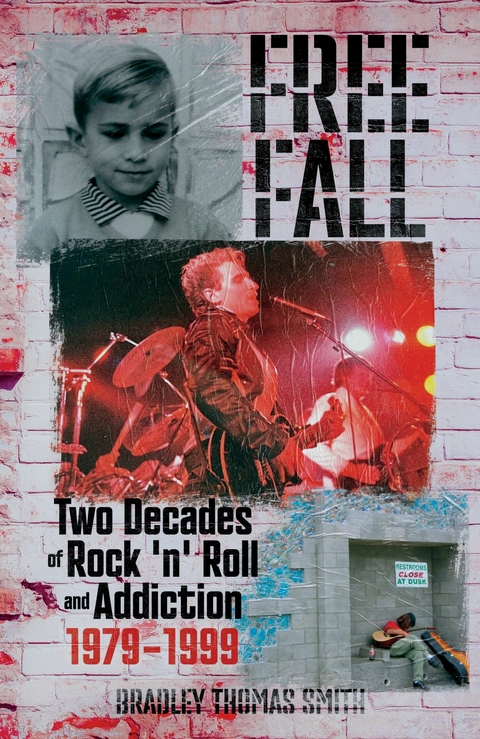

Free Fall: Two Decades of Rock n' Roll and Addiction (eBook)

236 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3178-0088-8 (ISBN)

Bradley Thomas Smith is a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor and a Licensed Advanced Alcohol and Other Drug Counselor at a university in Los Angeles, where he also teaches. There he is the Director of the Center for Collegiate Recovery, guiding initiatives for prevention, early intervention, and harm reduction for substance use disorders in emerging adults. His work includes community mental health education, research, and social justice advocacy. Bradley is also a psychotherapist in private practice and the bandleader of the classic rock musical group 'Leo Clarus' - The Clear Lion. He is twenty-four years sober.

First of a two-book series, Free Fall is a true-life musical memoir; not about how one gets better, but how one gets sick and doesn't notice. The astonishing account of escaping addiction and rebuilding a life is shared in the second book of this series, Falling Up. In Free Fall, a grieving child becomes a legally emancipated teenage runaway and pursues a rock and roll dream and gets close. Ideas of meaning and identity, formed by a bewildered boy soothed only by books, an AM/FM radio, a flimsy record player, and a guitar would ultimately lead a grown man into brokenness. It would just take 20 years of rock 'n' roll adventure; one that was frequently brave and doomed from the start. Free Fall is driven by a piece of bad luck: There were reasons to believe. Included with the audio book are 21 original songs, all written and recorded during the same time period, each song with its own writer's note. All produced by an intermittently homeless man hurtling towards end-stage addiction. By broadening the reader to listener, the music conspires with the book to reveal the unsaid. The music spans from lush ballads to wall-of-sound rockers, to a movie soundtrack pitch, a Christmas song, and a "e;lost demo"e; from a dusty cassette. There is no need to listen to the book in order. The chapters in Free Fall are short, with the introductory sections seeking to illuminate some of the cultural, biological, psychological, and philosophical intersections that can conspire to propel addiction. Simple, bullet point suggestions to help those who suffer are included; often containing sensible metaphors to help untangle addiction's maddening complexities. Chapter One, "e;Living for a Song"e; opens the story. Hard questions drive: How does an innocent child end up in a box on the streets? When does one "e;decide"e; to become a songwriter - or a painter, dancer, actor, or poet? What cultural and historical conditions shape this call? What beliefs sustain such perilous allegiance to this identity? How can songs this good go nowhere?Why was the near-lethal use of alcohol and drugs logical and defensible? Questions like these center Free Fall within a larger ether, and the story no longer seems so reckless. Similar intersections confound the seekers, the dare-to-dreamers, the wounded, and the disconnected everywhere. People are meaning-making creatures; all of us are compelled to make sense of our experience, to seek connection and pursue vague longings, and when we falter, to seek again, to learn as we go how to soothe our wounds and apprehensions. In the absence of connection, we create surrogate relationships, however harmful or illusory. These substitutes are a rational response to barrenness: anything but nothing again. While a cautionary account of the extraordinary risks to literally living for a song, Free Fall is also an inadvertent love letter to the songs of the late-Sixties and Seventies, to vinyl records and their precious liner notes, and to the pre-internet era of broadcast radio's last golden age, when deejays were the arbiters of cool. When the sparse, transient lifestyle of a musical troubadour still held a shred of dignity within a larger, fading myth. Free Fall introduces a nine-year-old boy and his first drink at the funeral of his beloved mother, dead at 33. Nobody noticed the drunk child. Well-meaning adults, distracted by their own disarrays, could not see. The boy began to seek something specific: a way to become so valuable he could never be abandoned again. At 17, the teenage runaway was a daily drinker and well on his way to a rock 'n' roll disaster. Free Fall closes with a crushing brokenness and a murmur of the divine. Browse the lyrics and their backstories, find a lyric that strikes your muse, and download the song using the QR code that brings you to https://bradleytsmith.net. However you may begin, consider the sheer audacity of it all. A man can cover a lot of airspace in free fall.

Author’s Note

Looking back is risky business. Our very identities are continually reconstructed by our memories, and those memories are stories. Each of us tells a private story about ourselves to ourselves, and then we carefully present selected parts of that interiority to the external world. Both versions—the story we tell ourselves and the story we present to the world—are complex and elastic. These stories are fluid tapestries of recollection and experience, themselves supple intersections seeking to make sense of the world around us and our place in that world, and to preserve our dignity within it.

Dr. Pamela Rutledge agrees, offering that “Stories are how we think, how we make meaning of life. These can [be termed many things], schemas, scripts, cognitive maps, mental models, metaphors, or narratives. Stories are how we make decisions, persuade others, create our identities and define and teach social values.”1 By far, the largest component of the story that we tell ourselves is memory.

There are perils to memory. In subtle ways unknown to us, our story may not be at all as we remember it. Neuroscience suggests that the very act of remembering transforms our memory as it is “reconsolidated” within our neural pathways. This means that across time, our most durable memories are those we have continually remembered. Tiny reinterpretations evolve, contoured by new emotional saliences that may be innocently unfaithful to the original experiences. In his memoir, Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov conceded he was recreating his life as he wrote.2

Still, we are meaning-making creatures, and stories are how we organize our meanings and experiences—for ourselves and others. At some point, we all become stories.

People change too. Lessons and sorrows accumulate. Triumphs and tragedies appear and recede. Ideas about our identity constantly evolve, often unaware that they are captive to external conditions. Cultural, educational, and economic forces can profoundly shape our identity—even our historical location matters. Grieving John F. Kennedy is different than grieving John Lennon, although only seventeen years separate those two distinct eras.

This suggests “the self,” like memory, is neither fixed nor predetermined but continually unfolding—“becoming,” as Aristotle might say.3 Even the most obstinate of us are preconsciously steered by hidden winds of context and seemingly whimsical encounters with intersections that are beyond our awareness and therefore not of our direct choosing.

Many times, a fallible memory is a blessing. An imperfect memory not only tends to protect and soften but can also lead to extraordinary ways of creating an essential personal belief. For example, there is an idea, loosely attributed to French philosophical thought, which holds that every time we invoke a loving memory, that memory becomes a tangible aspect of everlasting life. This may not be “true” at all. But if we choose to believe it, we can be comforted by the sense that our ancestors and departed loves are again with us, re-arriving into our longing and remedying that most awful aspect of grief: undelivered thankfulness. There is a beauty here that transcends the precision of truthfulness: by virtue of memory, all of us can re-embrace those we still love in a special aliveness. In doing so, belief becomes more important than the “truth.”

Fortunately, Free Fall is somewhat tethered to what historians call primary sources—in this case, the original music and lyrics that were written and recorded within a specific cultural and historical period, 1979–1999. More accurately, Free Fall is linked to the primary sources that survived that era. This is helpful; Free Fall is no longer solely hostage to memories that themselves are refashioned survivors. Twenty-one sets of original lyrics are contained here, each with a writer’s note and mirrored by a song title and music on an accompanying compact disc (hardcover only) or other media. It is these songs and lyrics that are the heart of Free Fall.

Regardless of fancy theories, philosophies, famous quotes, or academic tethers, Free Fall cannot evade the autobiographical. Benjamin Franklin remarked, “An autobiography usually reveals nothing bad about its writer except his memory.”4 George Orwell offered that “autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.”5 Fawn Brodie applies the coup de grâce: “A man’s memory is bound to be a distortion of his past—in accordance with his present wishes. Even the most faithful autobiography is likely to mirror less of what a man was than what he has become.”6 Perhaps so.

Writers who have gone before helped guide me through the very real awkwardness and vulnerabilities that stalk a memoir. Sherman Alexie spoke plainly: “In a sense, we’re all mythologizing our lives; it’s always an effort to make yourself epic. At least in fiction you can lie and sort of justify your delusion about your ‘epicness.’ But when you are writing a memoir, you’re trying to make your life epic and it’s not—nobody’s life is.”7

These lofty musings on autobiography are instructive, yet producing such a book still presents practical and editorial considerations that seem to pivot on what will be omitted. As a general rule—and acknowledging the fallibility of memory and the recognition that not all omissions are purposeful, just unremembered—if an experience was mean-spirited, cruel, or may reanimate the aggrieved, it is not recounted here. If I am merely resurrecting a wound, or a knowable insult may be done to the living or to the departed, I have avoided it. There is little kindness in stirring grievances. Especially the imagined ones. The heart of the story here is simple: living for a song and what that looked like in the real world. As for those omissions, the lyrics may be more sublime. There is a lot of space between the lines where the unspoken can be heard. This entire book is written through the lens of those lyrics.

This is also not a story that centers on “I drank this drink recklessly or did that exotic drug excessively and then this crazy thing happened.” While there is some of that, the harrowing consequences that followed these drinking and drugging episodes were rarely direct or sequential. There is a larger story: how the chronic use of alcohol and other drugs—painkillers— shaped a way of living that was both defensible and ensured regular collisions with the dire. These episodes are shared in the spirit of deepening the totality that produced these songs.

A fundamental principle guided these narrative choices: most of us were doing the best we could, with what we knew to do, in a complex world and with the consciousness we had at that time. We are doing that very thing right now. All of us wish we could have a do-over now and then. All of us long for forgiveness.

The action of forgiveness can be as simple as the choice not to punish. We can still feel the wound and recoil from its cascade of heartless whimsy and unwelcome lingering. The awful act may still feel fresh and wicked, its memory persistent and intrusive, yet we can choose to not demand our version of justice be exacted upon it. We have all faltered painfully at times. As a sixteen-year-old Jackson Browne wrote in “These Days,” “Please don’t confront me with my failures—I had not forgotten them.”8

I seek the same consideration Browne does. I remember the failures. Like most who have been fortunate enough to lead a long life, regrets and sorrows have accumulated. For all of us who are brave enough to look closely, there tends to be a dominant, specific sorrow, a remorse whose atomic weight is just one molecule heavier than all the rest. This molecule also carries shame. The lyric that ends the second verse of “Be Like You,” gives this metaphorical molecule a name: “One particular tear.” Like many lyrics here, this metaphor contains an aspiration to grace.

There is a practicality in the choice to not punish. If we allow our internal world to careen into grievance, we risk becoming what we behold. It is unwise to allocate our attention to seductive resentments and their justifiable bitterness. An especially important mentor once shared with me that “bitterness is unfulfilled revenge.”9 This revenge is invested in exacting retribution, not justice. The mentor cautioned me to be vigilant against my own vulnerability to this hungry ghost, warning that bitterness devours precious psychic calories that could otherwise be directed towards wonderment, creativity, and joyful usefulness. In this way, the mentor softly suggested, forgiveness also becomes an antidote to the secret contempt I felt towards myself. He invoked Helen Keller’s words: “Although the world is full of suffering, it is also full of the overcoming of it.”10 You must choose, he said.

Many justifiable resentments—the worst kind—are omitted here. These especially durable resentments do not serve the spirit of the story, only leave the lingering tang of the wound. Viewed through the long throw of time, resentments can be thought of as responses to indifference. Indira Gandhi, once prime minister of India, believed that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.4.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3178-0088-8 / 9798317800888 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 11,1 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich