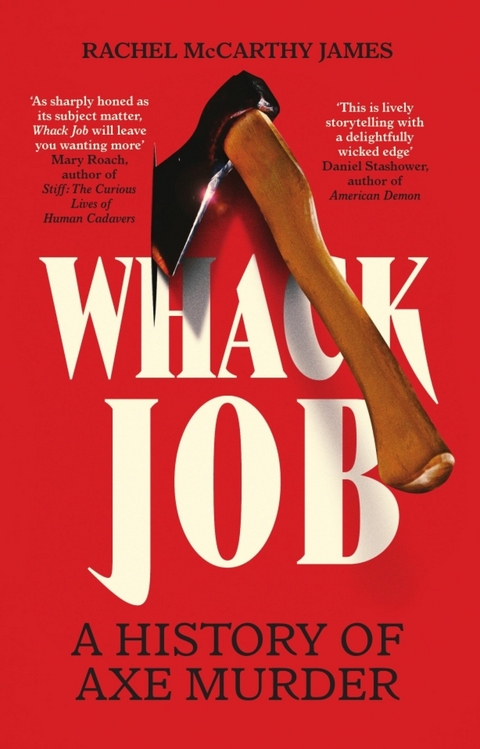

Whack Job (eBook)

288 Seiten

Icon Books (Verlag)

978-1-83773-327-9 (ISBN)

RACHEL MCCARTHY JAMES was born and raised in Kansas, the daughter of baseball's Bill James and artist Susan McCarthy. She graduated from Hollins University in Roanoke, VA, where she studied writing and politics. Her first nonfiction book, The Man from the Train, was written in collaboration with her father and published in 2017. She lives with her husband Jason and pets in Lawrence, KS.

INTRODUCTION

Nothing Could Be Simpler

Early on in the process of writing my first book about axe murder, I took a job working in an after-school program. I was twenty-six and I’d recently figured out a new answer to the hundred-year-old mystery of the murder of eight people in Villisca, Iowa. I needed a day job, and the children at the nearby elementary school I had once attended myself were a bright counterpoint to the grim work of researching true crime.

Mornings spent mired in awful murders were balanced by cheerful afternoons in sunny playgrounds and colorful classrooms, mediating disputes over nothing more serious than iPad time. At Pinckney Elementary, my job working in after-school care with the Boys & Girls Club was both more and less important than my work unearthing major connections between horrific tragedies. These kindergarteners had real struggles too, but I wasn’t a teacher or their parents. Anything major was above my pay grade. I had to make sure that the kids didn’t die, but only in the two or three hours they were in my care.

One day a little boy said something that struck me. The setting was the gym, a routine safety assembly. Fire was banal as a threat, routine, done to death. But in 2013, the possibility of a mass shooter was still novel and exciting enough to make the kids antsy. Especially since we were talking about school shootings like they were some forbidden R-rated movie. Barricading doors, running away, hiding, all of those things were covered—but we avoided mentioning the actual threat, the weapon, the gun.

The boy, a fifth grader, raised his hand, blurting out, “WHAT IF IT WAS AN AXE MURDERER?” He accompanied the question with a mimed motion and sound effect that was somewhere between light saber and baseball bat.

We just moved on without reacting—you can’t rise to the bait that way when you’re trying to get children to take something seriously. But the incident stuck with me. How did this child, born into the age of touch screens, have a reference point for “axe murderer”?

It makes sense that he wouldn’t say “what about a SCHOOL SHOOTER?” since that was the source of the very tension that the joke intended to relieve. Instead, he reached into his imagination and came up with a tool. Axes are a big deal in Minecraft, so I have no doubt that he understood that their primary purpose as a tool is to cut down trees. Axe murder, though, seemed a joke too dark for such a tender age. How was the violence of an axe murderer remote enough to be funny and yet familiar enough for a ten-year-old to invoke?

The boy’s antics stuck with me throughout the process of writing and promoting my book The Man from the Train. Like this book, it is a work of nonfiction. The man in question would ride the rails to a community where he had no ties, pick up an axe left outside in a woodpile, break into a house, and kill everyone inside; he especially targeted households with children. The book makes the argument that this pattern repeated dozens of times nationwide over about fifteen years and can be traced back to a man who evaded capture after murdering the family he lived with and worked for on a small farm in Massachusetts. From the beginning of my research process, the idea of the axe murderer as opposed to a murderer who used an axe was central to my understanding of these tragedies.

Newspapers embraced the grabby compound phrase slowly: in 1890, the term was almost never used, but by 1920 it was used frequently. Our fiend in The Man from the Train killed perhaps as many as a hundred people beginning in 1898. He began relatively slowly, slaying one or two families a year, choosing rural communities and leaving geographic distance between his attacks. We believe that he was following work opportunities—especially the chance to use the axe to fell trees as a lumberjack. In 1909, he ramped up the blood-shed and the events became more frequent and more tightly spaced. Though the idea of serial killers wouldn’t be formalized for decades to come, awareness of them was dawning among the crime-obsessed public. After the man killed two Colorado Springs families on a September night in 1911, headlines about the “axe-murder”1 began to take root in newspaper pages, especially in the Midwest.

The coverage of that event died out, but the phrase took hold with the trial of Clementine Barnabet. She was a young black woman in Lafayette, Louisiana, a troubled eighteen-year-old obsessed with cults and true crime who confessed to a series of murders in Louisiana and Texas—horrible crimes she (in my firm opinion) did not commit. Her vivid court statement involving voodoo rituals grabbed headlines across the country; white journalists found it easy to exploit their readers’ racism by placing exaggerated and obvious rumors into print. By the time the man from the train made his infamous trip to Villisca in June 1912, the phrase “axe murder” was a well-established part of the crime-writing lexicon, never to exit it again. It stuck to the Villisca event so firmly that when I first started research in 2012, the Wikipedia page for it was the first Google result for the phrase “axe murder.”

I once believed that the emergence of this wording in newspaper headlines also mirrored a surge in the use of axes themselves as a weapon, but now, having tracked the axe over so long a period throughout human history, I don’t think that’s true. Axes are at their core utterly common, and so they have been as ubiquitous as weapons as they have been as tools. They are everywhere in our story of violence, so much a part of the texture of our conflicts that they become banal, unworthy of note.

What made the phrase “axe murder” so charged in the 1910s was a clash of cutting-edge technology with ancient traditions in toolmaking over the previous sixty years. Industrialization would eventually make the axe fall out of daily use, but for a moment the new machinery made the humble axe omnipresent.

Battleaxes were thoroughly outdated by the Civil War, but in military and domestic settings there were more axes than perhaps at any other point before in history. Steel tool use proliferated after 1856, when a man named Henry Bessemer devised a new method of purifying iron quickly and inexpensively by oxidizing iron with pressurized air to remove carbon and other impurities. This one-step method was discovered in the process of producing cannonballs that could be fired in the manner of a rifle. Bessemer was driven to problem-solve after the British postal service stole his fiancée Ann Allen’s idea to modify the dates on embossed postal stamps, a grudge he held even after his steel foundry made him wealthy. Steel had previously been quite precious and rare, but unlike lab-grown diamonds its new availability and cheapness did not temper demand. Skyscrapers and trains and paper clips alike flowed out of the foundries, along with a flood of hand tools: hammers, shovels, hoes, and others were suddenly much more common and inexpensive. In the 1866 Fyodor Dostoyevsky masterpiece Crime and Punishment, the antihero Raskolnikov murders an elderly pawnbroker and her sister with an axe, grabbed from the kitchen in his apartment building. In the depths of his absurd and monstrous plans, in the chaos of Saint Petersburg and his own head, he settles upon the convenience of the axe: “nothing could have been simpler.”2

As electricity and plumbing and cars and telephones became increasingly accessible, the axe seemed all the duller. Guns supplanted the axe as the convenient weapon of choice. Chainsaws were used for a larger and larger share of forestry applications, though they weren’t yet in use in the home. Axes were becoming an object of slight kitsch. At the 1893 World’s Fair, a small glass version of George Washington’s axe was a popular souvenir. Carrie Nation—a leader in the temperance movement of the early twentieth century who raided and destroyed bars and speakeasies—remained an object of derision long after the repeal of prohibition, her tiny hatchet no equal for the country’s thirst. One brand of tobacco in the form of a plug (a brick of compressed tobacco leaves, to be cut off and chewed or smoked in a pipe) called itself Battleaxe, recalling a now firmly extinct era of violence to flatter male customers who want to think of themselves as rugged—not unlike the logic behind Axe personal care products today. The axe was still around, but becoming antiquated.

By 1922, the phrase “axe murder” appeared in U.S. newspapers hundreds of times each year, always used to describe actual crimes. But, like all grabby phrases, it became tinged with the grime of exploitative newspaper coverage through overuse. As the chainsaw took more and more of the axe’s main occupation, the axe became an anachronism.

The contrast between the axe (boring) and murder (exciting) gave the phrase a darkly comic tinge. By the 1950s, “axe murder” was still a staple of newspaper headlines, yet the phrase and indeed violence with axes itself was becoming a stock joke. In Shirley Jackson’s lighthearted book of domestic essays Life Among the Savages, she writes of a sleepy domestic scene perked up by violence: “I finally found an account of an axe murder on page seventeen, and held my coffee cup up to my face to see if the steam might revive me.”3 In 1955, Charles Schultz killed off unpopular character Charlotte Braun in an illustration that parodied the gentle humor of Peanuts by putting an axe in...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.5.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller |

| Schlagworte | axe • Helter Skelter • in cold blood' executioner's song • lizziwe borden • rubenhold • Shining • single subject history • The Five • True Crime |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83773-327-9 / 1837733279 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83773-327-9 / 9781837733279 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich