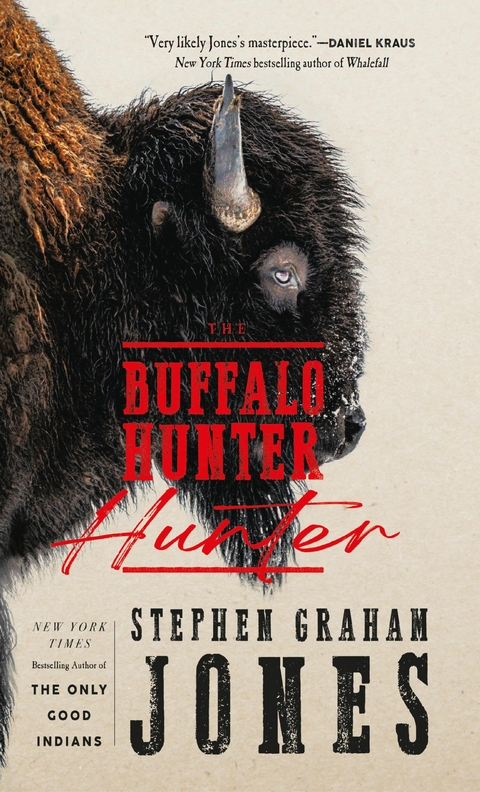

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter (eBook)

448 Seiten

TITAN BOOKS (Verlag)

978-1-83541-432-3 (ISBN)

Stephen Graham Jones is the NYT bestselling author of novels, collections, and novellas including Don't Fear the Reaper, Earthdivers, and The Only Good Indians. His essay 'My Life with Conan the Barbarian' reveals his love for the character. He has won the Ray Bradbury Award, the Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award, the Stoker Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the Independent Publishers Award for Multicultural Fiction. Stephen lives and teaches in Boulder, Colorado.

The Absolution of Three-Persons March 31, 1912

HE WAS THERE again today, the Indian gentleman.

This is only his second Sunday to attend, but in a congregation as tight knit as mine, I find a face I don’t know out in the chapel to be . . . not worrisome, I should think of it as a gift, as another chance to fulfill a missionary’s duty, and thereby inch myself that much closer to redemption. But his presence is disconcerting—through no fault of the Indian’s own. It’s as if he’s a face from either the past or my past, it’s hard to decide which he might unintentionally represent.

Through the whole of my sermon, I longed to lob a pebble to his isolated pew at the back, to see if he would snatch that pebble from the air at the last moment, and then hold it in his lap for the rest of the service, worrying it between his fingers. And I would follow that pebble’s journey further as well, to see if he let it fall alongside his right leg as he exited. Or maybe I would even follow him to wherever he’s found or made lodging, to see if he examines that pebble by firelight, and perhaps slips it into the medicine pouch all of his breed carry on their person, close to their skin.

I would like to have that between us, I think. I would like to be part of the secret totem beneath his shirt, held close and important to his chest forevermore.

As for this Indian’s appearance, well, he’s Indian. The red skin, the broad face and wide nose, the hatchet cheekbones, that grim slash of a downturned mouth. A distinct amusement to his eyes about our proceedings in this house of worship, but a harsh, embattled cast to his face as well, speaking of many trials and tribulations, much hardship and loss. His hair is long and oily and black, suggesting he’s not a product of Jesuit school, which is in contrast to the floor length black clerical robe he wears, about whose provenance I won’t even hazard a guess, as it may involve some Man of the Cloth’s remains moldering in a gulch.

As for his intention with arraying himself in this raiment, I have to think it’s easily explainable. Surely, in wanting to come to a white man’s church, this Indian gentleman thought it vital to attire himself after the same fashion he has to have seen white men going to church in. A failure to understand the hierarchy in these church walls, where the man behind the pulpit and he alone dresses suchly, is beneath having to excuse. Instead, I take this mimicry as the highest honor, and I’m thankful for the childlike innocence with which it’s delivered—let the little children come to me, yes.

However, that robe is the only thing childlike about this Indian. While it’s difficult to hypothesize the age of someone whose kind I’m not intimately associated with, I would put this gentlemen between his early thirties or late forties—well past the age where he would have been part of a raiding party in decades past, when such things were yet occurring, but, at the same time, he’s perhaps older than individuals of his race usually make it to. I detect no silver in his hair as of yet, but I also know that the grey comes late among his people.

And, it’s beneath saying, but the Indian’s face is cleaned to shining, beardless and not mustachioed, and his hair, though long and heavy, is drawn back, which I take as a token of respect, as when a cur pastes its ears back along its skull in hopes of passing without drawing a kick or harsh word.

This is as well as I can draw him in the pages of this newest volume of my phrenic peregrinations. His bearing and posture this Sunday was the same as last, I should add—shoulders square, spine straight. I was initially discomfited with how his eyes tracked my every movement, as if I were one of his wags-his-tails, which I understand is his people’s word for “deer,” though of the big eared variety or the smaller variety with that white flag of a tail, I can’t yet ascertain. But of course, his watching me like a deer he would roast on a spit actually makes perfect sense. Presumably familiar with enough English to accomplish simple commerce, he must be mystified by the Vater tongue I deliver my sermons with. His attentiveness, therefore, is but evidence of the concentration he trains on my words.

When everyone else reached for one of our few hymnals, he plucked one up as well, a strange flower to him, not understanding that the tome he held before him for the singing portion of the service was in fact a Bible—more evidence of his lack of formal education. Rather, he was surely educated in the Edenic hinterlands, where he can read the fowl and the fauna more closely than I can the very Scripture.

More interesting than his looks or comportment, though, are his reasons for attending my service. Is he hoping to suspend a delicate bridge from his people to mine, and so foster a unity where there’s only been decades of division? Did he, in his youth, see a wagon train assembled before a Man of the Cloth, and wonder about the power wielded by that man at the front of the congregation? Has he heard tell of the white man’s religion, and wants to see where it might line up with his inborn one?

Now that we’ve shared private and extended discussion over things so fabulous as to themselves be fables, I can speak better as to his reasoning, his reasons, but, reciting my service that first and this Sunday, I confess to having been mainly agitated about whether or not he was only here for a meal. If so, he would have had to make do with a thin white wafer. I’m ashamed to say that, during the Eucharist, I positioned myself so as to observe him. But, both Sundays, he limited himself to but a single wafer, glaring against his dark skin, that hand rising to his mouth and then coming back down, his eyes holding mine the entire time, as if to prove to me that the holy sacrament wouldn’t smoke on his pagan tongue.

I would have allowed him more and of more substantialness, of course, had he but asked or made his hunger known. Had he stayed after that first service, I would have led him to my parsonage and broken bread with him—not Mrs. Grandlin’s, that wasn’t to me yet. But, had he been there upon its arrival, then we surely would have shared in that repast. I may be gluttonous in private, but in fellowship, I hope to set a better example.

When I would have extended such fellowship to him last Sunday, however, he stood with the rest of the congregation, holding my eyes across the congregants’ as yet hatless heads, and I felt for all the world as if he had been there to judge me. Were I speaking to myself as I speak to my parishioners, I might portend that those who fear the presence of a judge may very well be carrying a secret burden of guilt they hope to unload. Yet, to be judged by an Indian, here in the new century? To have this twentieth century called to task by its predecessor?

Your fantasies know no limit, do they, old man? Leave anyone too long alone with his own thoughts, and every possibility will be not only explored, but poked and prodded until it raises its shaggy head, settles its lidless eyes on you. Such is the price of isolation, and that mulling that never ceases. Though of a different order, I feel I’m nevertheless a monk in his bare cell, with only a quill and scroll to converse with.

After this afternoon’s proceedings, I suppose I now have this Indian to converse with as well, if I’m willing to lean in closely enough to hear his subdued voice.

But I was documenting his first appearance last week, which I neglected to write about that Sunday, I think due to my dim hope that he was but an aberration in my weekly routine, not worthy of committing ink to.

And even still I explore the fullness of language and distraction in the recounting, instead of daring to look directly at this Indian. But my ink pot is full, this candle is as yet tall, my back doesn’t hurt too much yet, my nerves seem intent on continuing to twitch this nib across these evenly lined pages, and no one is immediately waiting for me to save their soul, so, what harm can there be? “Soldier on, Pastorbrotherman,” the men on the porch at the lodging house might urge me.

It’s to them I ascribe blame for the chalice of communion wine half in and half out of this candlelight. But, better it not turn to vinegar. That would be the actual pity.

This Indian, however, whom I know I need to find the strength to look directly at, at least on this unblinking page.

That first Sunday of his attendance, upon the service’s conclusion, the Spirit moving through the congregation in a way that always fills my chest, he rose with a quickness that aged him down a full decade. Though when I would have forded the bodies to hold his brown hands in mine and look meaningfully into his eyes, he turned neatly away, lowering his face into the peculiar darkened spectacles I’ve seen travelers on the train platform wearing, to look directly into the endlessly bright sky.

He did look back once, confirming the pursuit he seemed to expect, his wildborne instinct keenly aware of such things, but by the time I reached the back of the chapel in my limping manner, this Indian gentleman was striding away into the daylight, his Jesuit robe swinging around his long, purposeful strides, his hands tucked into the cuff opposite themselves, the dogs of Sunday morning giving him wide berth, which is the first time I’ve seen such a phenomenon in my time in Miles City. But surely it’s the bear grease in his hair that forces them to keep their distance, or the scent of tragedy on his skin, or that he was keeping to the shaded side of the street, where the warmth isn’t. Or...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.4.2025 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Horror |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | blood-sucking • Dark Fantasy • dark fantasy book • dark fantasy books • dark fantasy horror • dark fantasy novel • Dark Fantasy Novels • historical horror • historical horror novel • Historical horror novels • indigenous authors • indigenous fiction • Indigenous Horror • indigenous writers • Native American authors • native american fantasy • Native American horror • Native American writers • Postcolonial horror • Postcolonial horror book • Postcolonial horror books • Postcolonial horror novel • Postcolonial horror novels • Vampire • vampire book • vampire books • vampire novel • vampire novels • vampires |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83541-432-X / 183541432X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83541-432-3 / 9781835414323 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich