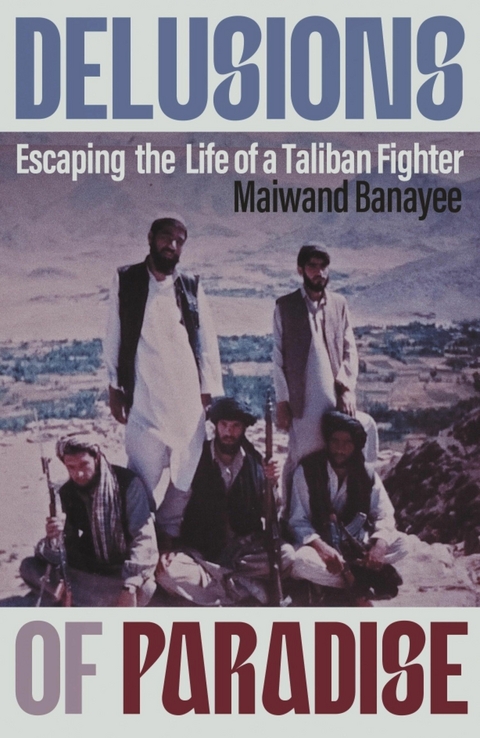

Delusions of Paradise (eBook)

320 Seiten

Icon Books (Verlag)

978-1-83773-192-3 (ISBN)

Maiwand Banayee was born in in Kabul at the onset of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. By the time he was twelve the country was engulfed in civil war and he fled to a refugee camp, where he enrolled in a madrassa and joined the Taliban. At 22 he rejected Islamic extremism and sought asylum in the UK, eventually living in Ireland before returning to England. He has been published in Stinging Fly and War, Literature & the Arts: An International Journal of the Humanities. This is his first book.

Maiwand Banayee was born in in Kabul at the onset of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. By the time he was twelve the country was engulfed in civil war and he fled to a refugee camp, where he enrolled in a madrassa and joined the Taliban. At 22 he rejected Islamic extremism and sought asylum in the UK, eventually living in Ireland before returning to England. He has been published in Stinging Fly and War, Literature & the Arts: An International Journal of the Humanities. This is his first book.

Chapter 1

THE CALL TO PARADISE: PESHAWAR, PAKISTAN, 1996

When I was sixteen, I wanted to become a suicide bomber for the Taliban in Afghanistan. Fortunately, I didn’t stick with it. Now, when I look back on that young man and the ignorance, delusion and false narratives he took as truth, I feel empathy for the boy that I was. And I shudder with fear for today’s generation of young men and women, who are once again living under the Taliban’s harsh rules and are being brainwashed into destructive ideologies.

I was born in Kabul in 1980, the year Soviet troops invaded my country and bombed rural Afghanistan to ashes, killing men, women, children and animals. Then the American-backed mujahedeen took over in 1992, and the bombs and bloodshed continued in a neverending civil war that reduced Kabul to rubble. Growing up amid the Afghan wars, I’ve seen what no child should ever see. To tell you the truth, I’ve never known the free and peaceful Afghanistan of my parents’ generation and those before them. The golden age of the 1960s and 70s – when Kabul, ‘the Paris of Central Asia’, was a cosmopolitan city flush with European and American tourists. Young people shopped in record shops, mingled at cinemas and co-ed college campuses, and women wore miniskirts and makeup, had jobs and weren’t imprisoned in their homes. Surrounded by majestic mountains, Kabul was once full of beautiful old buildings, palaces and gardens, and was famous for its roses and grapevines. By the time I reached my teenage years, Kabul was a ghost of a city, a war-torn place of ruins, where so many lives were lost, broken, marginalised.

I will begin my story when I was sixteen and studied at a madrassa (Islamic seminary) in the Shamshatoo refugee camp in Peshawar, Pakistan. A cluster of mud houses dotting the sweeping arid landscape of stones and rocks, Shamshatoo was one of 150 such camps that had been built for 3 million Afghan refugees fleeing the anti-Soviet war. It was a hotbed of radical Islam where Osama bin Laden found recruits. I’d fled wars in Kabul two year ago in 1994 and settled there with my family.

For those of us living life in these refugee camps, the madrassas were an important part of our day. One morning, just like any other, I painted my eyes with kohl, put on my white turban, and headed down the mud street toward the madrassa on the outskirts of the refugee camp. I removed my sandals and entered a bamboo-roofed mud hut, murmuring, ‘Assalamu alaikum.’

Mullah Asad, the bony-faced tafsir (exegesis of Quran) teacher sat at the head of the class behind a low Quran table, his bushy beard nearly reaching up to his eyes. He took off his white silk turban and ruffled his long black hair. ‘Waalaikumsalam,’ he said to me. ‘You’re late again this morning.’

‘Forgive me, saheb, I couldn’t sleep last night.’ Like the rest of the Taliban (students), I sat cross-legged on the threadbare carpet, leaning against the mud wall. After I opened my Quran, a talib (student) on my left, dressed in tatters, showed me the day’s lesson: The Chapter of Time.

Mullah Asad read, ‘By the passage of time, indeed, man is in loss …’ (Quran 103:1). He looked up from the large ornate copy of the Quran spread on the table in front of him. ‘Subhan Allah! Allah says we are losers. Young boys, this world is nothing but a mirage. A home that perishes is not a real home. A life that falls to death is not a real life …’

I was green, scared, broken and hungry most days. Mullah Asad’s words sent a pleasant hum through my blood, and with it I saw my existence as a waste of time on this earth. For much of my life, people had treated me badly, and I had witnessed so many horrible things that now I blindly embraced any opinion my madrassa teachers put forth. Anything seemed better than my painful, pitiful life.

Mullah drew a long breath. ‘The life of this world is like a shadow. The more you chase it, the more it runs away from you.’ He raised his voice. ‘Allah says in the holy Quran: Wherever you are, death will find you, even if you are in lofty towers …’ (Quran 4:78).

He paused to adjust his turban. ‘Talibano, if you want a real life, follow Allah and his prophet’s commands. And surely Allah will reward you in the hereafter with everything you have longed for in this life. Subhan Allah!’ He raised his eyebrows and smiled. ‘Once you enter Jannah [paradise], Allah will greet you at its doors, saying, “My pious worshipers, congratulations on immortal life.” In Jannah there will be no illness, old age, hunger, hurt, shame or guilt.’

The words ‘no more guilt’ rang in my ears. I had been feeling guilty, it seemed, for my entire life: guilty for being a coward, for not standing up to bullies, for not defending my name; guilty for disappointing my father. Mullah looked down at me and asked, ‘Are you afraid of death?’

‘No,’ I lied. I constantly lived in fear. Despite finding solace in Islam, the sounds of artillery still echoed in my ears and tormented my thoughts. Some nights I woke from terrible nightmares.

‘Congratulations on your eternal youth!’ He addressed us as if we were already inside paradise. ‘Jannah will be guarded by angels. There will be beautiful palaces made of gold, silver and precious stones. There will be dazzling white horse and camels. There will be delicious foods, rivers of milk, wine and honey …’

Breakfast that morning was stale bread and green tea, without sugar. My stomach growled, and I imagined myself sitting on a riverbank in this gold-lit paradise, eating honey with milk, warm bread, fresh apricots, dates and cherries.

Mullah nodded, smiling and enjoying his own fantasy. ‘In Jannah, there will be beautiful virgin houris with big chests, white skins and appetising lips. You can have sex with them all day long. The houris in Jannah are a million times more beautiful than the girls of this earth. Their beauty grows every time you look at them and have sex with them ...’

As Mullah grew more and more enamoured with the houris, I got an unwanted erection. With the Quran on my lap, it had to be a sin. I lifted the Quran from my lap, bent forward, and placed it on the floor in front of me.

‘But remember, young boys,’ Mullah said, ‘your deeds in this world will count toward your place in Jannah. The greatest level of Jannah, Jannat-ul-Firdaus, is close to the throne of Allah. Only chosen individuals will be permitted entry there, where they will rejoice in Allah’s company.’

‘Who are these chosen people?’ I asked, curious.

‘They are mainly martyred and very pious people.’

‘Will there be houris in Jannat-ul-Firdaus?’ asked another big-nosed Talib wearing an oversized turban.

‘That is crazy. Houris are always available, but the vision of Allah is the greatest of all rewards.’

‘Does a martyr meet houris the moment he dies, or will he meet them after resurrection?’ I said.

Mullah quoted a Hadith this time. ‘Once a companion of the Prophet Mohammad attained martyrdom in the battlefield. The Prophet sat by his head and smiled. The rest of his companions asked, “Oh Prophet of Allah, why did you smile?” The Prophet said, “I saw houris beside this Shaheed.” Based on this hadith, it is more than likely that a Shaheed will receive houris the moment he dies.’

‘I’m sixteen now. If I embrace martyrdom, will I enter Jannah at the same age?’ I said.

‘No, everyone will be 33 years old.’ Mullah reflected for a moment. ‘Talibano, don’t think about how old you will be in Jannah, but rather about how to achieve it.’

I couldn’t help but wonder if a six-month-old baby died, how would he know himself as a 33-year-old man inside this heaven? But I immediately read my prayer and begged Allah to drive away my doubtful thoughts. Then I was like a blind sheep that anyone could lead to slaughter.

Later that day, the rest of classes were cancelled because we had to attend a jalassa (conference) protesting the CIA’s ban on Dawat University, which stood near Sayyaf’s, a mujahideen leader’s refugee camp in Pebbi, another mud-brick Afghan refugee camp from the anti-Soviet war era, ten kilometres from our camp. That university had been established in 1980 through Western aid for Afghan refugees of the anti-Soviet war, but in 1995 it had become linked to international terrorism because of the assassination of two CIA officials and the World Trade Center bombing in 1993.

The jalassa was near our madrassa, so we arrived early. A large crowd of camp residents, mostly bearded men in rags and shalwar kameezes, squatted on a barren, dusty ground before a podium draped in green cloth with Quranic inscriptions. The posters on the wall behind the podium showed demolished mosques in Lebanon, Palestine and Bosnia, mutilated children’s bodies, and copies of the Quran strewn amid rubble. One poster showed Israeli soldiers kicking old men off their prayer mats, and another showed veiled women crying over coffins.

Those posters just reinforced my...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.4.2025 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | Achilles Trap • afgansty • Afghanistan • Bin Laden • boys in zinc • Directorate S • escape from kabul • Ghost Wars • I Am Malala • Kabul • kite runner • Rory Stewart • Steve Coll • Taliban • terrorism • theo farrell |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83773-192-6 / 1837731926 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83773-192-3 / 9781837731923 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich