Lost Folk (eBook)

320 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-38832-5 (ISBN)

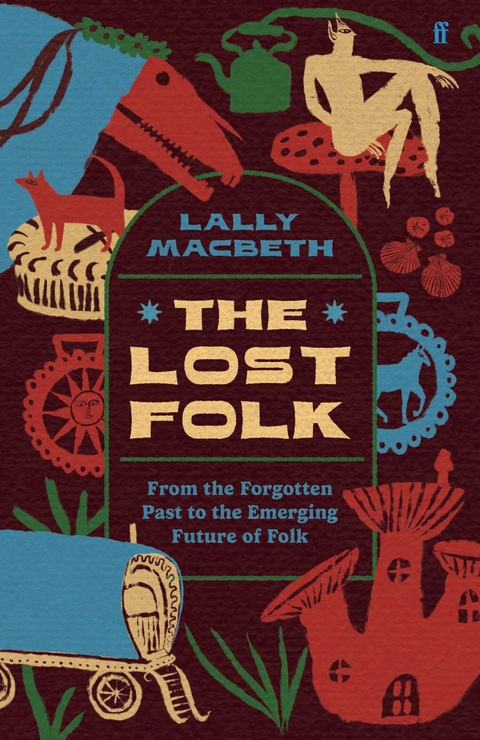

Lally MacBeth is an artist, writer and curator based in Cornwall. Her work takes in history, folklore, performance, ritual and artifice - and the links between high and low culture. She is the founder of The Folk Archive and co-founder of Stone Club. She has written for Caught by the River, House and Garden, and Hellebore, appeared on BBC Radio 3 and programmed events for the Tate, the British Museum and the ICA, amongst others. The Lost Folk, published by Faber on June 19th, is her first book.

'An exceptionally thoughtful and beautifully written.' Maxine Peake'Erudite, questing and endlessly fascinating . . . the book that British folk has long needed.' Katherine May'A splendid museum full of strange and wonderful things.' Peter RossA fresh and engaging celebration of the customs, places, objects and peoples that make up what we know as 'folk' in Britain. By its nature, folk is ephemeral: tricky to define, hard to preserve and even more difficult to resurrect. But folk culture is all around us; sitting in our churches, swinging from our pubs and dancing through our streets, patiently waiting to be discovered, appreciated, saved and cherished. In The Lost Folk, Lally MacBeth is on a mission to breathe new life into these rapidly disappearing customs. She reminds us that folk is for everyone, and does not belong to an imagined, halcyon past, but is constantly being drawn from everyday lives and communities. As well as looking at what folk customs have meant in Britain's past, she shines a light on what they can and should mean as we move into the future - encouraging us to use the book as an inspiration, and become collectors and creators of our very own folk traditions.

Folk culture is all around us: it is sitting in our churches, swinging from our pubs and dancing through our streets; it is patiently waiting to be discovered and appreciated, to be saved and cherished.

In 2020 I started The Folk Archive as a way to increase interest in folk culture. I wanted to highlight the ephemeral pieces of everyday life that often get overlooked and that I believed were in danger of getting lost, such as pub signs, church kneelers and corn dollies. I set out on a journey to record these objects, as well as folk customs, rituals and tales, with the hope that through saving them we might collectively learn from our past and to help inform our future. This vision of the past and future coalescing formed the basis of my motto for The Folk Archive: folk from the past, folk from the present and folk for the future.

For years I have scoured charity shops, car boot sales and junk shops for photographs, horse brasses, books, costumes: anything that I felt belonged to the category of ‘folk’. From these items a collection formed, but perhaps more importantly, so too did a methodology – one in which, both academically and practically, folk takes centre stage.

As a practice, it can be hard to define. For me, there are a few helpful pointers to establish if something is folk:

- Has it been touched or made by the human hand?

- Is it being made/performed with a particular locality in mind?

- Is it for and of the people?

There are, of course, a multitude of other questions you can ask yourself, but I find these are pretty helpful starting points, and they cover most objects, customs or places I’ll be discussing in The Lost Folk. At its core, folk does not belong to anyone; it is everybody’s – this is perhaps its most important and defining feature, and something it is key to remember in any consideration of a ‘folk’ object, custom or costume.

What is folk?

Before we look at what I believe ‘folk’ to be, I thought it might be useful to briefly define what has traditionally been considered as ‘folk’. Mostly, the term is used in relation to the traditional practices or customs of a place. This can be related to the music, art, dance or customs of a particular town or village, or of a particular country. Folk as a term involves both people who make ‘folk’ – those who perform it or create it – and those who ‘collect’ it.

The people who ‘collect’ it are often talked about as ‘folklorists’. These people work to collect folk practices, including folk dances and folk tales. In many cases, these collectors of folk have been from the middle or upper class, while the people ‘performing’ or ‘enacting’ the folk practices have been working class.* Collectors have traditionally had very particular ideas about what or who should enter the canon of folk. This has meant that many people, customs and objects have been left out.

As a whole, the canon of folk, as with that of other disciplines, has become one in which a select number of people have had an outsized voice in how it is collected and preserved for the future. Given that folk is of and for the people, it should not be so exclusionary, but instead for all of us to decide who and what is important.

In 1907 the folk song and dance collector Cecil Sharp, whom we will consider in more depth later, described folk music as ‘the song created by the common people’.1 This gives a sense, I think, of the pejorative way in which folk practice has been spoken about and recorded in the past: the ‘people’ were rendered as a generic group of nameless individuals from a particular class. So much of the way in which folk has been written about or discussed has implied an us and a them – ‘we are the ones who collect it, they are the ones who participate in it’. As a collector of folk myself, I aim to begin to redress this balance by actively engaging in folk practices local to me, and I can happily say this is a growing trend. I explore traditions that previously have been excluded because they haven’t met folklorists’ criteria for what constitutes folk, and I encourage everyone with an interest to do the same.

My vision of folk

It is important to note at this point that I don’t claim to be an expert on folk; it is such an expansive topic that it would be nearly impossible ever to truly understand it all. It is also constantly evolving and changing: just as you think you have a grip on it, it slips and morphs into something new. ‘Expert’ is generally an unhelpful term when talking about folk because both the making of folk and the collecting of folk should be an exchange of ideas, a coming together of community and a sharing of knowledge.

Although I would of course count folk songs, dances and customs among my definition of what folk is, nostalgia also plays a large part in my vision of folk culture. Including nostalgic recollections within a definition of ‘folk’ could be seen as being at odds with more traditional folk collection practices, where the emphasis has tended towards factual accounts based on information recorded by a perceived ‘expert’. However, for me, nostalgia is often at the heart of why things become perceived as ‘folk’ by people and communities.

Literally, ‘nostalgia’ means the yearning for a lost home. In the context of folk, this feeling can be applied more broadly to a lost place or object – somewhere or something mythic and unknowable, or belonging to a bygone time – that is held in the highest reverence by the people who remember it. A great number of folk customs encompass this nostalgia, but it can also be used in the context of much newer folk practices and objects, such as school plays, model villages and craft projects made from tinsel and crêpe paper, toilet rolls and bits of string. This is most readily seen in online Facebook groups and internet forums, where people gather together communally to reminisce about customs, traditions and places from a particular town or village – creating together an environment that feels like home.

While nostalgia is sometimes perceived as being rose-tinted – and it certainly can be – in my own folk landscape, I do not wish to do away with the gritty or more frightening aspects of folk culture: they matter, too, and are important in moving our folk practices forward into the future so they can be truly inclusive. I believe folk should be about the full breadth of human experience, from childhood to death, and that scope must include everyone and all experiences of the world.

Identifying new customs

The youth jazz bands of Newcastle might not be considered a ‘folk custom’ in a conventional sense, but they perform many of the same functions that other, more traditionally accepted folk customs do: they bring people together into a community and mark particular points in the calendar through parades that feature music and costume. Likewise, in Toxteth– an inner-city area of Liverpool – since 2017, each 23 November, people have gathered together to celebrate their recently and long-since departed friends and relatives at the Toxteth Day of the Dead. It parallels older traditions in the use of DIY materials to create costumes and props for a procession through the streets. But here, people are building a new tradition: they are building the folk memory.

The development of customs and the terminology associated with them are important aspects of the way folk culture evolves through history. The identification of new customs happens frequently, as communities evolve and build their own traditions. It is, I think, an extremely positive and exciting idea that folk can constantly move forward and that rather than being scared of the ‘new’, we can actively embrace it, alongside celebrating the past.

Many folklorists have served a vital function in evolving folk via the invention of new terminology, for instance the folklorist Ellen Ettlinger’s use of the term ‘religious folklore’, which she came up with at a point in history when many religious customs were in danger of being lost in an increasingly secular post-war world. Her use of the term threw new light on customs and traditions associated with the Church.

In my own work collecting and preserving folk culture, I have identified a series of customs and practices that falls under the banner of ‘municipal folklore’. These are all customs that, until this point, might not have fallen under the heading of folk because they have generally been associated with councils or institutions. Municipal folklore, like Ellen’s term, encapsulates a world of folk that has been largely ignored.

Customs, traditions and objects that fall under the category of municipal folk are varied, but their overarching and unifying factor is that, unlike many folk customs that are perceived as traditional, they sit not in the rural landscape but instead in the town- or cityscape. That is to say, they are all related to urban living in some way. This...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.6.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-38832-9 / 0571388329 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-38832-5 / 9780571388325 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich