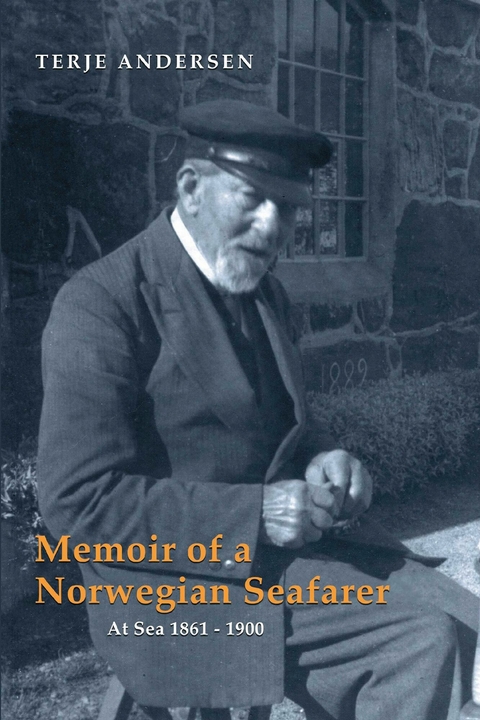

Memoir of a Norwegian Seafarer (eBook)

268 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-8055-6 (ISBN)

Introduction

This book tells the story of Captain Terje Andersen, 1846 to 1940, and chronicles in a personal and reflective way the rise and subsequent fall of a great maritime culture on the South Coast of Norway. To fully appreciate the story, we need to put Terje Andersen and his time into perspective.

Terje Andersen grew up in the small seaside village of Narestø, some 15 kilometers east of Arendal, a town which at that time was the wealthiest in Norway and had the country’s largest fleet of sailing ships. Narestø and the parish of Flosta were characterized by the bustling culture of sailing and seafaring, where going to sea at the age of 14 appeared the obvious choice for most young boys.

The village of Narestø is situated at the western tip of the Flosterøy island in an archipelago stretching from Arendal to Lyngør. At the top of the island, the 15th Century Flosta church sits with a grand view of the coastline and the ocean beyond. The church was built largely through gifts from seafarers and must have been an important meeting place during Terje Andersen’s time; in fact, he would become a churchwarden later in life.

The parish of Flosta was by nature and social relations split into three parts. The eastern island of Tverdalsøya, and in particular the hamlet of Bota, was largely intertwined with the islands to the east: Borøya, Sandøya, Askerøya and Lyngør in the neighboring parish of Dypvåg. Then there were the “mainland” communities of Vatnebu, Eikeland and Borås; just as focused on seafaring as the others. Finally the village of Narestø at the western end of Flosterøya was more connected to Arendal in the west.

The harbor at Arendal, 15 kilometers from Terje Andersen’s hometown of Narestø. Photograph is courtesy of the Kuben Museum in Arendal.

White sails and a wide horizon

The South Coast of Norway at this time represented something of a paradox: It was remote and sparsely populated, yet it was bordering the busiest sea lane of the 19th Century: the Skagerrak Strait and the rest of the seaway between the Baltic Sea and Western Europe.

From the hilltops, where the local pilots kept watch on approaching vessels, one could easily discern the white spots of sails passing on the horizon, vessels on their way from the Baltic laden with timber. White sails and the wide horizon offered a constant allure for the young.

During the autumn gales, the pilots would keep a constant lookout for ships in distress, driven by wind and current toward the lee shore and the treacherous coast. Almost every year there would be shipwrecks, but also damaged vessels seeking refuge behind the outer islands and sometimes staying over the winter in places like Narestø. And as autumn came, the locally-owned vessels would return for winter lay-up, while aspiring youngsters attended classes in navigation to qualify for the navigation certification and a mate’s position.

Of the three Scandinavian countries, Norway had the most obvious exposure to the sea with its long coastline stretching from Skagerrak — between southeastern Norway and Sweden -- up Norway’s western and northern coasts all the way to the Russian border.

The area around Oslo fjord and along the South Coast would prosper from the timber trade, as timber was brought down to the coast by the rivers and exported to Britain and the European Continent. This also generated activity and prosperity locally in Flosta, with farmers trading across Skagerrak to Denmark with small vessels. Although trade and shipping were the privilege of the town merchants, the rural population in the county of Nedenes had long enjoyed a royal privilege to trade with the farmers of Jutland, the Danish peninsula separating the North Atlantic and Baltic seas. In time, the seafaring spirit got the better of the rural dwellers, and they began trading further afield, shipping timber in larger vessels.

The archipelago stretching from Arendal towards Lyngør, comprising the Flosta and Dypvåg parishes, emerged during the 18th Century as one of the first dedicated “shipping communities” — seafaring with cargo as a business in itself, not just a means of trade. Strong connections were established in Britain, particularly with merchants in Faversham in Kent. It was not uncommon for a Norwegian captain to leave his son as a trainee with his merchant friend in Britain over the winter.

By the year 1806, in Dypvåg and Flosta the leading shipowners came together to establish the first mutual marine insurance institution in Norway, Oxefiordens Gjensidige Sjøassuraceforening, or the Oksefjord Mutual Sea Insurance Association.

In 1807, the “Dual Monarchy” of Denmark-Norway1 found itself at war with Britain, as part of the Napoleonic Wars wherein England, Ireland and Russia were fighting French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. The British Navy attacked Copenhagen and Danish and Norwegian ships, hoping to keep them out of the hands of Napoleon. Denmark-Norway had tried to remain neutral, but joined Bonaparte’s side after the attack. Sweden, meanwhile, was allied with the British. The parish of Flosta at the time had a fleet of 15 sailing ships mostly employed in the timber trade to Britain.

The conflict, known as the Gunboat War, ended with a peace settlement in Kiel in January 1814 that represented a defeat for the Danish, who ceded Norway to Sweden. In Norway, the Danish prince Christian Fredrik was elected king and the constitution of an independent nation was signed on May 17, 1814. Norwegians had to accept the Swedish king as sovereign, but retained their own constitution and were free to run their own country.

The first decade after the Napoleonic war found independent Norway in a precarious position. The export of timber now met with trade barriers in Britain, and the merchant fleet suffered. It was only through the union with Sweden that Norwegian vessels from 1827 on were permitted to carry timber from Swedish ports to Britain. But then the tide turned, and the shipping business gradually picked up, with British reform bills in the 1840s and particularly the repeal of the Navigation Act in 1850 paving the way for free trade and open seas.

The greatest adventure

In the village of Narestø our protagonist, Terje Andersen, would hardly have been aware of the profound change that happened in 1850 when he was a little boy of four. Yet his father and the wealthier shipowners in the village would certainly have heard the great news: Norwegian ships -– and in fact ships of every nationality -– would now be able to take cargos to British ports or even make voyages between the British colonies.

Sailing ships in the 1800’s were often built on harbors in small coastal towns. This ship, Jona, was built along the harbor in Hisøy. The photograph was provided by Hisøy Historielag to the Kuben Museum in Arendal.

The British free trade movement would soon inspire a change of policy in most of the Western world, coinciding with progress in education, public enlightenment, the gradual adoption of democracy and a technological revolution with steamships, railways and telegraphs opening the world in an entirely new manner. This would lead to a sharp rise in trade and commerce, what historians often refer to as “The First Globalization,” with world trade doubling by 1875.

The grand political shift would also affect far-off Norway. Free access to the shipping markets opened opportunities, and the scale of shipbuilding and new investment saw Norway emerge as the third largest maritime nation by 1875; after Great Britain and the USA, but ahead of Germany, France and Canada. This was almost entirely with a fleet of wooden sailing vessels, largely built, financed and manned locally. It was a true adventure, and Flosta and the village of Narestø were at its heart.

By 1850 there were some 1,000 inhabitants in the parish of Flosta, with eight sailing ships owned locally. Twenty-five years later the local fleet consisted of 46 ships employing 400 to 450 seafarers. Almost all men in the community relied on the maritime professions. The parish, like the district at large, saw the population grow by 70 percent by 1890.

Flosta was a thriving and busy community with a social structure of wealthy families of shipowners and captains, often doubling as small farmers, a few traders and craftsmen, and hardly a family without one or more husbands and sons away at sea. Places like Sundsvall, Cardiff, Pensacola and Buenos Aires were household names.

Ship in early stage of production in the small town of Grimstad, a few kilometers from Narestø. Photograph courtesy of the Kuben Museum.

But how could it all be possible? Capital for financing the ships? Shipbuilding skills? The entrepreneurship to take on repairs and careening?2 Financial means were organized through partnerships; every vessel owned by a separate partnership often through family and kinship. The captain was required to have a share. Ownership was fragmented, but as long as shipping was profitable, putting your savings into a vessel seemed a sensible thing to do. The cost of a vessel had to be subscribed in full; generally in cash but occasionally in kind, such as delivery of timber or iron fittings.

Change and decline

By the mid-1880s, the sailing...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.4.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-8055-1 / 1667880551 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-8055-6 / 9781667880556 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 12,3 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich