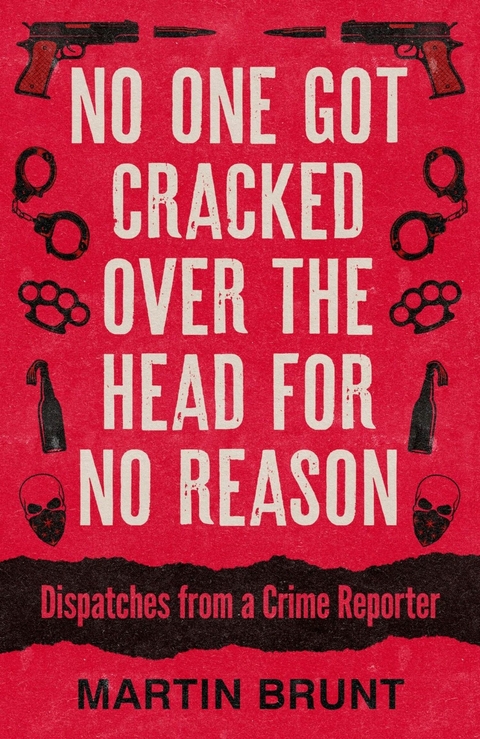

No One Got Cracked Over the Head for No Reason (eBook)

336 Seiten

Biteback Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-78590-779-1 (ISBN)

Martin Brunt is crime correspondent for Sky News. He has been with the channel since its launch in 1989, spending the first five years as a general reporter before moving to his now-familiar role covering stories from grisly murders to bank heists. He lives in the south of England.

"e;A cracking tale"e; - Duncan Campbell, investigative journalist and author of Underworld"e;A revelation"e; Professor Sue Black, author of All That Remains and Written in Bone"e;Required reading for professional and amateur criminologists"e; Gerald Seymour, bestselling author of Harry's Game"e;Highly recommended"e; Howard Sounes, author of Fred & Rose"e;A gripping read"e; Patricia Wiltshire, author of Traces: The memoir of a forensic scientist and criminal investigator"e;This book is a must-read"e; David Wilson, Professor Emeritus of Criminology***What is it about crime that we find so fascinating, even if at the same time the details are repugnant? Why exactly do we immerse ourselves in true crime podcasts and TV shows? Has this appetite for gore shifted over the years? And what role does the crime reporter play in all of this?In this compelling book, Martin Brunt draws on the most shocking and harrowing stories he's covered over the past thirty years to document the life of a crime reporter and assess the public obsession with crime that his reporting caters for. He also considers the wider relationship between the press and the police, the impact of social media and the question of why some crimes are ignored while others grip the nation. Featuring many undisclosed details on some of the biggest cases Brunt has covered, from the 'Diamond Wheezers' to Fred and Rose West, this blend of storytelling and analysis is not only a riveting overview of the nature of crime reporting but a reflection on the purpose of the profession in the first place.

Well, I didn’t say: ‘Darling, I’m just off to stick up Barclays.’ I told her I was going out to do a bit of work and see you later

– Retired gangster Freddie Foreman

Not every day of a crime reporter’s life is filled with such horror. And sitting in a pub, sipping beer with a friendly detective, isn’t something I do a lot. But it’s not a bad way to earn a living. Some reporters do still enjoy a regular boozy lunch with their contacts, especially those who work for newspapers where we developed bad habits in secret drinking dens that were open all day long before pubs were allowed extended hours.

When I joined Sky News after a dozen years as a newspaper hack, I soon discovered that alcohol and live television don’t mix, although TV producers have since seized on the cocktail as a vital ingredient of prurient reality shows, where contestants are encouraged to have sex in front of the cameras. I like to think that news, for now at least, is a rather more serious business, though I’ve had my light-hearted and much-ridiculed moments on screen, and not all of them were intentional.

My world changed when newspaper reporters at the Sunday tabloid News of the World discovered a simple way of hacking into the mobile phones of royal aides, celebrities and politicians and finding out what they were up to. Scotland Yard’s initial, half-hearted pursuit of the journalists – and the hacking of a murdered schoolgirl’s phone – prompted a high-profile police investigation, more official scrutiny and the closure of Britain’s best-selling newspaper. That all culminated in the Leveson judicial inquiry into the media’s relationship with police and politicians. There was always going to be only one loser. The job of being a crime reporter, whether on TV, newspapers or the internet, changed for ever.

Leveson effectively brought an end to the way in which reporters got exclusive stories from their police contacts. Sir Brian Leveson, a senior judge, acknowledged the media had a vital role in certain functions, but he didn’t believe that some journalists should be given special access to information held by a public body such as the police service. From then on, he said, police should record all contact with journalists.

If he’d known about it, Leveson would have frowned on my pub meeting with DI O’Reilly to discuss the Thames torso case. The judge wrote in his report: ‘If a police officer tips off a member of the press, the perception may well be that he or she has done so in exchange for past favours or the expectation of some future benefit.’

There was no such edge to my meeting with the detective. All O’Reilly wanted was help in solving a troubling murder. Maybe that was the future benefit Leveson meant, but what was wrong with that? The police wouldn’t bother talking to journalists at all if they didn’t believe there would be some kind of benefit, which in most cases is the public’s help in solving a crime. Surely, catching criminals is to the public’s benefit, isn’t it?

O’Reilly had retired by the time of the Leveson Report – he’d been promoted to chief inspector but hadn’t solved the torso case – but plenty of my contacts were still investigating major crimes, and after Leveson my calls and texts to them went largely unanswered. I got used to seeing them only at press conferences, where we were spoon fed limited information about current cases and given little chance to probe behind the official version. At least my bar bills went down.

If my job has become harder, it’s even tougher now to be a villain and get away with it, though recent Home Office revelations of falling crime detection rates suggested a temporary shift in the balance between good and evil. The increasingly detailed analysis of DNA, mobile phone tracking, the spread of CCTV, new money-laundering laws, the growth of home-security and car-dashboard cameras, the use of drones and the development of facial and vehicle recognition technology: all have been added to police capability in the war on crime. And law enforcers are always looking for new ideas.

A detective involved in a complicated corruption case once complained to me, over a coffee near my Westminster office, that his suspects were too clever to be caught out by listening devices hidden in their phones and cars. He asked if my employers at Sky would put a bug inside a suspect’s satellite TV system. It would involve our technical department creating a ‘fault’ and then sending round a technician to ‘correct it’. I passed on the request, but I already knew the answer would be a firm no and not even a polite one.

Criminals, like the rest of us, use the latest communications systems. It’s almost impossible for them to avoid leaving a digital footprint that can provide prosecution evidence as damning as a fingerprint. Some villains do fight back in the technology war, with cheap, disposable and unregistered ‘burner’ mobile phones bought for cash, encrypted messaging systems and all sorts of signal blockers and jammers. But a lot of villains still don’t get it and think gloves and a balaclava will prevent them being identified.

I asked the Flying Squad commander Peter Spindler how the ageing Hatton Garden heist gang – the ‘diamond wheezers’ as a Sun headline brilliantly put it – were caught, so soon after they escaped with their £14 million loot. He summed it up succinctly: ‘They were analogue villains operating in a digital world.’ Among the gang’s stupid mistakes: the getaway driver used his own car, another bought a drill and gave his home address, and they failed to turn off a security camera. In court the key evidence against them was digital data from their mobile phones, their computers and CCTV, rather than old-fashioned witnesses.

I’ve interviewed many criminals because it’s interesting to hear their stories. I’m not sure it sheds much light on their motives, which are usually greed and idleness or, as I heard a lawyer describe it rather poetically: ‘The prospect of dishonest gain almost beyond the dreams of avarice.’

I asked Freddie Foreman, once one of Britain’s most-feared gangsters and a figure much respected in the underworld, what he told his wife when he left home to commit an armed robbery. ‘Well, I didn’t say: “Darling, I’m just off to stick up Barclays.” I told her I was going out to do a bit of work and see you later.’ How much later Mrs Foreman saw Fred rather depended on the success of the robbery.

On my grim beat, many of the characters I encounter are as seemingly humdrum as the rest of us but sometimes, by their actions and ambitions, the most captivating individuals. They can hold your attention rapt and at the same time send a shiver down your spine. At a sunny beach cafe beside the Adriatic Sea, Italian gangster Valerio Viccei had me gripped with tales of his £60 million diamond heist.

Viccei was educated, charming and articulate, not your everyday robber with his traditional lifestyle of ‘birds, booze and betting.’ I knew my audience would be thrilled by a glimpse into a world forbidden to most of them, imagining perhaps what they might do with just one of the ten Fabergé eggs he stole. My own fascination with Viccei dipped a bit when he threatened to kill me.

These are some of the characters in this book, along with the stories behind the stories, which are often more interesting than the headline-grabbing crimes themselves. Sometimes they’re quite bizarre. In a Spanish jail, conman Mark Acklom asked me if Sky would pay his €30,000 bail money. Before you ask, we didn’t.

Tales like that break up the monotony of the day-to-day crime stories we get from the police. Membership of the Crime Reporters’ Association gives us access to special background briefings by detectives but, since Leveson, they don’t happen as often as they did. We used to have monthly gatherings in the press room at Scotland Yard, the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police in London, with the commissioner. In theory at least, nothing was off-limits, and we could expect a candid response to a probing question.

We got most out of those meetings when Sir John Stevens – now Lord Stevens – was commissioner. He was a tall, imposing figure who was forthright in his views, understood the media and knew a good headline. One day, his officers were accused of overreacting during a pro-fox-hunting demonstration outside Parliament. This wasn’t your average rally, but a gathering of largely conservative, land-owning individuals, many dressed in waxed Barbour coats, whose natural instincts were to support the police. The explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes and the TV cook Clarissa Dickson Wright were among the posh protestors.

The demonstration had started peacefully enough but turned angry. Before long police had drawn their batons and were exchanging blows with a section of the crowd. Bottles were thrown and some officers had their helmets knocked...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.4.2025 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Politik / Gesellschaft | |

| Schlagworte | crime reporting • Journalism • Leveson inquiry • sky news • True Crime |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78590-779-4 / 1785907794 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78590-779-1 / 9781785907791 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich