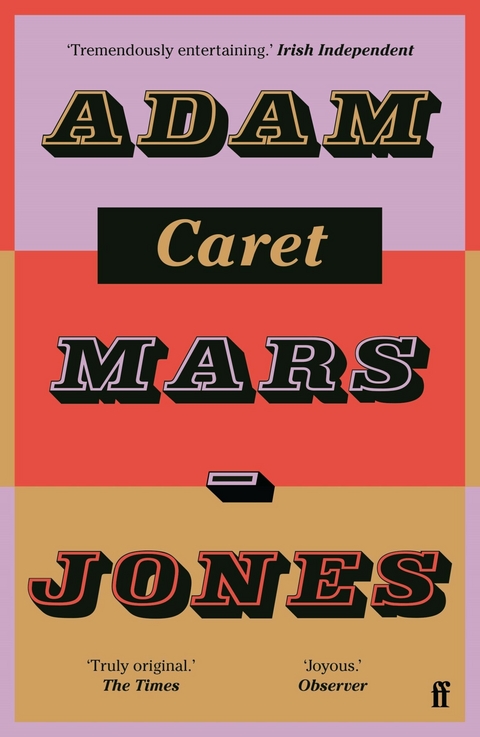

Caret (eBook)

800 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-28007-0 (ISBN)

Adam Mars-Jones's first book of stories, Lantern Lecture, was published in 1981 and won a Somerset Maugham Award. In 1983 and again in 1993 he was named one of Granta's Best of Young British Novelists, despite not having produced a novel at the time. His Zen status as an acclaimed novelist without a novel was dented by the appearance of The Waters of Thirst, and can only suffer further with the appearance of Pilcrow, described by Margaret Drabble as 'one of the most remarkable novels I have read in recent years.'

'Joyous.' Observer'Tremendously entertaining.' Irish Times'Truly original.' The Times** A Times and Guardian Book of the Year **'We make lazy assumptions about the centre of things and its location. Who's to say that the centre of things isn't in a corner, way over there?''Nobody can be a person twenty-fours hours a day - it just can't be done. At night the sets dissolve and the performance falls away. We're off the books.'That's John Cromer talking, in this fresh instalment of his lifelong saga. For John, embarking on a new stage of life in 1970s Cambridge, charm and wit aren't just assets, they are survival skills. It may be a case of John against the world. If so, don't be in too much of a hurry to bet on the world. Conjuring a remarkable voice and mind, Caret is a feast of a novel, served on a succession of small plates, each portion providing an adult's daily intake of literary nourishment. Reading it - like any encounter with John Cromer -- is guaranteed to help you work, rest and play. 'Thank god for John Cromer and his creator Adam Mars-Jones, one of the funniest, most self-aware characters in English fiction, whose minute observations on everything from constipation to lust are a source of unexpected delight.' Linda Grant

The lycopene is present in cooked tomatoes only, not in the raw fruit. This peculiarity, even before it was generally known, gave tomato ketchup a bumptious eminence on the kitchen shelf and the school menu, as if it had knowledge somehow of its own super-condimentary status. The bottle squares its non-existent shoulders and looks down on its neighbour, brown sauce harbouring no nutritional secret weapon.

‘Oh for heaven’s sake!’ came the same rich voice that had overruled my thrifty breakfast order, but this time its owner swept into view (the owner I suppose of the business also) and grabbed the dispenser. She was plump, though well-shaped, and wore a polka-dot dress. She uncapped the nozzle and held the masquerading fruit in the palm of her hand, bouncing it up and down as if getting ready for the shot-put. ‘Stripes or swirls?’ she asked.

‘Free expression,’ I said. ‘Free choice.’ I was interested to see what shapes she would produce with the viscous fluid in its lurid container. Thixotropic isn’t a word I use lightly, and may not even be the most accurate way of characterising the behaviour of extruded ketchup, but it’s still true that anyone who has a grasp of the processes at work in that nozzle is well on the way to understanding the physical world. She narrowed her eyes and then delivered an even spiral of red starting on the outside of the plate and working in. The final flourish, accompanied by a rather unfortunate farting noise, was a jet aimed directly at the yellow of one of the fried eggs, forceful enough to rupture the yolk. ‘Sorry, no money back,’ she said, ‘but then breakfast is my treat. Oh, Hettie? Take that mug away. It’s no use to him. Bring him tea in one of my cups.’

She sat down opposite me and lit a cigarette. Smokers took their rights for granted in those days, and even faculty libraries at the University had tables designated for the free exercise of self-destructive vice. ‘I’m not making you cough, am I?’ she asked breezily. ‘Not at all,’ I said, ‘I was coughing anyway.’ She would have to do a lot worse before I scolded a benefactor. I have a soft spot for buxom, bosomy ladies, I’d say motherly types except that there’s so little overlap with actual Mum, who was, as she said (without regret), ‘straight up and down’.

The teacup steaming in front of me was an improvement on the vast mug it replaced, but not by much. The ideal vessel is actually a small mug, since I control the tilting action with a couple of fingers wedged through the handle but balance the mug itself on the back of my knuckles. With an unfamiliar cup or mug, particularly when it’s full, there can be an uncertain moment as it travels towards my mouth. Then I must prehensilise my lips, thrusting them forward in an attempt to create an effective seal rather than let liquid spill. It’s hard to give an impression of any great intelligence while executing this chimps’-tea-party manœuvre. I can feel as if I’m wearing a nappy and being fed from a bottle for the amusement of jaded zoo visitors with no actual interest in wildlife.

I squared up to the teacup relatively successfully, then with a little embarrassment started to ply my imported cutlery. The lady’s eyes were slightly screwed up against the drift of her own smoke, but she managed to raise an eyebrow and called out, for the benefit of staff or anyone else in earshot, ‘Fair play to him, this one isn’t a stealer. He might even leave us a teaspoon as a tip. My name’s Whyvonne, by the way.’

‘Whyvonne with a W?’

‘Whyvonne with a Why.’

‘John.’ John with a baffled look.

‘Pleasta meetcha.’ Definitely invoking some sort of Hollywood musical I hadn’t seen. My cinematic range of reference was not wide. Yes, I’d seen a few musicals over the years, but the films that had made most impact on me during my time as an undergraduate were Wild Strawberries and El Topo.

Yvonne, Y-vonne, or even Whyvonne, smoked while I ate and kept an eye on me, as if she wanted to make sure every scrap was hitting the metabolic bullseye. She matched me mouthful for mouthful, making the smoke she swallowed keep pace with the fry-up on my plate. The alternative possible spellings of her name flickered unstably in the peripheral vision of my mind’s eye like the beginnings of a proofreader’s migraine. I was grateful that she didn’t make conversation, having too much respect perhaps for the mysterious processes that unlock the energy in food and make it available. It’s hard enough to co-ordinate the rhythms of breathing and eating without complicating the equation with talking. There’s only one mammal that can choke on its food, and that’s us, the reason being the evolutionary changes in the layout of our throats that conspire to make speech possible. To talk while eating is to play Russian roulette at table, with your œsophagus as the gun.

She wanted to see me fully fed now, in the present tense, while she watched me and talked in my direction. There was to be no tucking of bacon into pockets for later. She had obviously enjoyed establishing an ascendancy over her underling by anticipating my dilemmas with the giant tomato and the giant mug. Such little breakthroughs often send people crashing into my orbit.

She leaned forward to inspect my face, in a friendly way though the effect was still disconcerting. She said, ‘I think you’ve been bitten, darling.’

‘Bitten?’

‘You’re coming up in red bumps.’ She produced a powder compact with a stylised black daisy embossed on it and used the mirror inside to show me what she meant. I was really more interested in the design, which used five overlapping discs to represent petals, though a daisy with five petals would be a poor thing, with a thin white ring vaguely hinting at a carpel. We complain about Chinese written characters not resembling the things they are supposed to illustrate, don’t we – that’s never a horse! – but we ourselves are capable of a thousand acts of oblique decipherment a day. This shape on a plastic compact certainly said ‘daisy’ to young female shoppers, though not in the language of flowers, hardly that.

‘You see what I mean, darling?’

‘I see what you mean. Coming up in red bumps.’ The little disembodied whines Maya had sent out in the night weren’t as disembodied as all that. They had borrowed the bodies of mosquitoes. I shouldn’t have been surprised, since the stagnant water of Hobson’s Conduit lay just the other side of the railings from where the Mini was parked. By leaving the window on the driver’s side slightly open I had advertised my deliciousness, sending out appetising John smells to lure members of the family Culicidæ over the glass threshold for their feast. And I know the ligature on Culicidæ is wrong in this Linnæan context but I can’t help myself. To my way of thinking vowels are balls of ice cream in a bowl and will always half melt into each other if given the chance.

Somewhere Nietzsche says a clever thing about mosquitoes and their consciousness, but as usual I can’t remember if it was wise or only got as far as clever and stopped short.

‘When you’ve finished your breakfast, darling, I’ll see if I can find some TCP.’ I’d never really liked TCP, partly because of the smell and partly because they changed the formula sometime in my childhood, and I’m a bit of a traditionalist in such matters. Meanwhile Whyvonne bent down and picked up a large black cat with white markings, holding it on its back in her lap. It was certainly long-suffering. She swung it about as if it was no more than a scarf or a shawl. Perhaps she cultivated the habit of disconcerting her customers, though Mum had always done the same sort of thing, with cats and even with birds, wearing them as accessories in a way that compensated for her lack of interest in clothes.

The cat under the woman’s stroking, searching, manipulating hands, their nails thickly coated with red polish, seemed absent in some definite way, though cats of course rather specialise in abstention from the attention they have demanded. He let himself be dandled rather fatalistically, and I wondered whether this unusual cat would even have the energy to make a landing, if she happened to drop him.

‘He’s not been well,’ she said, in a tone of voice that would have been suitable in a bulletin about a member of the royal family. ‘You’ll never guess what brought him down.’

I was well stuck in on the second egg, the one with its yellow membrane intact. ‘A bad batch of catnip?’ I coughed, not surprisingly, since I was now, against my preferences, requiring my mouth to handle breathing, eating and talking duties simultaneously. The apparatus was overwhelmed.

She made a face. ‘I’m serious.’

‘Don’t know.’

‘Antifreeze.’

Antifreeze?

‘Antifreeze. It must taste good, or at least it must taste sweet. He came back from a prowl and could...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.8.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-28007-2 / 0571280072 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-28007-0 / 9780571280070 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich