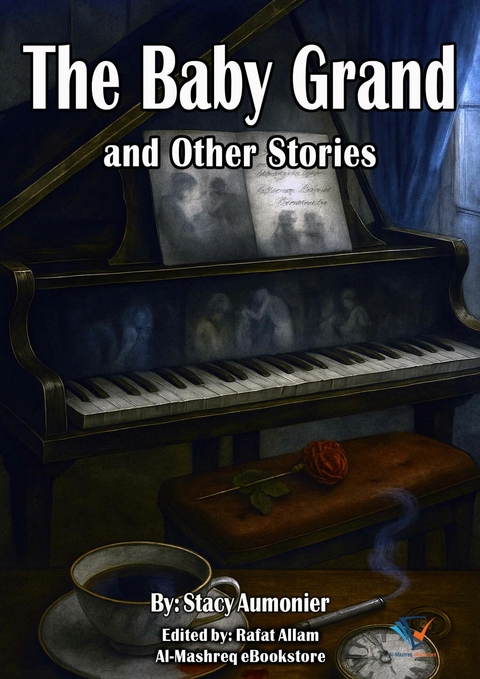

The Baby Grand and Other Stories (eBook)

200 Seiten

Al-Mashreq Ebookstore (Verlag)

978-0-19-561541-8 (ISBN)

Stacy Aumonier was a British writer and stage performer, acclaimed for his short stories that delved into the intricacies of human nature and society. Coming from a family with a rich artistic heritage, he initially pursued painting before turning to writing. Between 1913 and 1928, Aumonier published over 85 short stories, six novels, and several essays. His works were celebrated for their wit, insight, and emotional depth. Notably, Nobel laureate John Galsworthy praised Aumonier as 'one of the best short-story writers of all time.' Despite his untimely death from tuberculosis at the age of 51, Aumonier's literary contributions have left a lasting impact on British literature.

2. The Funeral March

She was a woman with a genius for apparent helplessness. She drifted around the verandah of the Hotel Reina Christa like an autumn leaf, and like an autumn leaf she was for ever changing her hue. She was always wearing different-coloured cloaks and shawls, which other people had to fetch for her. Not only men, but women. She was so helpless, you see. To me she was like a white flower, which one is only conscious of at night. One associated her with the night—the dead white face with the little flick of carmine on the lips, the blue-black hair, and those large, dark appealing eyes. She was always appealing, appealing for sympathy and understanding—and anything else. She seemed to give out nothing of herself. She was nebulous. But in my whole life? have never met anyone such a complete mistress of the verb schwärmen. It is a pity there is no real translation for this word, for she embodied it in her every phrase and movement. The women, who were for the most part middle-aged English and American women, staying there for health or pleasure, entirely succumbed to her. They found her most fascinating. She certainly could be amusing at times, and she had travelled a lot, and seen sides of life that appeared entirely romantic and remote to most of them. Moreover, she was Russian, which means so much when you are susceptible to mystic influences.

The men, I noticed, were a little afraid of her, but as they were men whose activities centred principally around golf and bridge it is not surprising. They did not like being asked about their souls, and when their physical beauty was praised openly before a crowd of people they felt self-conscious. But some of them seemed t? like to sit and talk with her—alone. There was one young sub—just out of the shell, with some of the yolk still on his hair—who became apparently wildly infatuated. He devoted not only his evenings, but many of the precious hours when he might have been playing golf to her. The frenzy lasted for ten days, and suddenly the pale youth disappeared. Poor Madame Vieninoff wandered the grounds disconsolately.

"Oh, my poor dear Geoffrey," she said to everyone. "What has happened to him? He was so sweet!—so sweet!"

She was discovered the same evening probing under the lilies on the pond beyond the pergola with a walking-stick. I think it was a disappointment to her not to discover that pale face floating amongst them. She was so helpless.

It must have been an even greater disappointment when it transpired that the young man had just remembered that he 'vas down to play in a golf tournament in a town fifteen miles away, and he had not had time to let her know. She soon, however, recovered from this. To that frumpy old Mrs. Wyatt she would exclaim: "Oh, my darling, how beautiful you look to-night! You must always wear cerise and black. What exquisite pearls! They are like your eyes, floating in the ether."

To little Mrs. Champneys she would say:

"Oh, my darling, come and talk to me. I am so lonely. You are so sympathique."

And she would tell Mrs. Champneys all about her dear beloved husband, who she said had been a great musician, and had died many years ago. She would sap this poor little woman's nervous vitality with her moving stories of love, and death, and passion, with her tales of suffering, interlarded with little flicks of cynical humour. She could blow hot and cold too. She was heard one evening screaming at her maid in French, on account of some trivial ill-adjustment of her frock. She sulked for an afternoon because a pretty woman named Viola Winch had occupied the whole of old Colonel Gouchard's time during déjeuner.

But for the most part she had it all her own way. There was little opposition. She was never so happy as when surrounded by some dozen of the hotel habitués listening to her stories, or absorbing her charm.

It was during one of these occasions that I noticed strange little occurrence. The evening train used to come in while the guests were at dinner, consequently the new arrivals usually dined alone, and either did or did not join the others afterwards.

I was seated in a chair on the verandah facing the dining-room obliquely. Madame Vieninoff was the centre of an admiring group as usual. I had never heard her so entertaining. The French door to the dining-room was open, and I observed an elderly distinguished-looking man with white hair and a pointed beard—one of the late-comers—dining alone. He was obviously tired from a long journey and in need of his dinner, which he enjoyed with the quiet satisfaction of a gourmet. He was nearing the end, and had raised a glass of wine to his lips, when? suddenly observed him stop, as though listening. He put the glass down, and frowned perplexedly, as though trying to associate what he was listening to with some past experience.

Then he finished his wine and pondered. After a few more minutes he stood up and came to the open door, where I was sitting, and looked out on to the verandah at the group of people. I saw his eye alight on Madame Vieninoff, and a curious cynical smile twisted his lips. He returned to finish his dinner. I could not see in the dim light whether she had observed him, but I noticed as he went back she was laughing rather hysterically at some reminiscence that she had herself been recounting. Then she became curiously subdued.

When the elderly gentleman came out to partake of his coffee and cognac, Madame Vieninoff had retired. She said the night was oppressive, and was affecting her nerves. I thought to myself: "Ho, ho!" which is another way of saying that we all love a mystery.

I made a point of engaging the newcomer in conversation, although, of course, it was impossible at the moment to talk about Madame Vieninoff. We talked about hotels, and the country, and sport, and other safe subjects which hotel guests interminably discuss. He was a quiet, cultivated Frenchman, prepared to be friendly, but not too communicative—not a man to be rushed or cross-examined. We retired early.

The next two days wrought an extraordinary change in Madame Vieninoff. There was no disguising it. She still drifted about the verandah, but it was in a furtive uncertain manner. She appeared petulant and no one could get a smile out of her. She was obviously, moreover, in dread of finding herself in the presence of this new arrival. She kept her room for hours, and sent her maid for time-tables, or to make enquiries at the bureau about the departure of trains to here, there, and everywhere, which was surprising, as she had told everyone that she meant to winter at the Reina Christa. The poor woman was in great distress, and it became apparent to my friend, whose name I discovered to be Louis Denoyel. Everyone observed that Madame Vieninoff was not herself, but I doubt whether anyone else, except myself, associated her agitation with the arrival of Monsieur Denoyel. On the third afternoon she carne on to the verandah, where I was drinking coffee with Denoyel. She glanced at us and darted away.

Denoyel frowned, and the cynical smile left his face. He stroked his beard, shrugged his shoulders, and muttered:

"Perhaps it's too bad! After all, she's a woman!"

He looked up at me quizzically, and I said:

"All of which I find intriguing."

He thought for a long while. Then he took out a visiting-card, wrote something on it, and rang the bell for the waiter. When the waiter came he said:

"Bring me an envelope, please, and I would like you to take this message to Madame Vieninoff."

The waiter was away for nearly five minutes, and I sat there anxiously hoping that my friend would show me what was written on the card. He was amused at my curiosity, and in a sudden whim he handed it across to me without a word. On it was written in French:

"Do not be alarmed. I am leaving to-morrow morning.—L. D."

When the waiter had taken the message, I said:

"Well, sir, you cannot leave it at that."

He lightly beat a tattoo on the table with his left hand, and then he said:

"No, I suppose, having gone so far, I must tell you the whole thing. But wait till this evening, and we will go out for a stroll along the bay."

The night was warm and fine, and seated on the carcass of a fallen pine tree at the edge of the dunes, just above the bay, Monsieur Denoyel told me this story:

"It's a strange story," he said, "because it is a series of contradictions. But all true stories manage somehow or other to contradict themselves; life is like that, I suppose.

"In the days when the ill-fated Romanoffs flourished and Imperial Russia was a force to be reckoned with, Serge Vieninoff was a musician of some repute in Petersburg. He was inclined to be lazy and had accomplished nothing very distinguished, but people were beginning to talk of his future. He had a considerable private fortune, and kept up a certain amount of style in the most fashionable quarter of the city. He was popular, amiable, and cultured. And then one day he met and fell in love with Wanda Karrienski. She was the daughter of a small innkeeper, and was at that time serving as a manicurist in one of the big stores. That is our friend across the way."

And Monsieur Denoyel nodded in the direction of the Reina Christa, whose lights were reflected upon the still surface of the bay.

"She was of the clinging,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.6.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Schlagworte | British Literature • Character exploration • Cultural Commentary • Early 20th Century • emotional depth • human emotions • Human nature • Humor • literary fiction • Narrative craftsmanship • Pathos • poignant tales • psychological insight • Short Stories • societal expectations • societal norms • Stacy Aumonier • Storytelling • thematic diversity • Wit |

| ISBN-10 | 0-19-561541-7 / 0195615417 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-19-561541-8 / 9780195615418 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich