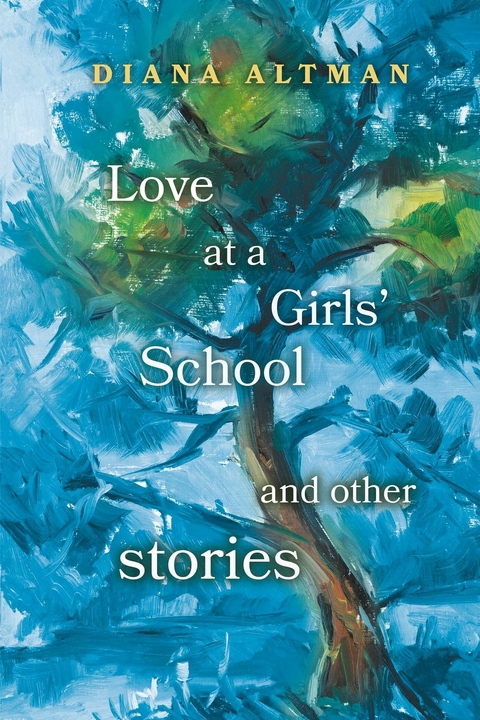

LOVE AT A GIRLS' SCHOOL (eBook)

176 Seiten

Tapley Cove Press (Verlag)

979-8-218-36937-8 (ISBN)

Diana Altman is the author of Hollywood East: Louis B. Mayer and the origins of the studio system, a book of film history. Her award-winning novel In Theda Bara's Tent was described as 'sophisticated storytelling' by Library Journal and as 'enthralling' by Publishers Weekly. Her recent novel We Never Told was selected by NBC News as one of 20 great summer reads. It received a 5-star review on Booklist and won first place/gold in the 2020 Feathered Quill Book Award contest. Altman's short stories have appeared in North American Review, Trampset, Notre Dame Review, StoryQuarterly, Cumberland River Review, Natural Bridge, and The Sea Letter. Articles have appeared in the New York Times, Yankee, Boston Herald, Forbes, Moment, and elsewhere. She lives in New York City where she is an Authors Guild Ambassador. She was a former President of the Women's National Book Association, Boston. She graduated from Connecticut College and Harvard University. www.dianaaltman.com

RECEPTIONS WITH THE POET

The poetry of William Carlos Williams now makes sense to me. In trying to reconstruct what it was about the poems that had seemed obscure, I see myself at college sitting cross-legged on the shag rug of the poet Theodore Howland who held his writing seminar at his farmhouse a few miles from campus, in Connecticut.

He was forty-eight, dressed in brown corduroy jackets and soft flannel shirts, and lived with an apricot-colored standard poodle. He had published several volumes of poetry, had won a Pulitzer, and had been a bomber pilot in World War II. With logs burning in the fireplace, he sat in a leather armchair smoking cigarettes as he taught us how to read from the writer’s point of view and showed us the choices writers make. For instance, Shakespeare used the word never five times for King Lear’s description of when he would see his dead daughter Cordelia again. Never, never, never, never, never. Say it four times, it’s different. Say it six times, it’s different in another way.

My fantasies about Theodore Howland were odd, even to me at the time, sitting among the other girls gathered in his cozy living room. I imagined myself in his bathtub, the old-fashioned kind with feet, though I’d never seen his bathtub. Mr. Howland comes in, picks me up out of the tub, and dries me off. I rehearsed that scene over and over, as he sat in his armchair listening in his encouraging way to everything my classmates said.

Sometimes I tried to force my daydream out of the steamy bathroom and into the bedroom, but even there it was chaste. He put me to bed under fluffy eiderdown, tucked me in, and I drifted blissfully to sleep. It did not occur to me that the comfort I derived from imagining Mr. Howland taking care of me like a baby might have had something to do with feeling too alone in the wide world.

I assumed everyone felt cast adrift at college. You made yourself tough. Those girls who had to return home freshman year seemed unbalanced to me and made me glad I didn’t have a home to tempt me. I couldn’t give in to homesickness because my mother was traveling in Europe and my father now lived with his mistress. Mr. Howland was my trusted older person. He gave me A’s and I believed myself to be his pet.

One of our assignments was to write in a journal every day. Some of the girls in the seminar filled in their journals the day before they were due. I had been keeping a daily journal for years. It was irrelevant that Mr. Howland wanted to see it once a month.

It was jarring, though, to see his handwriting on my pages. Handwriting is as distinctive as body smell and he made his too pungent by using red ink. “This is wonderfully unself-conscious,” he wrote after one of the entries, and I wondered what he meant. Why would I be self-conscious writing in my own journal? I liked putting into words what went on with my boyfriend when I visited him on weekends at the Yale Medical School dorms, how we made chocolate pudding on his hot plate and ate it with vanilla ice cream melting on top, how we listened with a stethoscope to a kitten’s heart going a mile a minute, how he studied at his desk with his right leg jiggling up and down while he hunched over medical books full of alarming illustrations.

The joke back in the Sixties was that girls went to college to earn an MRS degree, but it wasn’t funny to those of us who graduated without it. It felt dire not to be chosen, not only because it seemed to mean that we were not loveable but because nothing in our liberal arts education could translate into money to pay the rent. That I would have to take care of myself became clear senior year. How could I love him so much more than he loved me? How could I want to get married to him and he didn’t want to get married to me? Could anything hurt more than this? Could anything be more humiliating?

Since getting married was the goal, the best plan was to go where the most boys were. I applied to Harvard. And I was right. The place was full of boys. One week I went out with eight different ones. I’d gone from famine in New London to feast in Cambridge. What was I thinking going to a girls’ school? I’d been in a nunnery and didn’t even know it. I must have been out of my mind. But it was worth it, I told myself, because I was able to study with Theodore Howland.

I had no intention of having my heart broken again, so the man I spent the most time with at Harvard was not only married with a son but was also a foreign student who intended to return to Athens at the end of the term. I mention this marriage-defying affair only because of what that boyfriend said about Theodore Howland who arrived in Cambridge one weekend to read at the Houghton Library.

I wondered what was so special about the Houghton Library that female students were not allowed to use it. I expected something mysterious like you might find at a séance, but it was just a bookshelf-filled, hushed space like any other small library. I was excited to see my teacher again after a lapse of six months. I’d spoken fondly about him to my Greek boyfriend, who had come with me to the late afternoon reading.

There, at the podium, was Mr. Howland, with that deep cleft in his chin and a bit more gray in his dark hair and in his bushy eyebrows. He had a straightforward way of presenting his poems—no drama, just the words with whatever power was in them. When the reading was finished, I had no luck getting close to Mr. Howland because he was surrounded by admirers. I was miffed because I thought of him as mine. I turned to retreat, raised my hand to wave a quick goodbye, and he called, “Wait. You’ll go with me to the reception.”

I worked my way through the crowd to find my boyfriend. “Did you like it?” I asked him. “No,” he said. “That guy’s got no balls.” This seemed an odd thing to say after a poetry reading, and I wondered if I was blind to something about Mr. Howland. This was the second disparaging thing I’d heard about my teacher. At college graduation my older sister had said, “That’s the one you like so much? That guy with the degenerate face?”

His reception was held at one of those charming antique houses that line the side streets near Harvard Square. The place was packed with scruffy-looking students and with the luminaries of the Harvard English department. I sipped wine, lifted canapés off a tray circulated by a butler, and listened in on conversations. I kept hearing the words Mrs. Bernard DeVoto. The widow, Mrs. Bernard Devoto. I think we might have been in her house. The words were said with reverence and I wondered how a woman could disappear so entirely that she would acquire the prominence earned by her husband’s work and would become known only by his name. I loved those words, Mrs. Bernard DeVoto and said them to myself over and over again instead of striking up a conversation with someone. I milled around for an hour or so, then searched for Mr. Howland to say goodbye. When I found him he said, “No. You’ll stay for dinner.”

I imagined a banquet table with dozens of place settings but there were only eight of us and I was the only young person. We sat in straight-backed chairs in a circle in the living room in front of the fire balancing plates on our laps. A Longfellow scholar told us about the time he and Doris traveled by train to Chicago where he was supposed to teach. Susie had just been born, and they didn’t know what to do with Susie’s dirty diapers, so the Longfellow scholar told us that he went to the back of the train and tossed the diapers out onto the tracks. Then he roared with laughter and so did the others. The Milton scholar announced that their colleague at Princeton did not get tenure. The Victorian literature scholar said that when their colleague went to his summer home in Pomfret to finish that book he had promised Little Brown, the roof was infested with bats, which he tried to kill with his tennis racket. As the evening wore on the talk became exclusively about people I didn’t know, and some of it was so catty that I had to rearrange my idea of the loftiness of intellectuals.

It was obvious by the flush on Mr. Howland’s face that he’d had a lot to drink. As we were finishing dessert, he said, “Hey, listen to this!” And the separate conversations stopped and we all turned to him sitting in his chair. “I have to tell you something.” He laughed and groaned and took another sip of wine. “Oh, God, it’s so embarrassing. Listen to this.” He looked to the ceiling and took a deep breath. “I’m standing by the door, and I see Perry Miller. Jim, you told me Perry Miller was coming, didn’t you? You know how I admire him. Didn’t you tell me Perry Miller was going to show up? So I go up to him, and I wring his hand, and I say, ‘Mr. Miller this is indeed an honor!’ And he says, ‘I’m not Mr. Miller. I’m the butler.’” We all laughed, and someone said, “But didn’t you notice his uniform?”

Mr. Howland gasped for air, “Yes, yes, but I thought it was a tuxedo!”

Later, both of us bundled in our winter coats, he drove me to my dorm in his tiny Volkswagen and slowed to a stop on Mass Ave in front of Wyeth Hall. He said that once in a while a student comes along that makes teaching fun, makes you remember why you became a teacher in the first place, and I was one of those students, and he was grateful to me. I was so embarrassed, I just sat there wishing to evaporate. “Thanks for coming to that thing with me,” he said. “Was it too...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-218-36937-8 / 9798218369378 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,1 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich